Impact Factor

ISSN: 1449-1907

Int J Med Sci 2026; 23(2):510-519. doi:10.7150/ijms.127638 This issue Cite

Research Paper

Missense and Intronic Variants in HNF1A Affect Prostate Cancer Aggressiveness in Patients with Biochemical Recurrence

1. Division of Urology, Department of Surgery, Tungs' Taichung Metro Harbor Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan.

2. Department of Life Science, College of Life Science, National Chung Hsing University, Taichung, Taiwan.

3. Graduate Institute of Clinical Medicine, College of Medicine, Taipei Medical University, Taipei, Taiwan.

4. International Master/PhD Program in Medicine, College of Medicine, Taipei Medical University, Taipei, Taiwan.

5. Department of Urology, Wan Fang Hospital, Taipei Medical University, Taipei, Taiwan.

6. Department of Urology, School of Medicine, College of Medicine and TMU Research Center of Urology and Kidney (TMU-RCUK), Taipei Medical University, Taipei, Taiwan.

7. Division of Urology, Department of Surgery, Taichung Veterans General Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan.

8. School of Medicine, Chung Shan Medical University, Taichung, Taiwan.

9. School of Medicine, National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University, Taipei, Taiwan.

10. Department of Mathematics and Statistics, Florida Atlantic University, Boca Raton, Florida, United States.

11. Institute of Medicine, Chung Shan Medical University, Taichung, Taiwan.

12. Department of Medical Research, Chung Shan Medical University Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan.

13. Pulmonary Research Center, Wan Fang Hospital, Taipei Medical University, Taipei, Taiwan.

14. Traditional Herbal Medicine Research Center, Taipei Medical University Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan.

15. TMU Research Center of Cancer Translational Medicine, Taipei Medical University, Taipei, Taiwan.

16. School of Medical Laboratory Science and Biotechnology and Ph.D. Program in Medical Biotechnology, College of Medical Science and Technology, Taipei Medical University, Taipei, Taiwan.

Received 2025-10-31; Accepted 2025-12-15; Published 2026-1-1

Abstract

Prostate cancer (PCa) is a genetically and phenotypically heterogeneous disease, and further advancements in PCa biomarker discovery are urgently required. Hepatocyte nuclear factor 1 A (HNF1A), a transcription factor, plays a critical role in PCa progression after biochemical recurrence (BCR). However, studies investigating the impact of HNF1A genetic variants on PCa are scarce. Therefore, in this study, we explored the associations of HNF1A single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) with susceptibility to BCR in PCa and its clinicopathological development. Two nonsynonymous (missense) SNPs [rs2464196 (S487N) and rs1169288 (I27L)] and two intronic SNPs [rs1169286 and rs735396] were analyzed using a TaqMan allelic discrimination assay for genotyping in a cohort of 690 Taiwanese patients with PCa. The results demonstrated that patients with PCa carrying the HNF1A rs735396 (TC+CC), rs2464196 (GA+AA), or rs1169288 (AC+CC) had a higher risk of developing tumors with higher pathological Gleason grades (3-5). These associations were particularly evident in the BCR subpopulation. Moreover, analysis of data from The Cancer Genome Atlas revealed that HNF1A expression was higher in PCa tissues than in normal tissues. Moreover, higher HNF1A expression was correlated with higher Gleason scores, more advanced pathological T stages, and metastasis. Taken together, our findings indicated that elevated HNF1A expression promotes PCa progression and that the missense SNPs rs2464196 and rs1169288, as well as the intronic SNP rs735396, may influence HNF1A expression, thereby influencing PCa aggressiveness, particularly in patients with BCR.

Keywords: prostate cancer, hepatocyte nuclear factor 1 alpha, single-nucleotide polymorphism, biochemical recurrence, clinicopathologic progression

Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) is estimated to account for 288,300 new cases in the United States; it is the most frequently diagnosed cancer and the second leading projected cause of cancer-related death among men [1]. Most patients with PCa are identified through early-stage prostate-specific antigen (PSA) screening, and early-stage PCa is typically treatable with radical prostatectomy (RP) [2]. However, serum PSA levels can increase after RP, leading to biochemical recurrence (BCR) of PCa and increasing the risks of metastasis and death [2, 3]. Some PCa cases progress rapidly after BCR and transform into an aggressive type of disease called castration-resistant PCa (CRPC). Many patients die of CRPC within 2 years of diagnosis [4]. Consequently, progression to CRPC can be a powerful surrogate marker for PCa prognosis, even in patients undergoing RP and subsequently developing BCR. Several common markers, such as Gleason score, PSA kinetics, lymphovascular invasion, and T stage, have been reported to predict post-RP progression from BCR to CRPC [5, 6]. In addition to these markers, several novel markers are currently under investigation.

