Impact Factor

ISSN: 1449-1907

Int J Med Sci 2026; 23(3):889-915. doi:10.7150/ijms.125066 This issue Cite

Research Paper

Integrin αvβ3 is a Potential Therapeutic Target in Cholangiocarcinoma

1. Graduate Institute of Cancer Molecular Biology and Drug Discovery, College of Medical Science and Technology, Taipei Medical University, Taipei 11031, Taiwan.

2. Department of Surgery, Division of Neurosurgery, Shuang Ho Hospital, Taipei Medical University, New Taipei City, Taiwan.

3. TMU Research Center of Cancer Translational Medicine, Taipei Medical University, Taipei 11031, Taiwan.

4. Department of Immunology and Microbial Disease, Albany Medical College, Albany, NY 12208, USA.

5. Department of Pediatrics, E-DA Hospital, I-Shou University, Kaohsiung 82445, Taiwan.

6. School of Medicine, college of Medicine, I-Shou University, Kaohsiung 82445, Taiwan.

7. Department of Radiation Oncology, Shuang Ho Hospital, Taipei Medical University, New Taipei City, Taiwan.

8. Graduate Institute of Clinical Medicine, College of Medicine, Taipei Medical University, Taipei, Taiwan.

9. Faculty of Applied Sciences and Biotechnology, Shoolini University of Biotechnology and Management Sciences, Himachal Pradesh, 173229, India.

10. Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Internal Medicine, Wan Fang Hospital, Taipei Medical University, Taipei 116, Taiwan.

11. Department of Internal Medicine, School of Medicine, College of Medicine, Taipei Medical University, Taipei 110, Taiwan.

12. Joint Biobank, Office of Human Research, Taipei Medical University, Taipei, Taiwan.

13. Graduate Institute of Metabolism and Obesity Sciences, College of Nutrition, Taipei Medical University, Taipei 11031, Taiwan.

14. Graduate Institute of Nanomedicine and Medical Engineering, College of Medical Engineering, Taipei Medical University, Taipei 11031, Taiwan.

15. Faculty of Chemistry, University of Science, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam.

16. Vietnam National University, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam.

17. Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Cell Biology, Taipei Medical University, Taipei, 110, Taiwan.

18. Faculty of Pharmacy, Van Lang University, 69/68 Dang Thuy Tram Street, Ward 13, Binh Thanh District, Ho Chi Minh City 70000, Vietnam.

19. Yogananda School of AI Computers and Data Sciences, Shoolini University, Solan 173229, India.

20. Cancer Center, Wan Fang Hospital, Taipei Medical University, Taipei 11031, Taiwan.

21. Traditional Herbal Medicine Research Center of Taipei Medical University Hospital, Taipei Medical University, Taipei 11031, Taiwan.

22. TMU Research Center of Cancer Translational Medicine and Lung Cancer Research Team, Taipei Medical University, Taipei 11031, Taiwan.

# These authors contributed equally to this work.

Received 2025-9-11; Accepted 2026-1-5; Published 2026-2-4

Abstract

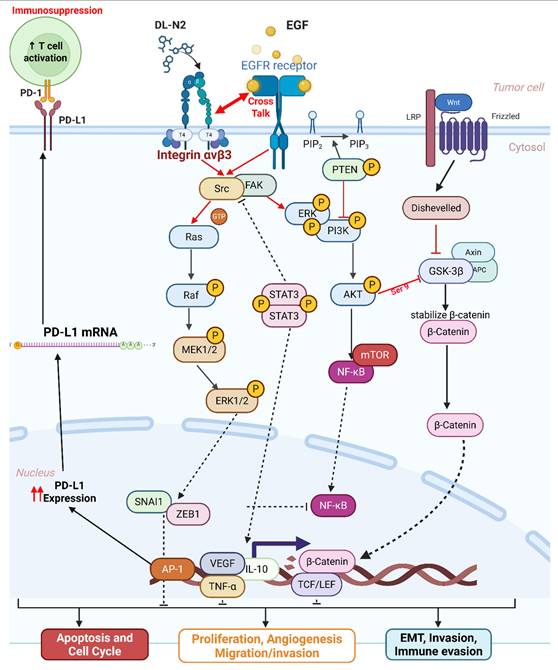

Cell surface receptors play vital roles in cancer growth and metastasis. Integrin αvβ3 is overexpressed in various cancer cells and interacts with different growth factors to stimulate cancer progression. Thyroid hormone binds to αvβ3 to activate signal transduction and cell proliferation. However, thyroxine (T4) deaminated analogue, tetraiodothyronine (tetrac), competes for the binding on integrin and inhibits cancer cell growth and metastasis. The current study investigated the pathogenic role of integrin αvβ3 and the potential of a novel therapeutic strategy targeted to integrin αvβ3. Pathogenetic studies of clinical samples revealed integrin αvβ3 cross-talked with EGFR and downstream signal transduction networks affected by thyroid hormone and EGF related to the progression of cholangiocarcinoma malignancy. Thyroxine and EGF stimulated PD-Ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression and cancer growth in cholangiocarcinoma. The thyroxine-induced PD-L1 accumulated in the nuclei and colocalized with p300. Alternatively, EGF increased cytosolic PD-L1 and nuclear accumulation of β-catenin. Targeting integrin αvβ3 with lipo-tetrac and its Dox-derivative induced anti-proliferation in vitro and in the xenografted animal model. Our research provides a fundamental understanding of the therapeutic role of integrin αvβ3 and the potential therapeutic approach in cholangiocarcinoma treatment.

Keywords: integrin αvβ3, epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1), thyroxine, epidermal growth factor, nano-tetrac, cholangiocarcinoma

Introduction

Cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) is a highly aggressive malignancy arising from the biliary tract epithelium and has become increasingly recognized worldwide for its poor clinical outcome. CCA accounts for about 3 percent of all gastrointestinal cancers and 10-20 percent of primary liver cancer [1, 2]. The incidence of cholangiocarcinoma has been rising globally, with the highest rates observed in Southeast Asia, where the disease often results from chronic infection with Opisthorchis viverrini and Clonorchis sinensis, parasites known to cause biliary tract inflammation [3]. However, in Western countries, the disease is mainly associated with primary sclerosing cholangitis, hepatitis B and C virus infections, and liver cirrhosis [3, 4]. Clinically, CCA is classified into three anatomical subtypes: intrahepatic (iCCA), perihilar (pCCA), and distal (dCCA). Perihilar tumors are the most common, representing 50-60 percent of all cases, followed by distal CCA at 20-30 percent and intrahepatic CCA at roughly 10 percent [5, 6]. These subtypes differ in their cell of origin, stromal architecture, immune composition, and dominant signaling pathways, which has important implications for biomarker expression and therapeutic targeting [7]. Despite advances in imaging techniques and surgical approaches, cholangiocarcinoma is typically diagnosed at an advanced stage when surgical resection is no longer feasible. The prognosis remains poor, with a 5-year survival rate of less than 10% for patients diagnosed with advanced disease and high rates of recurrence [1, 8]. The lack of effective targeted therapies and the resistance to chemotherapy further complicate treatment outcomes.

Integrins such as integrin αvβ3 are increasingly recognized as critical molecules in tumor progression. Integrin αvβ3 is a cell surface receptor involved in cell adhesion, migration, and invasion [9]. It mediates interactions between cells and the extracellular matrix, facilitating tumor cell attachment and migration. Integrin αvβ3 has been implicated in tumor metastasis, and its expression correlates with poor prognosis in various cancers [10]. In cholangiocarcinoma, integrin αvβ3 has been shown to contribute to the invasion and migration of cancer cells, enhancing the potential for metastasis [11]. The thyroid hormone signaling pathway has a wide range of functions in terms of individual development, maintenance of homeostasis, cell proliferation and differentiation, and glucose metabolism. In addition to thyroid nuclear receptor, triiodothyronine (T3) and L-thyroxine (T4) can bind to integrin αvβ3 and stimulate cancer cell growth and metastasis [12]. It shows the relevant functions of various cancers by stimulating the extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2) pathways responsible for tumorigenesis [12].

In addition to integrin αvβ3, EGFR (epidermal growth factor receptor) is a key player in the progression of cholangiocarcinoma. This receptor tyrosine kinase is overexpressed in various cancers, including cholangiocarcinoma [13]. EGFR regulates numerous cellular processes, including cell proliferation, survival, migration, and invasion, by activating downstream signaling pathways such as RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK, PI3K/AKT, and JAK/STAT [14]. EGFR activation plays a crucial role in driving tumor progression by promoting cell division and survival, and its inhibition has been shown to reduce tumor growth and metastasis in preclinical models [15]. In cholangiocarcinoma, EGFR overexpression has been associated with poor prognosis, and targeting EGFR has emerged as a potential therapeutic strategy [16]. Moreover, integrins have been shown to cooperate with EGFR in promoting tumor progression and immune modulation. It has been well-established that thyroxine stimulates EGFR-dependent signal transduction via integrin αvβ3 [12], suggesting that targeting both molecules simultaneously could provide a more effective therapeutic strategy [11].

Recent studies have highlighted the importance of immune evasion mechanisms in the progression of many cancers, including cholangiocarcinoma. Immune checkpoint molecules, such as PD-L1 (programmed death-ligand 1), have gained significant attention due to their enabling tumors to evade immune surveillance. PD-L1 expression is upregulated in many cancers, including cholangiocarcinoma [17-19]. It plays a pivotal role in immune suppression by binding to its receptor PD-1 on T cells. This interaction leads to T cell exhaustion, a potentially permanent dysfunction characterized by reduced or absent T cell effector function, lack of response to stimuli, and altered transcriptional and epigenetic state [19]. However, the molecular factors regulating PD-L1 expression in cholangiocarcinoma remain poorly understood, making it an important target for further investigation.

One of the hallmarks of cholangiocarcinoma is its ability to evade the immune system, a phenomenon known as immune escape [20]. Tumor cells often exploit various immune checkpoint pathways to suppress the body's natural immune response. The interaction between EGFR, integrins, and PD-L1 is particularly interesting, as these molecules may work together to modulate both the tumor microenvironment and the immune landscape [21]. EGFR activation can induce PD-L1 expression in tumor cells, while integrins may contribute to immune cell recruitment and immune suppression [21, 22]. The exact mechanisms by which EGFR and integrin αvβ3 regulate PD-L1 expression and immune cell infiltration in cholangiocarcinoma remain unclear, and understanding these interactions is of utmost importance for developing targeted therapies to overcome immune evasion. Given the aggressive nature of this disease, developing novel therapeutic strategies targeting the underlying molecular mechanisms is crucial [1, 8]. However, the interplay between EGFR and other molecular markers, such as PD-L1, and their combined impact on immune modulation in cholangiocarcinoma remains unclear.

Crosstalk between signal transduction pathways has been well-described in cancer pathology. It has also developed combination therapies to block different signal transduction pathways. Recently, we have shown that targeting integrin αvβ3 by 3 3' 5 5'-tetraiodothyroacetic acid and its nano-particulate derivatives (NDAT) can inhibit cancer growth in vitro and in vivo in EGFR-mutant cancer cell lines [12]. Modulating integrin αvβ3-dependent signal transduction by nano-tetrac suppresses activations of PI3K, ERK1/2, and PD-L1 expression sequentially. Consequently, nano-tetrac inhibits cancer proliferation in vitro and in vivo [12].