Hepatocyte nuclear factor 1A (HNF1A), an HNF1 family protein initially identified in the liver, has been confirmed to be expressed in several organs. HNF1A, located on human chromosome 12q24.3, encodes a transcription factor containing a homeodomain [7]. HNF1A has been noted to have oncogenic roles in various cancers. For example, HNF1A was noted to promote pancreatic cancer stem cell growth [8]. Moreover, elevated HNF1A expression was reported to enhance radiation resistance via PI3K/AKT pathway activation in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma cells [9]. Furthermore, upregulation of both matrix metalloproteinase 14 (MMP14) and HNF1A was reported to promote cell motility and metastasis through induction of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in cervical cancer cells [10]. However, HNF1A has also been noted to have tumor-suppressive roles in certain contexts. For example, HNF1A was reported to increase chemosensitivity to gemcitabine by targeting ABCB1 in pancreatic cancer cells [11]. Furthermore, the combined expression of HNF1A, HNF4A, and forkhead box protein A3 (FOXA3) was noted to inhibit hepatocellular carcinoma cell growth [12].

HNF1A is highly expressed in PCa cells, and its knockdown can suppress tumor growth [13]. Aberrant HNF1A expression was reported to be associated with abbreviated responses to androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) in patients with BCR and progression to CRPC [13]. Moreover, HNF1A is a critical driver of taxane resistance in CRPC [14]. Consequently, targeting HNF1A using bromodomain and extraterminal domain inhibitors was proposed as a therapeutic intervention for CRPC [15]. Although several studies have investigated the functional role of HNF1A in PCa progression, the effects of HNF1A genetic variants on PCa remain unexplored. Missense mutations represent the predominant mutation type of HNF1A in various cancers, including PCa [16]. In the current study, we examined the associations of missense and intronic single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within HNF1A with the risk of BCR and clinicopathological development of PCa in a Taiwanese population.

Materials and Methods

Study populations and ethics

We collected whole-blood samples from 690 patients with PCa who underwent robotic-assisted laparoscopic RP at Taichung Veterans General Hospital (Taichung, Taiwan) between 2012 and 2018. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before venous blood collection, and the study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Taichung Veterans General Hospital (IRB no. CE19062A-2). Clinical data at diagnosis, including pathologic Gleason score, clinical and pathologic T and N stages, seminal vesicle invasion status, perineural invasion status, lymphovascular invasion status, and D'Amico risk classification, were retrieved from the patients' medical records. BCR in the recruited PCa patients was defined as the detection of two consecutive PSA measurements, each exceeding 0.2 ng/mL. This threshold served as an indicator of potential cancer recurrence following initial treatment. In addition, the interval between the two PSA measurements was confirmed to rule out transient fluctuations, ensuring that the elevation represented a true biochemical relapse. This definition is consistent with widely accepted clinical guidelines for post-treatment monitoring in PCa.

Genomic DNA extraction

Whole-blood samples were collected in EDTA-containing tubes and centrifuged. Next, their buffy coats were isolated, and genomic DNA was extracted using a QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. The quality of the extracted DNA was evaluated on a Nanodrop-2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Subsequently, high-quality extracted DNA was used as the template for polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

Selection and determination of HNF1A genetic polymorphisms

Four SNPs in HNF1A were selected for analysis, including two missense variants [rs2464196 (G/A) and rs1169288 (A/C)] and two intronic variants [rs735396 (T/C) and rs1169286 (T/C)]. These SNPs were selected because they may be associated with different cancer types [17-19] or other diseases (e.g., metabolic syndrome and coronary artery disease) [20-22]. We conducted genotyped rs2464196 (assay ID: C___1263617_10), rs1169288 (assay ID: C___7474231_10), rs735396 (assay ID: C___1263608_1_), and rs1169286 (assay ID: C___1263544_20) assays by using TaqMan SNP Genotyping Assay on an ABI StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The detailed procedures for DNA genotyping were described in our previous study [23].