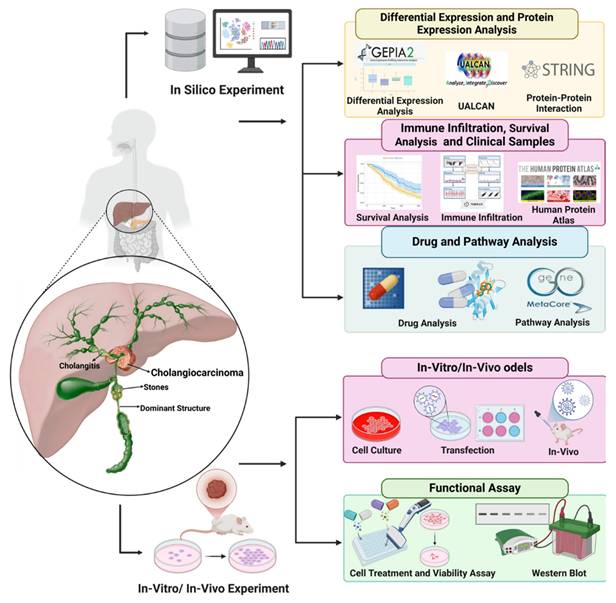

In this study, we aimed to analyze the pathogenic role of integrin αvβ3 and its correlations with EGFR and PD-L1 in cholangiocarcinoma. Combining bioinformatic analysis, cell line experiments, and clinical biopsy validation, we validated the integrin αvβ3 antagonist, nano-tetrac derivative-induced anti-proliferation in cholangiocarcinoma xenograft modeling. The flowchart of our study, as illustrated in Fig. 1, represents a significant step forward in our understanding of cholangiocarcinoma. We aimed to understand how integrin αvβ3 and EGFR regulate PD-L1 expression and immune modulation in cholangiocarcinoma to identify new therapeutic strategies that target these molecular pathways. By bridging bioinformatic insights with experimental validation, our findings may provide new avenues for targeted therapies that can significantly improve the prognosis of cholangiocarcinoma patients. We also validated the hypothesis of the stimulating effect of thyroid hormone and EGF in cholangiocarcinoma, providing reassurance about the reliability of our findings. Finally, we verified the anti-cancer growth of nano-tetrac derivatives effectively in xenograft modeling, further underlining the potential impact of our study.

Materials and Methods

Cell Cultures

Human bile duct carcinoma TFK-1 was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Gaithersburg and Germantown, MD). KRAS wild-type SSP-25 and KRAS mutant HuCCT1 were obtained from Riken Bioresource Research Center (Tsukuba, Japan) and were authenticated by a next-generation sequencing (NGS) analysis. Based on the NGS analysis, results indicated that the intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, SSP-25 cell is ETK-1:TP53; Simple; p.Arg175His (c.524G>A), which correlated with the results shown on the website. Cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 at 37 ºC.

DL-N2 and Integrin αvβ3 Binding Characteristics

DL-N2 is a nanoparticulate formulation of tetraiodothyroacetic acid (tetrac) designed to target the thyroid hormone receptor site on integrin αvβ3. Structural and biochemical studies show that this receptor pocket is formed at the interface between the αv S1 domain and the β3 I-like domain, indicating that effective binding requires the intact αvβ3 heterodimer. DL-N2 does not interact with αv or β3 individually. Functional loss-of-activity experiments further demonstrate that β3 plays the dominant role in transmitting tetrac-dependent inhibitory signaling, whereas αv knockdown produces only a partial reduction in response. Through this interaction, DL-N2 blocks T4-mediated activation of FAK/SRC, PI3K, ERK1/2, and STAT3 pathways, thereby suppressing integrin-dependent tumor growth and enhancing the effects of EGFR-targeted therapy [23-25].

Bioinformatic Analysis

Bioinformatic analysis was carried out to investigate the expression and correlation of key genes in cholangiocarcinoma using publicly available datasets. Bioinformatics tools such as GEPIA2 and UALCAN were used to perform differential expression analysis, survival analysis, and clinical relevance studies [26, 27]. GEPIA2 is a comprehensive web tool for analyzing gene expression across various types of cancer using RNA-seq data. We utilized this tool to analyze the differential expression of integrin αvβ3, EGFR, and PD-L1 in different cancer types, specifically focusing on cholangiocarcinoma. The tools allow for the visualization of gene expression data and comparing expression patterns between tumor and normal tissues. UALCAN is another powerful bioinformatic tool that we used for clinical analysis. It integrates large-scale cancer data to study the expression of genes in various cancer types. We specifically employed UALCAN to assess the relationship between EGFR, integrin αvβ3, and PD-L1 expression in cholangiocarcinoma and their relevance to patient survival. STRING databases were used to explore the interactions between EGFR, PD-L1, and integrin αvβ3 for protein-protein interaction (PPI) network analysis [28]. STRING allowed us to visualize the interactions between these genes and identify potential signaling pathways involved in cholangiocarcinoma progression. In addition to the interaction analysis, we used Metacore, Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis to investigate the biological functions and signaling pathways associated with EGFR and integrin αvβ3 [29].

Single-cell RNA-seq data for cholangiocarcinoma was analyzed using the publicly available dataset GSE142784, which was downloaded as a pre-processed and annotated object from the TISCH2 portal [30]. The dataset contained curated major and minor cell-type labels, including malignant status, fibroblast subtypes, endothelial cells, immune subsets, and myeloid lineages. The expression matrix and metadata were imported into Seurat (v5.0) for downstream analysis [31]. Following log-normalization, highly variable genes were identified using the default selection method. Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed, and the first 20 principal components were used to compute the shared nearest neighbor graph. Uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) was then carried out to generate two-dimensional embeddings and cluster separations. Cell clustering was conducted using the standard Seurat workflow with the default resolution parameter, after which the original TISCH2 annotations were mapped back onto the Seurat-generated clusters to ensure biological consistency.

Schematic diagram depicting the experimental workflow employed in this study to investigate cholangiocarcinoma and its molecular mechanisms. The schematic diagram illustrates the integrated in silico, in vitro, and in vivo approaches used in this study. Computational analyses were conducted to examine differential gene expression, protein interactions, immune infiltration, and survival correlations using tools such as GEPIA2, UALCAN, STRING, and the Human Protein Atlas. Drug sensitivity, molecular docking, and pathway analysis were performed using GDSC2 and MetaCore to explore potential therapeutic targets. In vitro experiments included cell culture, transfection, and functional assays, such as cell viability and Western blot analysis, to validate computational findings and investigate key molecular mechanisms in cholangiocarcinoma.

To examine gene-level expression patterns, feature plots and violin plots were generated for ITGAV, ITGB3, EGFR, and CD274, enabling visualization of their distribution across malignant, stromal, and immune populations. For intercellular communication analysis, the annotated Seurat object was converted for use in CellChat (v1.6), and ligand-receptor modeling was performed using the built-in human interaction database. Signaling probabilities, interaction strengths, and compartment-level communication patterns were computed using the default parameters. All plots, including UMAP projections, violin plots, and communication networks, were generated using the SingleCellPipeline (SCP) package, which provided unified visualization formatting and ensured reproducible figure generation.

Cell Viability Assay

SSP-25 and HuCCT1 cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a 3000 cells/well density. After 24 h for cell attachment, cells were starved with 0.25% hormone-depleted serum-supplemented medium for 24 h. Then, serum-starved cells were treated with various concentrations of EGF (cat. no.: E9644, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), or T4 (cat. no.: SI-T2376, Sigma-Aldrich) at varying concentrations and treatment times according to the experimental design. Cells that did not receive EGF or T4 were treated with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or KOH-PG buffer, respectively. Medium and reagents were refreshed daily. Cell viability was assayed with an alamar blue Cell Viability Reagent (cat. no.: DAL1025, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Western Blotting

SSP-25 and HuCCT1 cells were seeded in 6 cm petri dishes. Cells were starved with 0.25% hormone-depleted serum-supplemented medium for 24 h. Cells were treated with different agents for 24 h before harvest. After cells were harvested, proteins were extracted according to the research design. Protein samples were resolved by 10% sodium dodecyl-sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). A 10 μg quantity of protein was loaded into each well with sample buffer, and samples were resolved by electrophoresis at 100 V for 2 h. The resolved proteins were transferred from the polyacrylamide gel to Millipore Immobilon-PSQ Transfer polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) with the Mini Trans-Blot® Cell (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Membranes were blocked with a solution of 2% bovine serum albumin in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) with 0.1% Tween-20 (TBST) and incubated with primary antibodies to PD-L1 (cat. no.: GTX104763, GeneTex International, Hsinchu City, Taiwan) at a 1:1000 dilution, AKT (cat. no.: 60203, Proteintech) at a 1:1000 dilution, p-AKT (Ser473) (cat. no.: 9271, Cell Signaling Technology) at a 1:1000 dilution, STAT3 (cat. no.: 610190, BD Biosciences) at a 1:1000 dilution, p-STAT3 (Tyr705) (cat. no.: 9145, Cell Signaling Technology) at a 1:1000 dilution, p-STAT3 (Ser727) (cat. no.: 9136, Cell Signaling Technology) at a 1:1000 dilution, non-p-β-catenin (Ser33/Ser37/Tyr41) (cat. no.: 8814, Cell Signaling Technology) at a 1:1000 dilution, p-β-catenin (Ser33/Ser37/Tyr41) (cat. no.: 9561, Cell Signaling Technology) at a 1:1000 dilution, β-catenin (cat. no.: 610153, BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA, USA) at a 1:1000 dilution, lamin B1 (cat. no.: GTX103292, GeneTex International) at a 1:1000 dilution, and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (cat. no.: 60004-1, GeneTex International) at a 1:10,000 dilution at 4 °C overnight. The antibody-probed membrane was washed with TBST containing 5% fat-free milk (5% TBST/milk) three times for 10 min and then probed with goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) (cat no.: GTX213111-05, GeneTex International) or goat anti-rabbit IgG (cat. no.: GTX213110-04, GeneTex International) horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies, which were prepared in 5% TBST/milk at a 1:10,000 dilution at room temperature for 1 h. After the membrane was washed three times for 10 min with TBS, chemiluminescent detection was performed using the Immobilon Western Chemiluminescent HRP Substrate (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). Bands were imaged with the BioSpectrum Imaging System (UVP, Upland, CA, USA) and quantified using densitometry by ImageJ 1.47 software (National Institute of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA) according to the software instructions.

Animal Study Design

All animal experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the National Defense Medical Center, Taipei, Taiwan (IACUC, LAC-2020-0471). 6-week-old NOD SCID mice were purchased from the National Laboratory Animal Center (Taipei, Taiwan), housed in a reserved, pathogen-free facility and acclimated to the nursery for one week before the experiment. For xenograft implantation, mice were anesthetized with 3 % isoflurane and subcutaneously inoculated with aliquots of 1 × 107 TFK-1 cells/100 μl 50 % Matrigel (BD Matrigel™ Basement Membrane Matrix). Seven days post-implantation, the tumor status was assessed, and the mice were randomly divided into distinct experimental groups. After two weeks, when the tumor grew bigger than 100 mm3, mice received intravenous injections of either solvent (PBS), DL-N2 (tetrac 0.1 mg/kg), Lipo-Dox (Dox 2 mg/kg), or DL-N2-Dox (tetrac 0.1 mg/kg and Dox 2 mg/kg) by one dose per week for four weeks. The tumor sizes will be measured every three days by caliper and calculated by formula V = (d× D × L)/2. The change in tumor volume was calculated by dividing the final measured volume by the initial measured volume. After four weeks of treatment, all animals were sacrificed, the tumor weight was measured and analyzed.

Statistical Analysis

In this study, the statistical significance of all data was analyzed by a two-tailed Student's t-test using Excel. All data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) or standard error of the mean (SEM). p < 0.05 (*), and p < 0.01 (**) were considered statistically significant.

Results

Bioinformatic Analyses Reveal Integrin αvβ3-EGFR-PD-L1 Axis in Cholangiocarcinoma

Targeting integrin αvβ3 with thyroxine deaminated analogues or its nano-particulate can inhibit cancer growth in vitro and in vivo. They also induced anti-cancer growth in KRAS mutant EGFR antagonist gefitinib-resistant cancer cell lines [32]. These observations raised our interest in investigating the key role of integrin αvβ3 in cholangiocarcinoma and its correlations with EGFR in pathogenic effects in cholangiocarcinoma. To comprehensively explore the molecular dynamics of integrin αvβ3 in cholangiocarcinoma, we began with bioinformatic studies that integrated various publicly available cancer datasets. The central focus of this study was the analysis of integrin αvβ3 and its network, especially EGFR. They are key surface biomarkers implicated in cancer progression and metastasis. Integrin αvβ3 is a critical molecule involved in cell adhesion, migration, and extracellular matrix interactions, facilitating tumor invasion in various types of cancer. On the other hand, EGFR is well-known for its role in cell signaling pathways, such as ERK, AKT, and PI3K, which are crucial for tumor survival and proliferation. Furthermore, studies demonstrate that integrin αvβ3 crosstalks with EGFR for cancer progression.

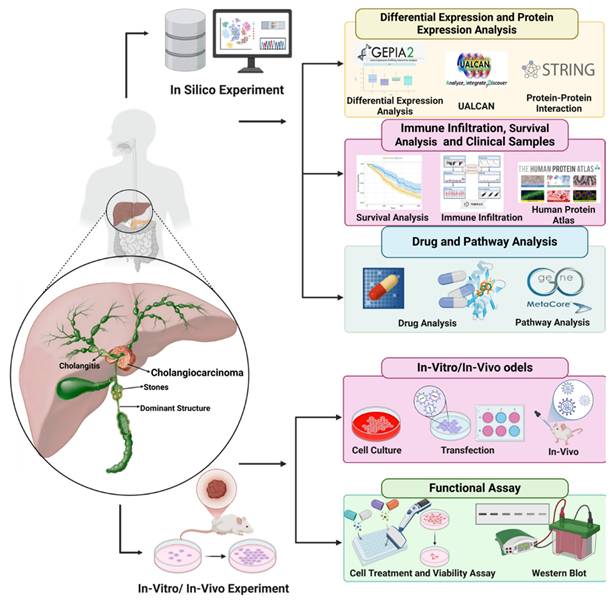

To elucidate the oncogenic and immunomodulatory landscape of cholangiocarcinoma (CHOL), we conducted a series of bioinformatic analyses focusing on integrin αvβ3 (comprising ITGAV and ITGB3), EGFR, and PD-L1 (CD274). Differential gene expression analysis from publicly available datasets revealed that ITGAV, ITGB3, EGFR, and PD-L1 were all significantly upregulated in CHOL tumor tissues compared to normal bile duct tissues (Fig. 2A-D). ITGAV expression was markedly higher in tumors, aligning with its established role in facilitating extracellular matrix interactions and tumor invasion (Fig. 2A). ITGB3 expression was notably elevated (Fig. 2B). In parallel, EGFR, a known driver of cell proliferation and survival, also showed strong upregulation (Fig. 2C), highlighting its involvement in promoting tumor cell adhesion and metastasis. Furthermore, the immune checkpoint molecule PD-L1 was significantly overexpressed (Fig. 2D), indicating the potential for immune escape mechanisms in CHOL.

Correlational analysis revealed significant positive associations between ITGAV, ITGB3, EGFR, and PD-L1 expression levels (Fig. 2E). For example, ITGAV expression correlated with both EGFR (r = 0.31) and PD-L1 (r = 0.31). ITGB3 also showed modest correlations with EGFR (r = 0.28) and PD-L1 (r = 0.27). These findings suggest that these molecules may operate in a coordinated network contributing to CHOL pathogenesis. The co-expression and pathway convergence underscore the potential of targeting the integrin αvβ3-EGFR-PD-L1 axis as a therapeutic strategy in cholangiocarcinoma. To further understand the functional implications of these molecular alterations, we performed Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) on samples with high expression of the above markers. The analyses showed robust enrichment of the IL6/JAK/STAT3 signaling and IFN-γ response pathways (Fig. 2F-I), which are known to contribute to tumor immune modulation and inflammation. Notably, STAT3 activation has been linked to the transcriptional regulation of PD-L1, suggesting a possible mechanistic link among integrin signaling, EGFR activation, and immune checkpoint expression.

Moreover, PD-L1, a well-known immune checkpoint molecule, was also highly expressed in cholangiocarcinoma samples, correlating with the tumor's potential to evade immune detection. ITGAV expression shows differential expression, with increased levels in specific cancers like breast and gastric cancer. ITGB3 also follows a similar pattern, indicating its involvement in tumor progression and metastasis. EGFR expression is significantly higher in various cancers, with prominent upregulation observed in tumors such as lung and colon cancers [33]. However, PD-L1 expression is notably elevated across multiple tumor types, suggesting its role in immune escape mechanisms [34]. These initial findings underscore the importance of integrin αvβ3, EGFR, and PD-L1 as key players in the pathogenesis of cholangiocarcinoma. The upregulation of these molecules in cholangiocarcinoma supports their role in immune evasion and suggests that targeting them could be a promising therapeutic strategy.

Correlation between Integrin αvβ3 Expression and Key Genes in Cholangiocarcinoma

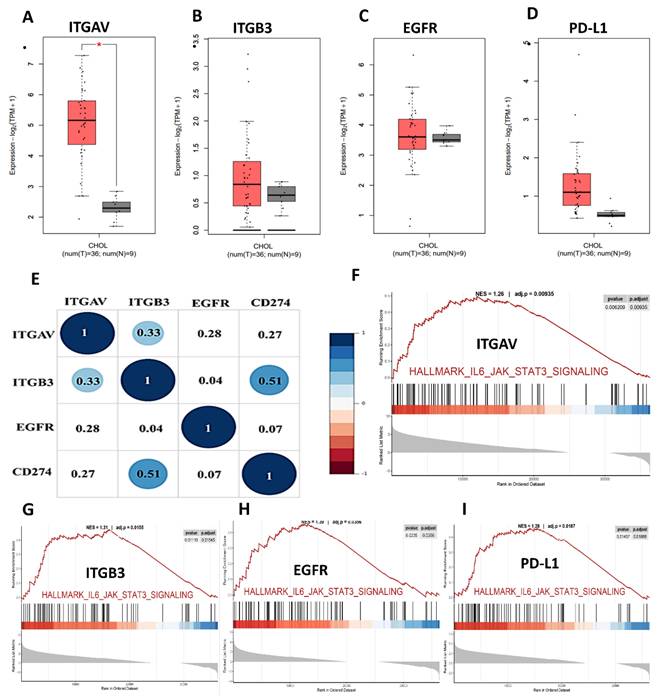

To explore the relationship between integrin αvβ3 (composed of ITGAV and ITGB3) and other key genes implicated in cholangiocarcinoma, we performed both correlation analysis and protein-protein interaction (PPI) network mapping (Fig. 3). The PPI network (Fig. 3A) revealed extensive interactions among integrin subunits (ITGAV and ITGB3), EGFR, CD274 (PD-L1), and major signaling molecules such as AKT1, SRC, STAT3, MAPK1, and MAPK3. Notably, EGFR emerged as a central hub in the network, displaying strong associations with ITGAV, ITGB3, and PD-L1. This suggests that EGFR may coordinate tumor-promoting signaling events such as cell adhesion, migration, and immune evasion. The STRING interaction confidence scores (Fig. 3B) further confirmed these associations, with particularly high scores for ITGAV-ITGB3 (0.999), ITGB3-SRC (0.998), ITGB3-MAPK1 (0.728), and CD274-EGFR (0.87), highlighting their potential co-regulatory roles in cholangiocarcinoma pathogenesis.

Expression and pathway analysis of ITGAV, ITGB3, EGFR, and PD-L1 in cholangiocarcinoma (CHOL). (A-D) Box plots showing gene expression levels (log₂ TPM + 1) of ITGAV, ITGB3, EGFR, and PD-L1 in CHOL tumor tissues (T, n = 36) versus normal tissues (N, n = 9) from TCGA data. Tumor samples show significantly elevated expression compared to normal controls, with statistical significance denoted by asterisks (*p < 0.05). (E) Correlation matrix (circle plot) displaying positive correlations among ITGAV, ITGB3, CD274 (PD-L1), and EGFR, highlighting potential co-expression and coordinated regulation in cholangiocarcinoma pathogenesis. (F-I) Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) plots showing enrichment of the IL6-JAK-STAT3 signaling pathway in samples with high expression of the respective genes, indicating their involvement in inflammatory and tumor-promoting pathways.

Integrated correlation and interaction analysis of ITGAV, ITGB3, EGFR, and CD274 (PD-L1) in cholangiocarcinoma. (A) Protein-protein interaction (PPI) network constructed using the STRING database, depicting the interactions among key genes: ITGAV, ITGB3, EGFR, CD274, SRC, STAT3, MAPK1, MAPK3, and AKT1. Edge colors represent known or predicted interactions, highlighting the central role of EGFR and CD274 in immune regulation and oncogenic signaling. (B) Tabulated STRING correlation scores between select gene pairs, showing strong co-associations such as ITGAV-ITGB3 (0.999), ITGB3-SRC (0.998), and CD274-EGFR (0.87), suggesting functional interplay in CHOL progression. (C-E) Expression correlation scatter plots between CD274 (PD-L1) and ITGAV (C), ITGB3 (D), and EGFR (E) in cholangiocarcinoma (TCGA dataset). All three genes show significant positive correlations with CD274: ITGAV (cor = 0.413, p = 1.29e-02), ITGB3 (cor = 0.532, p = 1e-03), and EGFR (cor = 0.462, p = 4.96e-03), supporting potential co-regulation and immune checkpoint association.

We next examined whether these protein-level interactions are mirrored at the transcriptional level. Correlation analysis of gene expression (Fig. 3C-E) revealed that ITGAV expression positively correlated with PD-L1 (CD274) (R = 0.413, p = 1.29e-02; Fig. 3C), suggesting a potential link between integrin signaling and immune checkpoint regulation. Similarly, ITGB3 expression was significantly correlated with PD-L1 (R = 0.532, p = 1.00e-03; Fig. 3D), reinforcing the idea that integrin αvβ3 may influence immune evasion. A strong positive correlation was also observed between ITGAV and ITGB3 (R = 0.615, p = 9.19e-05), indicating coordinated expression of these integrin subunits. EGFR expression was moderately correlated with both ITGAV (R = 0.462, p = 4.96e-03; Fig. 3E) and PD-L1 (R = 0.13, p = 0.39; non-significant), suggesting that while EGFR might not directly regulate PD-L1 transcriptionally, it could modulate immune escape through integrin-associated signaling pathways. EGFR showed no significant correlation with ITGB3 (R = 0.07, p = 0.65), indicating a more complex or context-dependent interaction between these molecules. These findings suggest that integrin αvβ3 and EGFR may synergize to promote cholangiocarcinoma progression by enhancing both migratory signaling and immune checkpoint expression. Targeting the crosstalk between these pathways could offer novel therapeutic strategies for cholangiocarcinoma.