Bioinformatics analysis

RNA expression data and the corresponding clinical information of The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA)-prostate adenocarcinoma (PRAD) cohort were obtained from the UCSC Xena database (https://xena.ucsc.edu/) (dataset ID: TCGA-PRAD.star_tpm.tsv). The database provides gene expression data in the log2(TPM+1) format; thus, we converted these data back to the TPM (i.e., transcripts per million) format for subsequent analyses. Clinical variables, including Gleason scores and TNM stages, were extracted, and all data were organized according to the corresponding TCGA IDs. Differences between two independent groups were assessed using an unpaired Student's t test, whereas a paired Student's t test was applied for groups with NT-paired samples. For comparisons across multiple groups, we performed one-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey's post hoc test. Spearman correlation analysis was used to identify genes correlated with HNF1A. These genes were then ranked according to their correlation coefficients and subjected to gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA). Pathways with a false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Overall survival (OS) was assessed by categorizing patients with PRAD into high- and low-HNF1A expression groups according to the best cutoff values, and statistical significance was determined using the log-rank test.

Statistical analysis

Between-group differences in demographic characteristics were analyzed using the chi-square and Student's t tests. Associations between genotypic frequencies and clinicopathological features were examined using multivariate logistic regression models, with these yielding odds ratios (ORs) and adjusted ORs (AORs) with their respective 95% confidence intervals (CIs). All statistical analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.1, 2005, for Windows; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Significance was defined on the basis of p < 0.05.

Results

Demographic characteristics of enrolled patients with PCa

Table 1 presents a comparison of the demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with PCa with postoperative BCR (n = 219) and those without (n = 471). The patients with BCR were more likely to present with advanced clinical T stages (T3-T4) at diagnosis. Furthermore, according to pathological assessment results, the BCR cases more frequently involved higher Gleason grades (3-5) and advanced pathologic T (T3-T4) and N (N1) stages, along with seminal vesicle, perineural, and lymphovascular invasion. According to the D'Amico risk classification, more patients with BCR were classified as being at high risk. In general, the demographic and clinical profiles of our PCa cohort, regardless of BCR status, were comparable to those reported previously [24].

Distributions of demographic characteristics of included patients.

| Variable | BCR | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 471) | Yes (n = 219) | p | |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | |||

| ≤65 | 199 (42.3%) | 90 (41.1%) | 0.775 |

| >65 | 272 (57.7%) | 129 (58.9%) | |

| Pathologic Gleason grade group | |||

| 1 or 2 | 343 (72.8%) | 70 (32.0%) | 0.001* |

| 3, 4, or 5 | 128 (27.2%) | 149 (68.0%) | |

| Clinical T stage | |||

| 1 or 2 | 429 (91.1%) | 164 (74.9%) | 0.001* |

| 3 or 4 | 42 (8.9%) | 55 (25.1%) | |

| Clinical N stage | |||

| N0 | 464 (98.5%) | 212 (96.8%) | 0.138 |

| N1 | 7 (1.5%) | 7 (3.2%) | |

| Pathologic T stage | |||

| 2 | 311 (66.0%) | 52 (23.7%) | 0.001* |

| 3 or 4 | 160 (34.0%) | 167 (76.3%) | |

| Pathologic N stage | |||

| N0 | 459 (97.5%) | 172 (78.5%) | <0.001* |

| N1 | 12 (2.5%) | 47 (21.5%) | |

| Seminal vesicle invasion | |||

| No | 426 (90.4%) | 117 (53.4%) | <0.001* |

| Yes | 45 (9.6%) | 102 (46.6%) | |

| Perineural invasion | |||

| No | 163 (34.6%) | 18 (8.2%) | <0.001* |

| Yes | 308 (65.4%) | 201 (91.8%) | |

| Lymphovascular invasion | |||

| No | 437 (92.8%) | 142 (64.8%) | <0.001* |

| Yes | 34 (7.2%) | 77 (35.2%) | |

| D'Amico risk classification | |||

| Low or Intermediate risk | 266 (56.5%) | 75 (34.2%) | <0.001* |

| High risk | 205 (43.5%) | 144 (65.8%) | |

* p value < 0.05 as statistically significant.