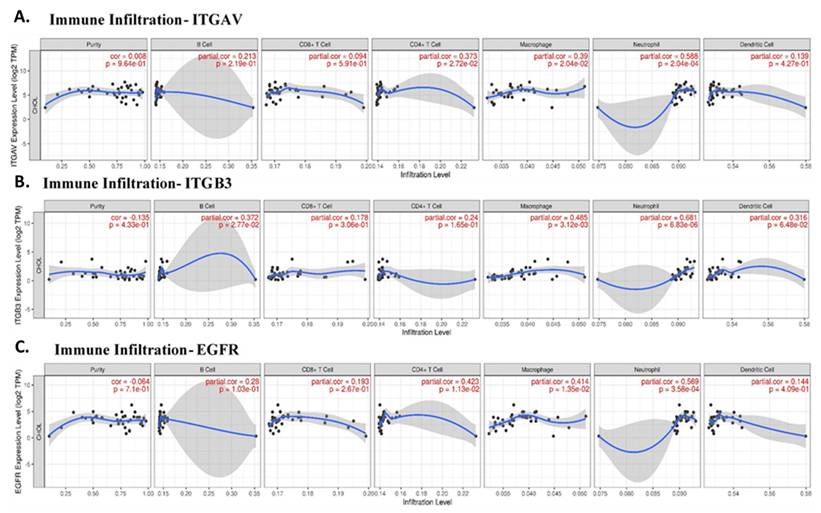

Correlation between Immune Cell Infiltration and Key Genes in Cholangiocarcinoma

Given the role of integrins and EGFR in immune modulation, we next explored the correlation between these genes and immune cell infiltration in cholangiocarcinoma. Immune cells such as neutrophils, macrophages, and CD4+ T cells are integral components of the tumor microenvironment and can either promote or inhibit tumor progression, depending on their polarization. Our analysis revealed that ITGAV expression was significantly correlated with neutrophil infiltration (partial correlation = 0.588, p = 2.04e-04), supporting the idea that ITGAV might be involved in recruiting neutrophils to the tumor site (Fig. 4A). This result consists with previous reports showing that integrins are involved in immune cell trafficking and tumor inflammation. ITGB3 was also associated with neutrophil and macrophage infiltration (Fig. 4B), suggesting that integrin signaling pathways play a vital role in shaping the immune landscape in cholangiocarcinoma. A significant correlation between EGFR expression and the infiltration of CD4+ T cells (partial correlation = 0.423, p = 1.13e-02) and neutrophils (partial correlation = 0.569, p = 3.58e-04) in cholangiocarcinoma tissues (Fig. 4C). This result suggests that integrin αvβ3 and EGFR may play a role in recruiting and activating immune cells within the tumor microenvironment, particularly, neutrophils and T cells, which are important for anti-tumor immunity. Furthermore, together, these results highlight the potential of integrin αvβ3 and EGFR as modulators of the immune response in cholangiocarcinoma. These findings are crucial for understanding the immune dynamics in cholangiocarcinoma and may help inform therapeutic strategies aimed at reprogramming the immune microenvironment.

The correlation between the expression levels of ITGAV, ITGB3, and EGFR with the infiltration levels of various immune cell types in cholangiocarcinoma. A. Illustrates the correlation between ITGAV and immune cell infiltration, revealing a significant relationship with Neutrophils (partial correlation = 0.588, p = 2.04e-04), supporting the role of ITGAV in neutrophil recruitment in cholangiocarcinoma. CD4+ T cells also exhibit a notable correlation. B. Displays the correlation of ITGB3 with immune infiltration, with significant associations with Neutrophils (partial correlation = 0.661, p = 6.83e-06) and Macrophages (partial correlation = 0.485, p = 3.12e-03), indicating a potential role of ITGB3 in immune cell recruitment and tumor progression. C. Shows the relationship between EGFR expression and immune cell infiltration, with notable neutrophils (partial correlation = 0.569, p = 3.58e-04), suggesting that EGFR expression is associated with immune cell infiltration, particularly in the context of immune modulation. B Cells and CD8+ T cells show weaker correlations. These findings suggest that EGFR, ITGAV, and ITGB3 play significant roles in modulating the immune microenvironment, particularly in relation to immune cells like neutrophils, macrophages, and CD4+ T cells, which are essential in tumor immunity.

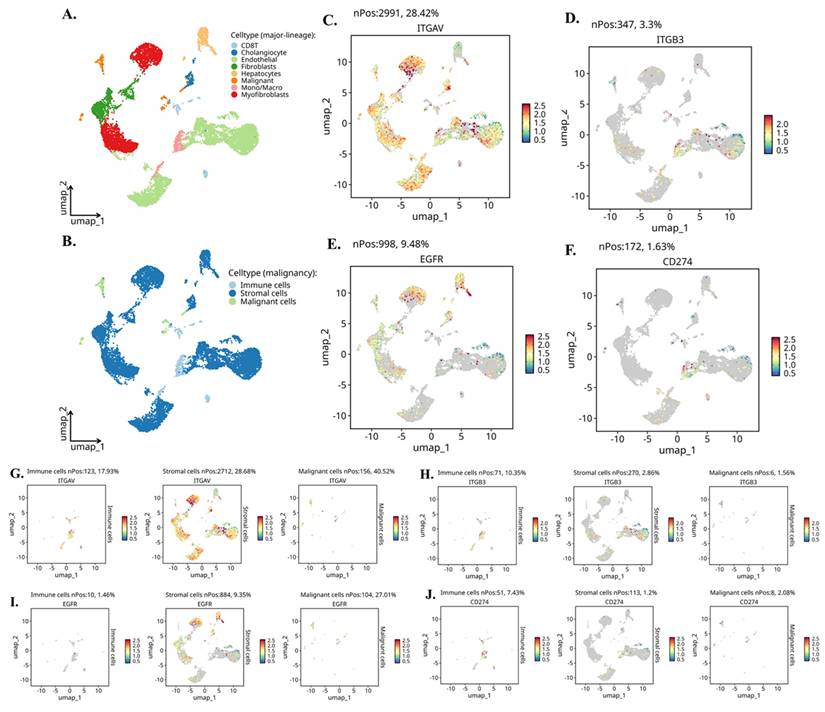

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Identifies Cell Type-Specific Expression of Integrin αvβ3, EGFR, and PD-L1 in Cholangiocarcinoma

To map the cellular sources and biological context of integrin αvβ3, EGFR, and PD-L1 expression in cholangiocarcinoma (CCA), we analyzed independent scRNA-seq dataset CHOL_GSE142784. UMAP clustering (Fig. 5A-B) clearly resolved malignant epithelial cells, non-malignant cholangiocytes, stromal fibroblasts and myofibroblasts, endothelial cells, hepatocytes, and multiple immune lineages including T cells and monocyte/macrophage populations. This provided a cellular atlas for identifying lineage-specific roles of integrin signaling and EGFR-driven pathways in the tumor microenvironment. Global gene-expression mapping revealed distinct biological functions associated with each molecule (Fig. 5C-F). ITGAV (integrin αv) showed widespread distribution across malignant, stromal, and endothelial cells (Fig. 5C), consistent with its known role as a broadly expressed adhesion receptor involved in ECM sensing, mechanotransduction, and pro-invasive remodeling. In contrast, ITGB3 (integrin β3) exhibited highly restricted expression (Fig. 5D), appearing predominantly in fibroblasts, myofibroblasts, and a subset of macrophages. This pattern aligns with the biological requirement of β3 for generating the αvβ3 heterodimer specifically within activated stromal and inflammatory niches. EGFR expression was strongly enriched in malignant cholangiocytic cells (Fig. 5E), reflecting its function as a proliferative and survival driver in CCA. CD274 (PD-L1) was primarily expressed by monocyte/macrophage populations (Fig. 5F), supporting its role in shaping immunosuppressive circuits through myeloid-driven checkpoint regulation.

Single-cell expression landscape of ITGAV, ITGB3, EGFR, and CD274 in cholangiocarcinoma. (A) UMAP projection of the single-cell dataset showing major lineage identities, including cholangiocytes, endothelial cells, fibroblasts, hepatocytes, immune cells, malignant cells, monocytes/macrophages, and myofibroblasts. (B) UMAP classification of cells by malignancy status, separating immune, stromal, and malignant populations. (C-F) Gene-level UMAPs displaying the distribution and expression intensity of ITGAV (C), ITGB3 (D), EGFR (E), and CD274 (F) across all cell populations. Expressing cells are highlighted, and non-expressing cells are shown in grey; nPos values indicate the number and percentage of positive cells. (G-J) Compartment-specific expression of each gene across immune, stromal, and malignant cells. Panels show UMAPs re-projected within each compartment for ITGAV (G), ITGB3 (H), EGFR (I), and CD274 (J), illustrating differential enrichment across distinct cellular subsets. Expression intensity is represented using a continuous color scale.

Compartment-specific reanalysis (Fig. 5G-J) further uncovered a functionally coordinated division of labor among malignant, stromal, and immune lineages. ITGAV remained most abundant in malignant epithelial cells (Fig. 5G, left), indicating that tumor cells provide the αv subunit necessary for ligand recognition and downstream FAK/Src activation. Stromal fibroblasts and myofibroblasts generated the highest levels of ITGB3 (Fig. 5H, middle), confirming that the β3 subunit originates from stromal sources and may heterodimerize with tumor-derived αv in a paracrine manner. EGFR expression was again dominant in malignant cells (Fig. 5I, right), highlighting the tumor-intrinsic reliance on EGFR-mediated mitogenic signaling. CD274 showed strong enrichment in immune cells, especially macrophages (Fig. 5J, left), indicating that the immunosuppressive PD-L1 signal is largely myeloid-driven, with minor contributions from malignant cells.

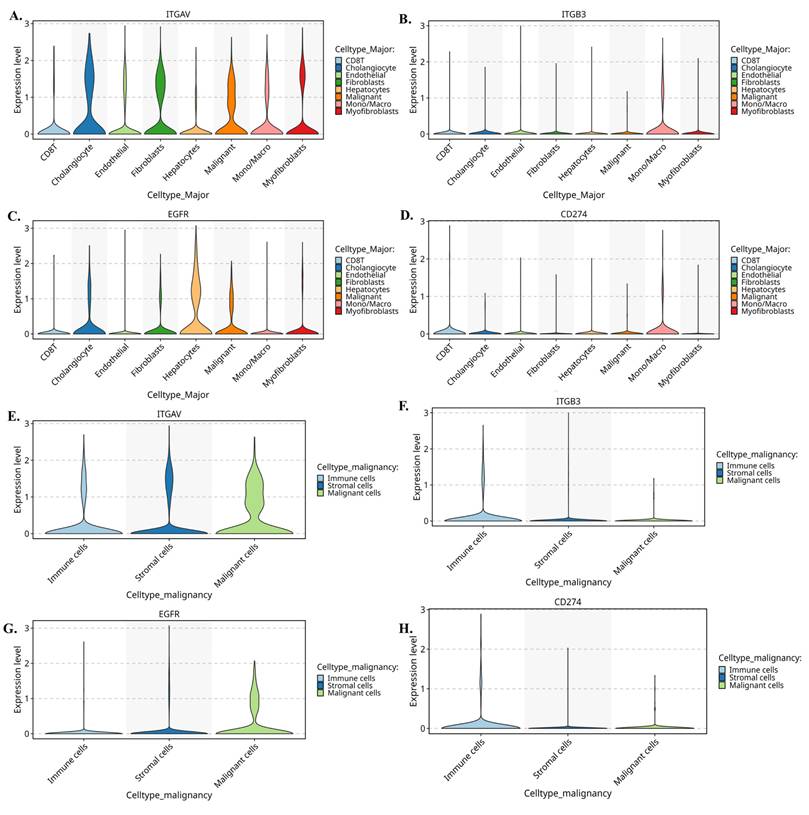

Single-cell expression patterns of ITGAV, ITGB3, EGFR, and CD274 across major cholangiocarcinoma cell populations. (A-D) Violin plots showing expression of ITGAV (A), ITGB3 (B), EGFR (C), and CD274 (D) across major cell types identified in the single-cell CCA atlas, including cholangiocytes, endothelial cells, fibroblasts, hepatocytes, macrophages/monocytes, myofibroblasts, NK/T cells, and B cells. (E-H) Violin plots comparing the expression of ITGAV (E), ITGB3 (F), EGFR (G), and CD274 (H) among malignant epithelial cells, stromal cells, and immune cells. Malignant epithelial cells show higher expression of ITGAV and EGFR, while ITGB3 is enriched in stromal and macrophage populations. CD274 is detected in both malignant and immune subsets.

Further we evaluate the violin plots (Fig. 6A-D) which quantify these patterns and further reinforce the compartmental specificity. In Figure 6A, ITGAV expression peaks in malignant epithelial cells, with moderate levels in stromal fibroblasts and endothelial cells. In Figure 6B, ITGB3 shows a striking stromal bias, being highly expressed in fibroblasts, myofibroblasts, and macrophages. Figure 6C demonstrates that EGFR is strongly enriched in malignant cells, while Figure 6D shows CD274 expression primarily in monocyte/macrophage populations. Moreover, when these cells are reorganized into malignant, stromal, and immune compartments, the distribution becomes even clearer. Figure 6E shows that ITGAV remains dominant in malignant cells, while Figure 6F confirms stromal localization of ITGB3. Figure 6G highlights malignant enrichment of EGFR, and Figure 6H demonstrates that CD274 is mainly immune-derived with modest expression in malignant cells. Together, these patterns reveal a functional division in which malignant cells supply αv and EGFR, while stromal fibroblasts and immune cells contribute β3 and PD-L1.

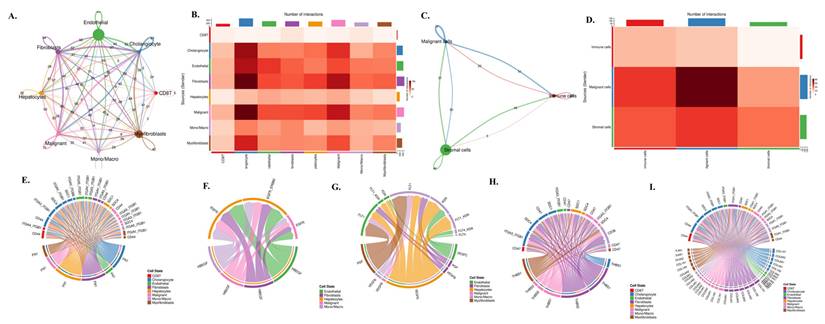

To investigate how these lineage-specific expression patterns translate into functional communication within the tumor microenvironment, we performed a comprehensive CellChat analysis (Fig. 7A-I). The global interaction network (Fig. 7A) revealed dense bidirectional signaling among nearly all cell types, with endothelial cells, fibroblasts, and malignant epithelial cells functioning as major communication hubs. Quantification of ligand-receptor pairs (Fig. 7B) showed that malignant cells receive a disproportionately high number of incoming signals, particularly from fibroblasts, myofibroblasts, and monocyte/macrophage populations. When the data were simplified into malignant, stromal, and immune compartments (Fig. 7C), stromal-to-malignant communication emerged as the dominant axis, followed by strong immune-to-malignant signaling. This was further supported by compartment-level interaction counts (Fig. 7D), where malignant cells appeared as the primary signal recipients in the tri-compartment network. To dissect the molecular nature of these interactions, we mapped specific ligand-receptor families that regulate tumo stroma immune cross-talk. ECM-integrin signaling (Fig. 7E) showed strong fibroblast- and myofibroblast-derived FN1, COL1A1, COL3A1, and THBS1 engaging integrin complexes such as ITGAV-ITGB3 and CD44 on malignant cells. EGFR-driven pathways (Fig. 7F) demonstrated that ligands including HBEGF and EREG originate mainly from endothelial and fibroblast populations, delivering mitogenic cues directly to EGFR-high malignant cells. Angiogenic circuits involving VEGFA, FLT1, and FLT4 (Fig. 7G) were primarily exchanged between malignant, stromal, and endothelial compartments, consistent with vascular remodeling in cholangiocarcinoma. Macrophage-derived SPP1 formed a dominant immunomodulatory axis by binding to ITGAV/ITGB3 and CD44 receptors on malignant and stromal cells (Fig. 7H), reinforcing tumor-supportive and immune-suppressive signaling. Finally, the integrated ligand-receptor map (Fig. 7I) combines ECM, growth factor, angiogenic, and immune pathways, illustrating the highly coordinated and multi-layered communication structure underpinning cholangiocarcinoma progression.

Taken together, these integrated single-cell and CellChat analyses reveal a highly structured and compartment-specific signaling architecture within the cholangiocarcinoma microenvironment. Malignant epithelial cells emerge as a central ITGAV-high and EGFR-high population, positioning them as the dominant recipients of proliferative, pro-survival, and ECM-driven mechanotransductive cues. In contrast, stromal fibroblasts and myofibroblasts form an ITGB3-rich niche that supplies the key β3 subunit required for assembling the functional αvβ3 integrin complex, while also producing abundant ECM ligands such as FN1, COL1A1, COL3A1, and THBS1 that activate integrin signaling on tumor cells. Meanwhile, macrophages serve as the primary source of PD-L1 and secrete SPP1, reinforcing immune suppression and potentiating integrin-dependent communication with malignant and stromal compartments. These coordinated exchanges create a directional signaling hierarchy in which stromal and immune cells continuously feed integrin-activating, EGFR-stimulating, and immune-modulating signals to malignant cells. Collectively, this framework highlights a cooperative tri-compartment ecosystem malignant, stromal, and immune that sustains tumor growth, invasion, angiogenesis, and immune evasion through tightly integrated αvβ3, EGFR, and PD-L1 signaling circuits.

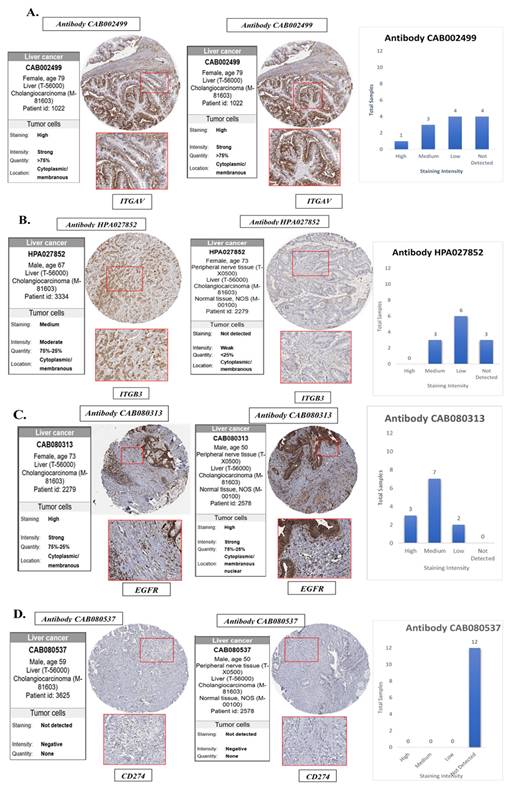

Protein-Level Validation of ITGAV, ITGB3, EGFR, and PD-L1 Expression in Cholangiocarcinoma Tissues

To validate the transcriptomic and single-cell findings at the protein level, we utilized immunohistochemistry (IHC) data from The Human Protein Atlas (HPA) to assess the expression of ITGAV, ITGB3, EGFR, and PD-L1 in cholangiocarcinoma tissues and normal bile duct controls (Fig. 8). This analysis aimed to confirm whether the elevated mRNA expression of these genes is reflected at the protein level in clinical tumor specimens, thereby strengthening their translational relevance. The IHC images revealed that ITGAV, ITGB3, and EGFR proteins were highly expressed in cholangiocarcinoma tissues compared to normal bile ducts. ITGAV showed strong membranous and cytoplasmic staining in tumor epithelial cells, consistent with its role in cell adhesion and integrin-mediated signaling. ITGB3 exhibited a similar localization pattern, reinforcing its involvement in forming the αvβ3 heterodimer and facilitating tumor invasion. EGFR was prominently expressed in the membrane and cytoplasm of malignant cholangiocytes, supporting its known function as a driver of proliferative and survival signaling in tumors. In contrast, PD-L1 (CD274) protein expression was undetectable in the cholangiocarcinoma tissues analyzed, despite its upregulation at the mRNA level in bulk and single-cell RNA sequencing data. This discrepancy suggests that PD-L1 may be regulated post-transcriptionally or its expression may be context-dependent, induced only under specific microenvironmental stimuli such as cytokine exposure or immune pressure. Alternatively, it may reflect tumor heterogeneity, where only subsets of cholangiocarcinoma cases exhibit detectable PD-L1 protein expression.

Cell-cell communication network and ligand-receptor signaling architecture in cholangiocarcinoma. (A) Global cell-cell communication network inferred from CellChat, showing the number and strength of outgoing and incoming interactions among cholangiocytes, endothelial cells, fibroblasts, hepatocytes, malignant epithelial cells, monocyte/macrophage lineages, myofibroblasts, and CD8 T cells. Node size represents overall communication strength, and edge thickness corresponds to interaction probability. (B) Heatmap summarizing the total number of ligand-receptor interactions between each pair of cell types, illustrating the dominant communication routes across the tumor microenvironment. (C) Simplified three-compartment interaction network showing signaling exchanges among malignant, stromal, and immune cells. Edge direction and thickness indicate the magnitude of outgoing and incoming signals for each compartment. (D) Heatmap of compartment-level interactions depicting the number of signals transmitted from stromal, malignant, and immune populations to one another. (E) Chord diagram illustrating ECM-integrin signaling interactions, including FN1-, COL1A1-, COL3A1-, and THBS1-mediated binding to integrin complexes such as ITGAV-ITGB3 and CD44 across multiple cell types. (F) Chord diagram of EGFR-related signaling pathways showing ligand-receptor pairs such as HBEGF-EGFR and EREG-EGFR among endothelial, fibroblast, malignant, and immune populations. (G) Chord diagram showing VEGF and FLT signaling interactions, including VEGFA-FLT1/FLT4 and related endothelial and stromal communication circuits. (H) Chord diagram mapping the SPP1-CD44 and SPP1-ITG ligand-integrin axes, highlighting macrophage-derived signaling to malignant and stromal compartments. (I) Chord diagram summarizing global ligand-receptor interactions among all cell types, integrating ECM, immune, angiogenic, and growth factor pathways within the cholangiocarcinoma microenvironment.

Collectively, these protein-level findings confirm the elevated expression of ITGAV, ITGB3, and EGFR in human cholangiocarcinoma and highlight them as robust biomarkers and potential therapeutic targets. Despite transcriptomic evidence, the absence of detectable PD-L1 protein underscores the need for integrated multi-level analyses when evaluating immune checkpoint markers in cancer (Fig. 8).