Distribution frequencies of HNF1A genotypes in included patients.

| Variable | BCR | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 471) | Yes (n = 219) | aOR (95% CI) | p | |

| rs735396 | ||||

| TT | 122 (25.9%) | 51 (23.3%) | 1.000 (reference) | |

| TC | 219 (46.5%) | 118 (53.9%) | 0.933 (0.585-1.487) | 0.771 |

| CC | 130 (27.6%) | 50 (22.8%) | 0.747 (0.431-1.294) | 0.298 |

| TC+CC | 349 (74.1%) | 168 (67.7%) | 0.868 (0.559-1.348) | 0.528 |

| rs2464196 | ||||

| GG | 124 (26.3%) | 53 (24.2%) | 1.000 (reference) | |

| GA | 220 (46.7%) | 116 (53.0%) | 0.901 (0.568-1.431) | 0.660 |

| AA | 127 (27.0%) | 50 (22.8%) | 0.749 (0.433-1.294) | 0.300 |

| GA+AA | 347 (73.7%) | 166 (75.8%) | 0.849 (0.549-1.314) | 0.462 |

| rs1169288 | ||||

| AA | 168 (35.7%) | 67 (30.6%) | 1.000 (reference) | |

| AC | 221 (46.9%) | 119 (54.3%) | 1.108 (0.724-1.697) | 0.637 |

| CC | 82 (17.4%) | 33 (15.1%) | 0.847 (0.474-1.511) | 0.573 |

| AC+CC | 303 (64.3%) | 152 (69.4%) | 1.036 (0.691-1.552) | 0.865 |

| rs1169286 | ||||

| TT | 136 (28.9%) | 58 (26.5%) | 1.000 (reference) | |

| TC | 224 (47.6%) | 116 (53.0%) | 1.017 (0.650-1.590) | 0.943 |

| CC | 111 (23.5%) | 45 (20.5%) | 0.865 (0.501-1.495) | 0.603 |

| TC+CC | 335 (71.1%) | 161 (73.5%) | 0.968 (0.635-1.475) | 0.878 |

aORs (95% CIs) were estimated using multiple logistic regression models after pathologic Gleason scores, clinical T stages, pathologic T and N stages, seminal vesicle invasion, perineural invasion, lymphovascular invasion, and D'Amico risk classification were controlled for.

Potential impact of HNF1A genetic variants on postoperative BCR in patients with PCa

We next examined the potential influence of four selected HNF1A SNPs [i.e., rs735396 (T/C), rs2464196 (G/A), rs1169288 (A/C), and rs1169286 (T/C)] on postoperative BCR in patients with PCa undergoing RP. The genotype distributions of these SNPs were first evaluated in our cohort of 690 patients, with the most frequent variants being heterozygous T/C, G/A, A/C, and T/C, respectively (Table 2). AORs with 95% CIs were estimated using multivariate logistic regression models controlled for potential confounders to assess the associations between HNF1A SNPs and BCR risk. The analyses revealed no significant associations between these SNPs and postoperative BCR; these results were consistent across both dominant and codominant genetic models (Table 2).

Relationships between clinicopathological features and HNF1A genetic variants in patients with PCa

We further investigated the influence of HNF1A SNPs on the clinicopathological characteristics of PCa, including pathologic T and N stages, Gleason grades, clinical T stage, tumor invasion, and D'Amico risk classification. Regarding the four analyzed HNF1A SNPs, patients with PCa harboring at least one minor allele of rs735396 (TC+CC), rs2464196 (GA+AA), or rs1169288 (AC+CC) demonstrated a significant increase in risk of tumors with higher Gleason grades (3, 4, or 5) compared with those with wildtype homozygotes (ORs = 1.672, 1.635, and 1.399, respectively; Tables 3 and 4). By contrast, rs1169286 was not significantly associated with pathological Gleason grades (Table 4).

Significant correlation of pathological Gleason grades with HNF1A SNPs rs735396 and rs2464196 in PCa patients with BCR

Given the critical role of HNF1A in BCR [13], we stratified patients with PCa into BCR and non-BCR subgroups and assessed the associations between HNF1A SNPs and clinicopathological features in each subgroup. Notably, of the patients with BCR, rs735396 (TC+CC) and rs2464196 (GA+AA) carriers demonstrated significantly higher risks of tumors developing higher Gleason grades (3, 4, or 5) compared with the overall PCa population [OR = 2.628 (95% CI = 1.377-5.017, p = 0.003) and OR = 2.401 (95% CI = 1.268-4.547, p = 0.006), respectively; Tables 5 and 6]. By contrast, these associations were not observed in patients without BCR.

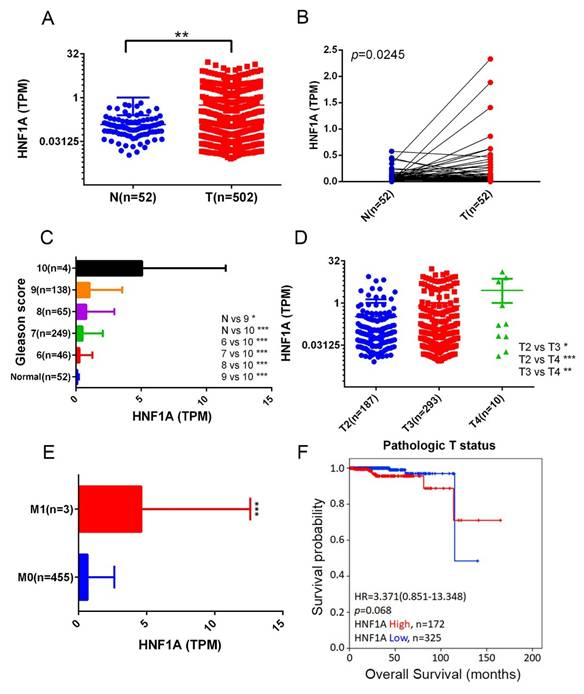

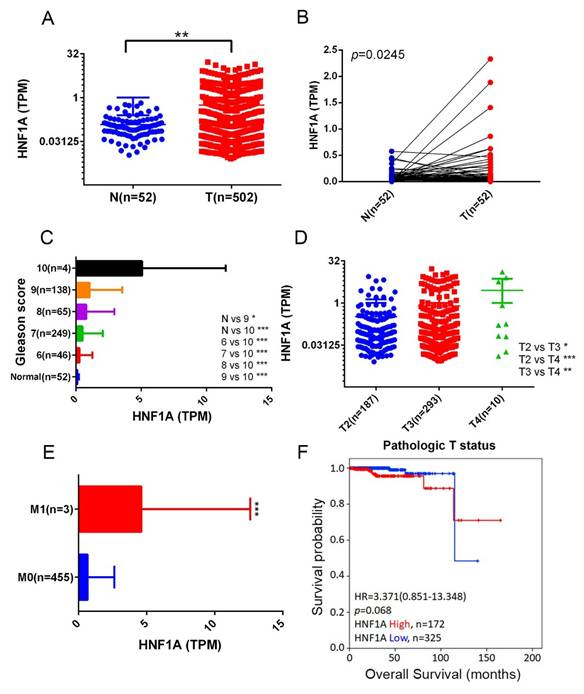

Correlation of elevated HNF1A expression in PCa tissues with higher Gleason scores, larger tumor size, and distant metastasis

We next analyzed HNF1A expression levels in normal and PCa tissues and examined their correlations with PCa progression and prognosis by using data from the TCGA-PRAD dataset. The results demonstrated that HNF1A expression was significantly higher in PCa tissues than in noncancerous tissues (Figure 1A) and their corresponding matched normal counterparts (Figure 1B). Moreover, relative HNF1A transcript levels were elevated in patients with PCa with higher Gleason scores (Figure 1C), advanced T stages (Figure 1D), and distant metastasis (Figure 1E). A Kaplan-Meier analysis further indicated that higher HNF1A expression levels tended to be associated with shorter OS times (Figure 1F).

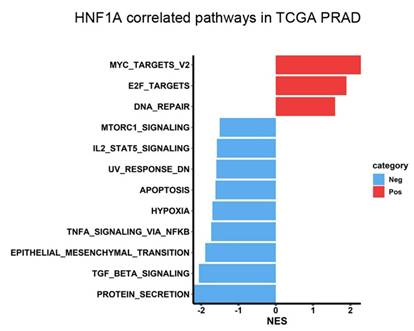

Potential HNF1A-regulated molecular mechanisms underlying PCa progression

To investigate the mechanisms through which HNF1A contributes to PCa progression, we performed GSEA by using data from the TCGA-PRAD dataset. The results demonstrated that “MYC targets” and “E2F targets” were the top two Hallmark gene sets enriched in the HNF1A-high group (Figure 2). Notably, MYC is a major driver of PCa tumorigenesis and progression; elevated MYC expression can accelerate PCa development, increasing Gleason scores and promoting metastasis, BCR, and CRPC development [25, 26]. Moreover, higher E2F expression is associated with higher Gleason scores, advanced tumor stage, metastasis, and elevated BCR risk [27]. Therefore, our results indicated that HNF1A may promote PCa progression by regulating MYC- and E2F-related pathways.