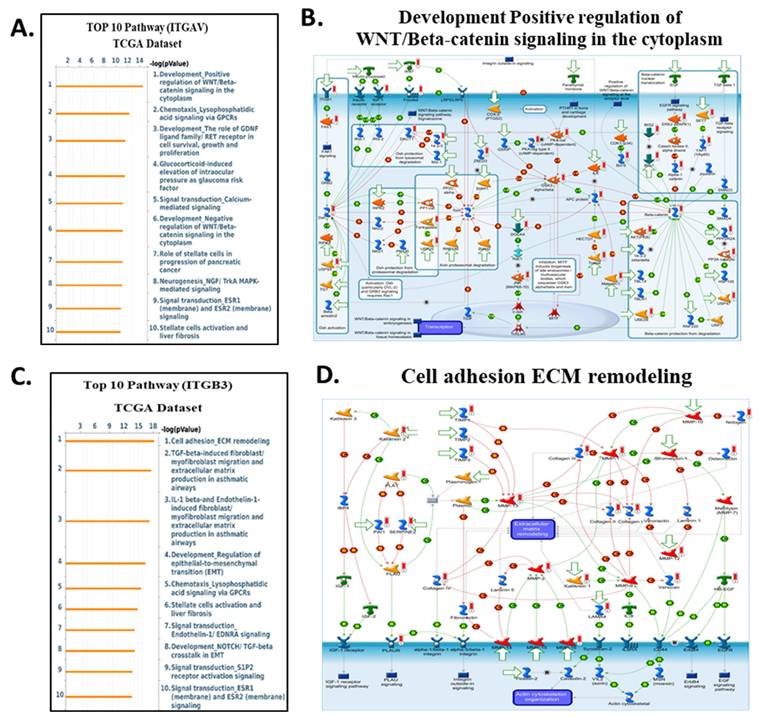

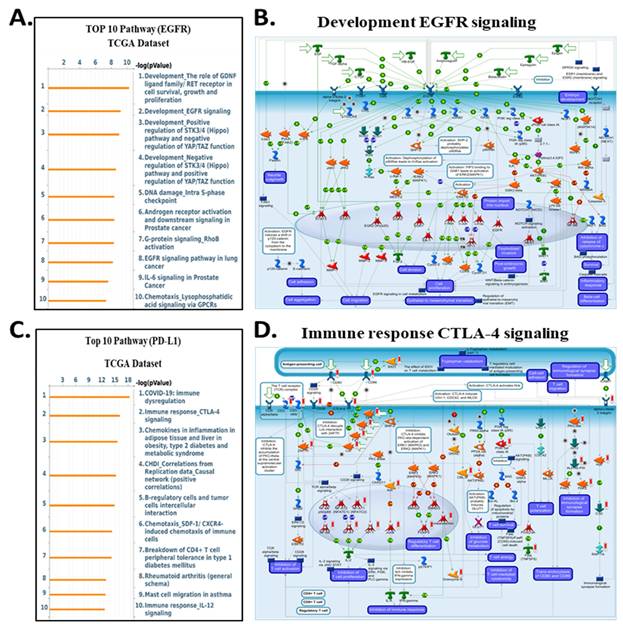

Pathway Enrichment Analysis of Integrin αvβ3, EGFR, and PD-L1 in Cholangiocarcinoma

To clarify the downstream biological programs governed by integrin αvβ3, EGFR, and CD274 (PD-L1) in cholangiocarcinoma, we analyse the MetaCore enrichment results into coherent mechanistic modules rather than listing individual pathways. This allowed us to identify the dominant oncogenic, stromal, and immune circuits that converge downstream of the ITGAV, ITGB3, EGFR, and CD274 expression in the TCGA-CHOL dataset (Fig. 9-10). First, pathway ITGAV, the most prominent enrichments involved ECM remodeling, cytoskeletal reorganization, mechanotransduction, and WNT/β-catenin signaling (Fig. 9A-B). These findings are consistent with the established role of integrin αvβ3 in translating matrix stiffness and stromal cues into intracellular signaling outputs that promote cell adhesion, migration, and EMT-related transcriptional programs. Mechanistically, genes associated with ITGAV expression were embedded in pathways regulating fibroblast activation, LOX/LOXL1-mediated matrix crosslinking, and GPCR-mediated chemotaxis, reinforcing the central role of αvβ3 in coordinating extracellular matrix-derived signals during tumor progression. Similarly, ITGB3 expression correlated strongly with pathways associated with epithelial-mesenchymal transition, TGF-β-NOTCH crosstalk, and cell adhesion dependent signaling (Fig. 9C-D). MetaCore network maps highlighted increased integrin-FAK interactions, ECM degradation, and cytoskeletal rearrangement, all of which support the notion that ITGB3 enhances cellular plasticity and invasive remodeling within the cholangiocarcinoma microenvironment. These results position integrin αvβ3 as a key upstream regulator of structural and transcriptional reprogramming in CCA.

Validation of the protein expression levels of EGFR, integrin αvβ3 in normal bile duct tissue and cholangiocarcinoma tissues. (A) ITGAV, (B) ITGB3, (C) EGFR and (D) CD274(PD-L1) protein expression were analyzed in bile ducts cholangiocarcinoma tissues using HPA database. HPA, the human protein atlas.

Top enriched pathways and signaling diagrams associated with ITGAV and ITGB3 in the TCGA dataset. (A) Top 10 enriched pathways correlated with ITGAV expression in the TCGA dataset, ranked by -log₁₀(p-value). Prominent pathways include WNT/β-catenin signaling, chemotaxis via GPCRs, and MAPK-mediated signaling. (B) Metacore diagram depicting the WNT/β-catenin signaling cascade, highlighting molecules correlated with ITGAV expression. Molecules upregulated are marked in red, downregulated in green, with z-score predictions shown in orange (activation) or blue (inhibition). (C) Top 10 enriched pathways associated with ITGB3 expression in the TCGA dataset. Key pathways include cell adhesion and extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling, TGF-β signaling, and EMT regulation. (D) Metacore diagram of ECM remodeling and integrin signaling associated with ITGB3 expression. Color coding, as in panel B, illustrates the predicted regulatory effect.

In contrast, genes correlated with EGFR expression enriched for classical oncogenic pathways, including RET/FGFR-MAPK signaling, Hippo-YAP/TAZ regulation, growth factor-mediated migration, and DNA damage-associated signaling (Fig. 10A-B). These enrichments are consistent with EGFR's known involvement in proliferative and survival pathways, and they align with prior reports demonstrating that integrin-mediated EGFR cross-activation amplifies ERK and PI3K/AKT output to support tumor progression. For CD274 (PD-L1), MetaCore analysis highlighted immune-related pathways such as CTLA-4 signaling, cytokine-driven tolerance, chemokine responses, and T-cell exhaustion signatures (Fig. 10C-D). These findings reinforce the functional linkage between inflammatory transcriptional programsparticularly those involving STAT3, NF-κB, and β-catenin and PD-L1 upregulation, supporting a tumor cell-intrinsic mechanism of immune suppression in cholangiocarcinoma. Supplementary Figures S1-S8 and Supplementary Tables S2-S5 further expand these observations, providing complete lists of enriched pathways, gene networks, and statistical associations. Together, these analyses reveal that ITGAV, ITGB3, EGFR, and CD274 converge on interconnected processes involving ECM remodeling, mechanotransduction, proliferative ERK/AKT signaling, transcriptional plasticity, and immune escape. This integrated MetaCore framework aligns closely with the central signaling architecture of our study and strengthens the therapeutic rationale for targeting the ITGAV/ITGB3-EGFR-PD-L1 axis in cholangiocarcinoma.

Collectively, these pathway findings position integrin αvβ3 as a master regulator of the molecular circuitry that shapes cholangiocarcinoma aggressiveness. Rather than functioning as a passive adhesion receptor, αvβ3 integrates cues from the extracellular matrix with intracellular growth factor signaling to coordinate ERK- and AKT-dependent proliferation, STAT3-driven inflammatory transcription, β-catenin-mediated plasticity, and PD-L1-associated immune evasion. MetaCore-derived networks consistently converged on these signaling hubs, and the corresponding pathway activation patterns were strongly reflected in our transcriptomic and cellular phenotypes across ITGAV-, ITGB3-, EGFR-, and CD274-high tumors. Importantly, the alignment between computational enrichment and functional data highlights a highly interconnected signaling axis in which αvβ3 amplifies EGFR activity, stabilizes β-catenin, reinforces EMT programs, and enhances PD-L1 expression to support tumor progression and immune suppression. These integrated observations underscore the therapeutic relevance of targeting αvβ3 by binding to the extracellular domain of the integrin, DL-N2 derivatives have the potential to dampen multiple oncogenic circuits simultaneously, offering a rational strategy to disrupt the ITGAV/ITGB3-EGFR-STAT3/β-catenin-PD-L1 axis and overcome multifaceted pathogenic mechanisms in cholangiocarcinoma.

Top enriched pathways and signaling diagrams associated with PD-L1 and EGFR expression in the TCGA dataset. (A) Top 10 enriched pathways associated with EGFR expression in the TCGA dataset. Key pathways include RET/FGFR signaling, Hippo-YAP/TAZ pathway regulation, DNA damage response, and EGFR signaling in cancer progression. (B) Metacore diagram showing development and oncogenic signaling networks associated with EGFR expression. Major pathways include EGFR and GPCR signaling, cell proliferation, and migration pathways. As described in panel B, color coding highlights molecular expression and predicted regulatory outcomes. (C) Top 10 enriched pathways correlated with PD-L1 expression, ranked by -log₁₀(p-value). Prominent pathways include immune dysregulation in COVID-19, CTLA-4 signaling, chemokine signaling in inflammation, and T-cell tolerance and migration, reflecting the immune regulatory role of PD-L1. (D) Metacore signaling diagram illustrating immune-related pathways associated with PD-L1 expression. Key elements include T-cell activation, antigen presentation, and cytokine signaling. Nodes are colored to reflect gene expression: red for upregulated, green for downregulated. Predicted pathway activity is shown in orange (activation) and blue (inhibition).

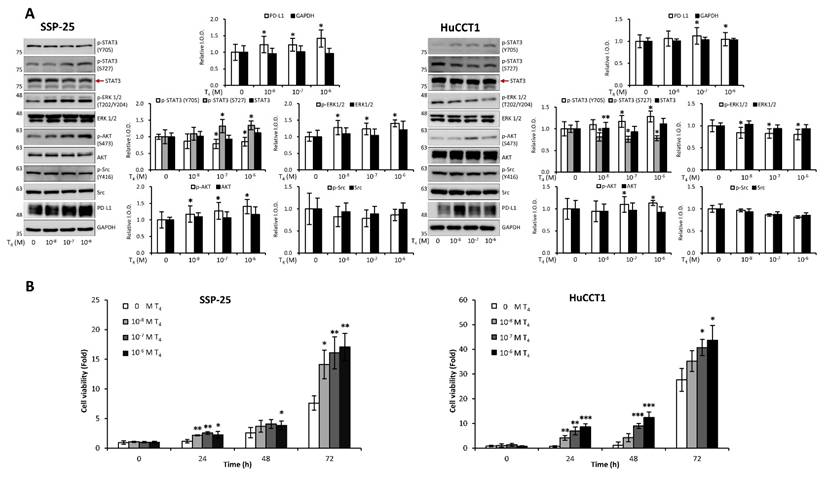

Thyroxine modulates signal transduction pathways in cholangiocarcinoma cells. (A). T4 modulates signal transduction pathways in cholangiocarcinoma cells. Serum-starved SSP-25 (left) and HuCCT1 cells (right) were left unstimulated or were stimulated with various concentrations of T4 (10-8, 10-7, and 10-6 M) for 24 h. Cells that did not receive stimulation with T4 were treated with KOH-PG buffer instead. After stimulation, the cells were lysed, and cell lysates were subjected to Western blotting to detect p-ERK1/2, ERK1/2, p-AKT, AKT, p-STAT3 (Ser727), p-STAT3 (Tyr705), STAT3, p-Src, Src, and PD-L1; GAPDH was used as a loading control for protein normalization. Quantitative results are expressed as relative integrated optical densities (IODs) by defining the amounts of the indicated detected proteins in unstimulated cells as 1. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. * p < 0.05 compared to unstimulated cells. (B). Thyroid hormone affects the growth of cholangiocarcinoma cells. Serum-starved SSP-25 (left) and HuCCT1 cells (right) were left unstimulated or stimulated with various concentrations of T4 (10-8, 10-7, and 10-6 M) for the indicated times. Cells that did not receive stimulation with T4 were treated with KOH-PG buffer instead. After stimulation, the cells were subjected to the alamar blue cell viability assay. The quantitative results were expressed as fold changes by defining the viability of the unstimulated group of each cell line at 0 h as 1. Data are represented as the mean ± SD of triplicate cultures in three independent experiments. * p < 0.05 and ** p < 0.01 compared to T4-unstimulated cells at the same time point.

Thyroxine and EGF Induce Different Signaling Pathways to Stimulate Proliferation in KRAS Wild-Type SSP-25 Cells and KRAS Mutant HuCCT1 Cells

Clinical studies highlight the role of integrin αvβ3 in cholangiocarcinoma, so we further examined thyroxine (T4) signaling in CCA cell models representing different anatomical origins. SSP-25 and HuCCT1 cells, both derived from intrahepatic CCA, and TFK-1, originating from perihilar CCA, provided a relevant platform to evaluate subtype-related signaling behavior. In KRAS wild-type SSP-25 cells, T4 activated ERK1/2 and AKT beginning at 10⁻⁸ M and induced STAT3 phosphorylation at 10⁻⁷ M without affecting Src (Fig. 11A, left). In KRAS-mutant HuCCT1 cells, T4 showed an opposite pattern: ERK1/2 and STAT3 (S727) were suppressed at 10⁻⁸ M, whereas STAT3 (Y705) and AKT were activated from 10⁻⁷ M onward (Fig. 11A, right). These results indicate that T4 engages integrin αvβ3 to regulate ERK, STAT3, and AKT signaling in a KRAS-dependent manner, and that these responses may differ across intrahepatic and extrahepatic CCA models. Studies suggest that thyroxine promotes cancer cell proliferation across various cancer types. We sought to determine whether thyroxine specifically stimulates cell growth in different KRAS status cholangiocarcinoma cells. KRAS wild-type SSP-25 and KRAS mutant HuCCT1 cells were stimulated with various concentrations of thyroxine for 24, 48, and 72 h to assess its effects on cell proliferation. T4 induced cell growth in SSP-25 cells starting at 10⁻⁸ M during the 24 to 72 h treatment period, whereas HuCCT1 cell growth was significantly stimulated at 10⁻⁷ and 10⁻⁶ M during the same period (Fig. 11B, right).

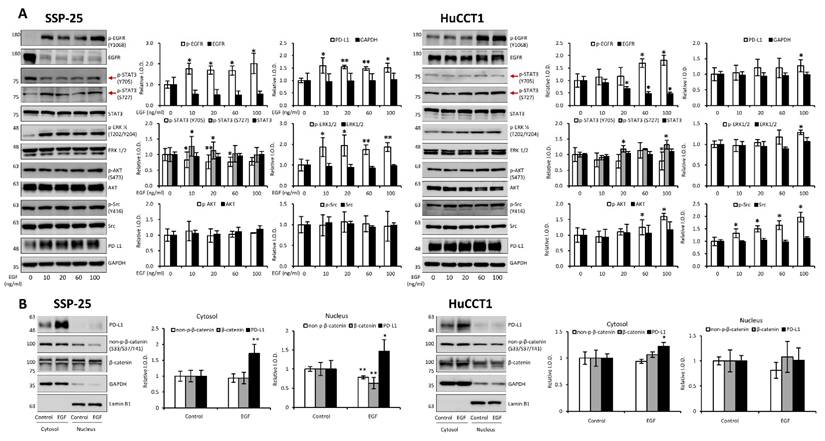

EGF modulates signal transduction pathways in cholangiocarcinoma cells. (A). EGF modulates signal transduction pathways. Serum-starved SSP-25 (left) and HuCCT1 cells (right) were left unstimulated or were stimulated with various concentrations of EGF (10, 20, 60, and 100 ng/ml) for 24 h. Cells that did not receive stimulation with EGF were instead treated with PBS. After stimulation, the cells were lysed, and cell lysates were subjected to Western blotting to detect p-EGFR, EGFR, p-ERK1/2, ERK1/2, p-AKT, AKT, p-STAT3 (Ser727), p-STAT3 (Tyr705), STAT3, p-Src, Src, and PD-L1; GAPDH was used as a loading control for protein normalization. Quantitative results are expressed as relative integrated optical densities (IODs) by defining the amounts of the indicated detected proteins in unstimulated cells as 1. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. * p < 0.05 and ** p < 0.01 compared to unstimulated cells. (B). EGF stimulation does not affect the translocation of PD-L1 from the cytosol to the nucleus in cholangiocarcinoma cells. Serum-starved SSP-25 (left) or HuCCT1 (right) cells were left unstimulated or stimulated with 20 or 100 ng/ml EGF, respectively, for 24 h. Cells that did not receive stimulation with EGF were instead treated with PBS. After stimulation, the cells were isolated into nuclear and cytosolic fractions, and then the cell lysates were subjected to Western blotting to detect PD-L1, non-p-β-catenin (Ser33/Ser37/Tyr41), and β-catenin; Lamin B1 and GAPDH were used as loading controls for nuclear and cytosolic fractions, respectively.

EGF has been shown to promote cholangiocarcinoma growth [35]. However, KRAS wild-type SSP-25 cells showed greater sensitivity to EGF treatment [35]. To further elucidate the molecular mechanisms, we investigated the signal transduction pathways activated by EGF in KRAS wild-type SSP-25 and KRAS mutant HuCCT1 cells. EGF treatment induced the activation of ERK1/2, AKT, and STAT3 pathways in both cancer cell lines, suggesting that EGF activated common signaling pathways to stimulate cancer cell proliferation (Fig. 12A). EGFR and T4 share common signaling pathways, indicating the availability of signaling crosstalk in stimulating tumor growth. These findings highlighted the complexity of cholangiocarcinoma signaling and suggested that KRAS mutation influences the cellular signaling pathways activated by thyroxine (T4) and EGF, further complicating the tumor's response to these molecules.

It has been reported that thyroxine-induced nuclear translocated PD-L1 plays a vital role in cancer cell proliferation [36]. Further evidence indicates that nuclear PD-L1 promotes angiogenesis in malignancies [37]. To investigate whether EGF induces nuclear PD-L1 translocation, SSP-25 (Fig. 12B, left) and HuCCT1 (Fig. 12B, right) were stimulated with EGF for 24 h. Under EGF stimulation in these two cell lines, the upregulated PD-L1 was primarily found in the cytosol of both cell lines. However, a slight increase in nuclear PD-L1 was observed only in KRAS wild-type SSP-25 cells. In contrast, KRAS mutant HuCCT1 cells did not exhibit nuclear PD-L1 accumulation (Fig. 12B). EGFR activation leads to β-catenin-mediated PD-L1 expression, promoting immune evasion in glioblastoma [38]. In EGF-stimulated SSP-25 cells (Fig. 12B, left) but not in HuCCT1 cells (Fig. 12B, right), a decrease in total levels of non-p-β-catenin and total β-catenin was observed in the nuclear fraction, suggesting p-β-catenin increased. Thus, EGF increased cytosolic PD-L1 expression, likely through β-catenin activation [39] in cholangiocarcinoma.

Targeting Integrin αvβ3 Inhibits Cholangiocarcinoma Growth In Vitro and In Vivo

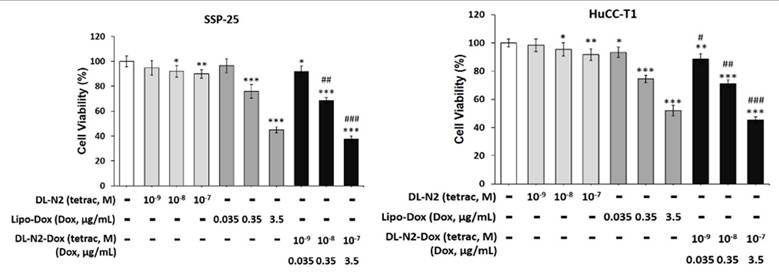

We investigated targeting integrin αvβ3 to inhibit cholangiocarcinoma growth by a liposome-linked tetraiodothyroacetic acid (DL-N2). Two cholangiocarcinoma cell lines, SSP-25 and HuCCT1 cells, were treated with DL-N2, Lipo-Dox, or DL-N2 payload with Dox (DL-N2-Dox) to assess their cytotoxic effects (Fig. 13). SSP-25 and HuCCT1 cells were exposed to a single dose of varying concentrations of DL-N2, Lipo-Dox, or DL-N2-Dox and incubated for three days. Following incubation, the cells were harvested for cytotoxicity assays to assess the effects of the treatments. DN-N2, Lipo-Dox, and DL-N2-Dox reduced cell viability in both cholangiocarcinoma cell lines. Notably, the DL-N2-Dox exhibited a more substantial antiproliferative effect on cancer cells (Fig. 13). This treatment also significantly suppressed cholangiocarcinoma proliferation, particularly in KRAS wild-type SSP-25 cells.

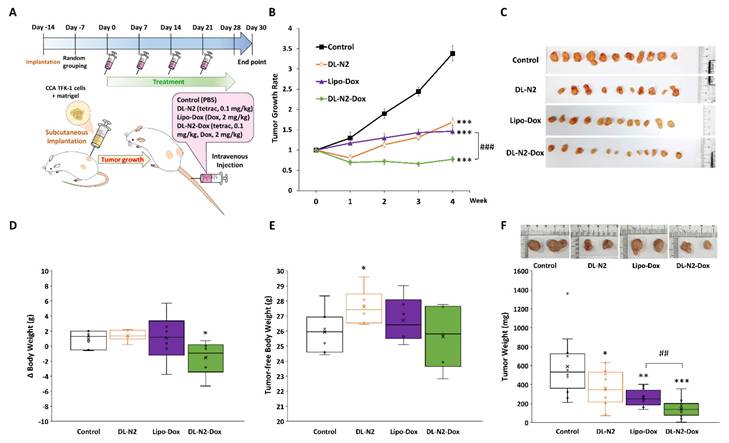

Next, we conducted the anti-tumor growth effect of DL-N2 and its derivatives in cholangiocarcinoma xenografted mice. Since cholangiocarcinoma SSP-25 and HuCCT1 cells exhibit slow growth (doubling times of 64 and 55 hours, respectively) and have difficulty forming tumors in xenografted animals, 1 × 107 cholangiocarcinoma TFK-1 cells were inoculated in mice as described in the Materials and Methods. After the TFK-1 cells had grown for 14 days and formed tumors, mice were intravenously injected with DL-N2 (tetrac 0.1 mg/kg), Lipo-Dox (Dox 2mg/kg), or DL-N2-Dox (tetrac 0.1 mg/kg, Dox 2mg/kg) once per week for four weeks. The schematic protocol of the cholangiocarcinoma xenograft model is presented in Fig. 14A. DL-N2, Lipo-Dox, and DL-N2-Dox all significantly reduced tumor growth rates compared with the control group. DL-N2 and DL-N2-Dox significantly reduced tumor growth after one week of treatment, whereas Lipo-Dox required two weeks to reduce tumor growth significantly. Moreover, DL-N2-Dox exhibited a markedly more potent effect than Lipo-Dox (Fig. 14B). After 4 weeks of treatment, mice were sacrificed, and tumors were harvested and weighed. The xenograft tumors were collected from each group and are presented in Fig. 14C. It was observed that the tumors treated with liposomal drugs, DL-N2, Lipo-Dox, or DL-N2-Dox, were significantly smaller than those in the control group. Among all treatment groups, the tumors in the DL-N2-Dox group were remarkably small, exhibiting the most significant size reduction. After treatment, the weight changes of mice in the DL-N2 and Lipo-Dox groups were not significantly different from those in the control group. However, the weight changes of mice in the DL-N2-Dox group differed from those in the control group (Fig. 14D). Additionally, the tumor-free body weight of mice in the DL-N2 group was significantly higher than that of the control group. In contrast, no significant difference was observed in the tumor-free body weight of mice in the Control, Lipo-Dox, and DL-N2-Dox groups (Fig. 14E). The tumor weights of DL-N2, Lipo-Dox, and DL-N2-Dox were significantly lower than those in the control group, with the tumor weight of DL-N2-Dox being considerably lighter than that of Lipo-Dox (Fig. 14F). Similarly, based on the overall results, the changes in body weight observed in the control group were attributed to tumor growth. In contrast, the significant decrease in body weight change in the DL-N2-Dox group was due to tumor reduction. Furthermore, DL-N2 effectively inhibited tumor growth and prevented weight loss. In contrast to the control group, where tumor burden contributed to weight changes, the DL-N2 group exhibited an increase in tumor-free body weight, further demonstrating the biological safety of DL-N2.

DL-N2 and DL-N2-Dox induced cytotoxicity in cholangiocarcinoma cells. A. SSP-25 cells and B. HuCCT1 cells were treated with DL-N2 (10-9 to 10-7 M), Lipo-Dox (0.035 µg/ml to 3.5 µg/ml) or DL-N2-Dox for 3 days. Cells were harvested, and cytotoxicity assays were conducted. Cells were harvested, and cytotoxicity assays were conducted. Data are presented as the mean ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001 as compared with control. #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001 as compared with corresponded Lipo-Dox.

DL-N2 and DL-N2-Dox inhibited the tumor growth in cholangiocarcinoma TFK-1 xenograft study. (A) Schematic protocol of cholangiocarcinoma xenograft model. After TFK-1 cancer cell inoculation in the NOD SCID mice, the mice were treated with solvent (PBS), DL-N2 (tetrac, 0.1 mg/kg), Lipo-Dox (Dox, 2 mg/kg) or DL-N2-Dox (tetrac, 0.1 mg/kg, Dox, 2 mg/kg) one dose per week for 4 weeks. After 4 weeks of treatment, mice were sacrificed, and tumors were harvested and weighed. (B) The growth rate of CCA tumors during the experiment. The growth curve of tumor volume is normalized to the volume at the beginning of the treatment. Data are shown as Mean ± SEM. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 as compared with control. ###p<0.001, as compared with Lipo-Dox. (C) Images of xenografted tumors collected from each group. (D) Changes in body weight over the 4-week treatment. (E) Tumor-free body weight of xenograft mice, calculated by subtracting tumor weight from the total body weight of each mouse on the day of sacrifice. (F) The weight of CCA tumors collected from the sacrificed mice. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, as compared with control. ##p<0.01, as compared with Lipo-Dox.

Discussion

Cholangiocarcinoma represents a biologically heterogeneous group of biliary tract cancers composed of intrahepatic (iCCA), perihilar (pCCA), and distal (dCCA) subtypes [6]. These entities differ markedly in stromal architecture, immune infiltration, and dominant oncogenic pathways, creating major challenges for therapeutic development. The public datasets used in this study including TCGA-CHOL and available single-cell atlases are predominantly derived from intrahepatic CCA, as large-scale transcriptomic resources for pCCA and dCCA remain limited [40]. This imbalance has hindered a comprehensive understanding of how integrin αvβ3, EGFR, and PD-L1 signaling operate across the full spectrum of CCA subtypes. Nevertheless, the biological divergence among these subtypes strongly suggests that integrin-centered signaling hubs may not be uniformly conserved. iCCA, for example, is characterized by a dense desmoplastic reaction and LOXL1-enriched matrix that enhances mechanotransduction through αvβ3 and amplifies downstream YAP/TAZ, STAT3, and β-catenin activation [41, 42]. In contrast, pCCA) and dCCA often exhibit distinct ductal architecture, bile flow dynamics, and inflammatory microenvironments that may influence FN1/COL1A1 integrin-EGFR crosstalk or alter dependence on αvβ3-mediated adhesion and invasion [43]. Interestingly, despite these differences, ITGAV, ITGB3, and EGFR remain tightly co-expressed across multiple datasets, suggesting that αvβ3-driven signaling may represent a shared pathogenic axis across CCA subtypes, although with subtype-specific intensities rather than entirely distinct mechanisms. Future subtype-stratified analyses using balanced sampling, spatial transcriptomics, and stromal cell-resolved profiling will be essential to determine whether αvβ3 represents a universal therapeutic node across cholangiocarcinoma or a selectively targetable vulnerability enriched within iCCA.

Our analysis indicates that integrin αvβ3 regulates PD-L1 expression through a primarily tumor cell-intrinsic mechanism, rather than via macrophage-dependent mechanotransduction. All in vitro experiments were conducted in purified cholangiocarcinoma cell lines devoid of immune or stromal components, allowing us to isolate integrin-EGFR intracellular crosstalk. Under these conditions, integrin αvβ3 activation enhanced the FAK/SRC, ERK1/2, AKT, β-catenin, and STAT3 pathways canonical transcriptional regulators of PD-L1. The rapid induction of PD-L1 following T4 or EGF stimulation, and its equally rapid suppression by tetrac or DL-N2, further supports a direct signaling relationship. Although macrophage mechanotransduction and matrix stiffness may modulate PD-L1 in vivo, these influences were absent from our experimental system. Thus, our findings support a model in which integrin-dependent signaling upregulates PD-L1 directly within malignant cholangiocarcinoma cells. Future work incorporating tumor-immune co-culture or spatial profiling could help delineate additional microenvironmental contributions that may shape the therapeutic potential of integrin-ICI combinations.

Previous work has studied integrins or EGFR in isolation, but a unified mechanistic framework linking integrin αvβ3, EGFR, STAT3/β-catenin activation, and PD-L1 induction in cholangiocarcinoma has not been established [44, 45]. Likewise, the interplay between thyroid hormone signaling, EGFR activity, and KRAS mutational status remains poorly defined. Few studies have explored how integrin αvβ3 contributes to immune-cell recruitment, how stromal ligands shape integrin activation, or how integrin inhibition could cooperate with EGFR-targeted therapy in KRAS-mutant CCA [46, 47]. These knowledge gaps limit the translational rationale for developing integrin-targeted therapeutics.

Also, these translational challenges surrounding integrin-directed therapies reflect lessons learned from earlier clinical programs. Several αvβ3 antagonists, including cilengitide, failed to demonstrate durable clinical benefit owing to suboptimal pharmacokinetics, poor tumor penetration, and lack of integrin-selective patient stratification [48]. Many early trials relied on pan-integrin inhibition or high-affinity ligands that paradoxically reduced vascular delivery and tissue exposure [49]. Importantly, these therapeutic attempts occurred in tumor types with limited stromal stiffness or weak integrin dependence. More recent studies emphasize the need for affinity tuning, specificity for pathological rather than physiological integrin states, and rational combination strategies with EGFR inhibitors or immune checkpoint blockade. In contrast to prior settings, cholangiocarcinoma presents a markedly integrin-dependent stromal landscape, characterized by LOXL1-driven matrix crosslinking, strong αvβ3-EGFR-STAT3/β-catenin co-activation, and robust PD-L1 induction [43]. These features provide a mechanistically grounded rationale for revisiting αvβ3-targeted therapy. DL-N2 derivatives, which selectively bind the extracellular domain of integrin αvβ3 and disrupt downstream EGFR-STAT3-β-catenin signaling, overcome several limitations of earlier integrin inhibitors and represent a renewed therapeutic opportunity suited to the unique biology of CCA.

In this study, we addressed these gaps by integrating bulk transcriptomics (TCGA-CHOL), single-cell RNA sequencing datasets (GSE138709 and GSE142784), protein-level validation, mechanistic signaling assays in KRAS wild-type and KRAS-mutant CCA cell lines, and xenograft models to define the integrin αvβ3-EGFR-PD-L1 signaling axis in cholangiocarcinoma. Our findings identify integrin αvβ3 as a central pathogenic hub that links ECM remodeling, EGFR activation, STAT3/β-catenin signaling, and PD-L1-mediated immune modulation, and they demonstrate that DL-N2 derivatives inhibit these pathways through integrin-directed targeting [6, 34, 38-41].

Our study also explored the pathogenic role of integrin αvβ3 in cholangiocarcinoma and its potential as a therapeutic target. Our results prove that integrin αvβ3 was significantly upregulated in cholangiocarcinoma tissues compared to normal patients' samples (Fig. 2 and 6). Integrin αvβ3 plays vital roles in cell adhesion, migration, and invasion, which are essential for tumor metastasis [10, 50]. Integrin αvβ3 is known to interact with the extracellular matrix, promoting the metastatic spread of cancer cells [12]. Patients with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma show an elevated level of lysyl oxidase-like 1 (LOXL1) in the tissues and sera compared to nontumor tissues and the sera of unaffected individuals [51]. Overexpression of LOXL1 promotes cell proliferation, colony formation, and metastasis in vivo and in vitro and induced angiogenesis via the interaction with fibulin 5 (FBLN5) to bind with integrin αvβ3 and activate the FAK-MAPK signaling pathway inside vascular endothelial cells [51]. Thyroid hormone binds to the extracellular domain of integrin αvβ3 on endothelial cells. It controls the transcription of specific vascular growth factor genes, regulates growth factor receptor/growth factor interactions, and stimulates endothelial cell migration to a vitronectin cue [52]. On the other hand, in HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors, lovastatin inhibits the expression of integrin β3 and cell surface heterodimer integrin αvβ3 and downstream signaling, including FAK activation, and β-catenin, vimentin, ZO-1, and β-actin [53]. The consequence downregulates the expressions of transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1, cyclooxygenase (COX)-2, and intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)-1 [53] and affects cell adhesion [53]. Integrin αvβ3 is upstream of EGFR to modulate EGFR-dependent activities (Fig. 3). EGFR and integrin αv might work synergistically to promote cancer cell migration and invasion, key processes in tumor metastasis (Fig. 9-10).

Our findings highlight the importance of integrin αvβ3 in cholangiocarcinoma progression and support the hypothesis that targeting integrin αvβ3 may potentially inhibit EGFR-dependent pathogenic effects via crosstalk effects. Therefore, targeting integrin αvβ3 could provide a novel therapeutic approach for this aggressive malignancy. EGFR has long been recognized as a key player in cancer progression, primarily due to its involvement in regulating cell proliferation, survival, and migration [14]. We also observed a strong correlation between EGFR and integrin αvβ3 expression (Fig. 2), suggesting that these two molecules may work synergistically to promote cholangiocarcinoma progression. Thyroxine via integrin αvβ3 (Fig. 11) and EGF via EGFR (Fig. 12) activated different signal transduction pathways in cholangiocarcinoma progression (Fig. 9-10) and immune modulation (Fig. 4). Additionally, we demonstrated that modulating integrin αvβ3 activity by tetraiodothyroacetic acid (tetrac), a derivative of L-thyroxine (T4), inhibited EGFR-delivered signal pathways and activities [54]. DL-N2 acts directly at the thyroid hormone receptor site located on the extracellular domain of the integrin αvβ3 heterodimer. Structural analyses show that this ligand-binding pocket is formed at the interface of the αv S1 domain and the β3 I-like domain, meaning that effective binding requires the intact αvβ3 complex. DL-N2 does not bind αv or β3 individually. Prior functional knockdown studies demonstrate that β3 plays the dominant signaling role because β3 silencing nearly abolishes tetrac- and nano-tetrac-mediated inhibition of downstream pathways, whereas αv knockdown produces only partial loss of responsiveness. These findings suggest that β3-driven signaling transduction is the primary determinant of DL-N2 tumor-suppressive activity, supporting our observation that DL-N2 suppresses both integrin-driven and EGFR-dependent signaling via pathway crosstalk [23, 24].