ORs (95% CIs) of the clinical status and HNF1A rs735396 and rs2464196 genotypic frequencies in included patients.

| Variable | rs735396 | rs2464196 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TT (n = 173) | TC+CC (n = 517) | OR (95% CI) | p | GG (n = 177) | GA+AA (n = 513) | OR (95% CI) | p | |

| Pathologic Gleason grade group | ||||||||

| 1 or 2 | 119 (68.8%) | 294 (56.9%) | 1.000 | 0.006* | 121 (68.4%) | 292 (56.9%) | 1.000 | 0.007* |

| 3, 4, or 5 | 54 (31.2%) | 223 (43.1%) | 1.672 (1.160-2.409) | 56 (31.6%) | 221 (43.1%) | 1.635 (1.139-2.348) | ||

| Clinical T stage | ||||||||

| 1 or 2 | 152 (87.9%) | 441 (85.3%) | 1.000 | 0.401 | 156 (88.1%) | 437 (85.2%) | 1.000 | 0.330 |

| 3 or 4 | 21 (12.1%) | 76 (14.7%) | 1.247 (0.744-2.092) | 21 (11.9%) | 76 (14.8%) | 1.292 (0.771-2.166) | ||

| Pathologic T stage | ||||||||

| 2 | 96 (55.5%) | 267 (51.6%) | 1.000 | 0.380 | 97 (54.8%) | 266 (51.9%) | 1.000 | 0.498 |

| 3 or 4 | 77 (44.5%) | 250 (48.4%) | 1.167 (0.826-1.650) | 80 (45.2%) | 247 (48.1%) | 1.126 (0.799-1.586) | ||

| Pathologic N stage | ||||||||

| N0 | 164 (94.8%) | 467 (90.3%) | 1.000 | 0.069 | 168 (94.9%) | 463 (90.3%) | 1.000 | 0.056 |

| N1 | 9 (5.2%) | 50 (9.7%) | 1.951 (0.939-4.055) | 9 (5.1%) | 50 (9.7%) | 2.016 (0.970-4.189) | ||

| Seminal vesicle invasion | ||||||||

| No | 141 (81.5%) | 402 (77.8%) | 1.000 | 0.298 | 144 (81.4%) | 399 (77.8%) | 1.000 | 0.316 |

| Yes | 32 (18.5%) | 115 (22.2%) | 1.260 (0.815-1.950) | 33 (18.6%) | 114 (22.2%) | 1.247 (0.810-1.920) | ||

| Perineural invasion | ||||||||

| No | 50 (28.9%) | 131 (25.3%) | 1.000 | 0.356 | 51 (28.8%) | 130 (25.3%) | 1.000 | 0.365 |

| Yes | 123 (71.1%) | 386 (74.7%) | 1.198 (0.816-1.758) | 126 (71.2%) | 383 (74.7%) | 1.192 (0.814-1.746) | ||

| Lymphovascular invasion | ||||||||

| No | 152 (87.9%) | 427 (82.6%) | 1.000 | 0.102 | 155 (87.6%) | 424 (82.7%) | 1.000 | 0.125 |

| Yes | 21 (12.1%) | 90 (17.4%) | 1.526 (0.916-2.540) | 22 (12.4%) | 89 (17.3%) | 1.479 (0.896-2.442) | ||

| D'Amico risk classification | ||||||||

| Low or intermediate risk | 86 (49.7%) | 255 (49.3%) | 1.000 | 0.930 | 88 (49.7%) | 253 (49.3%) | 1.000 | 0.927 |

| High risk | 87 (50.3%) | 262 (50.7%) | 1.016 (0.720-1.433) | 89 (50.3%) | 260 (50.7%) | 1.016 (0.722-1.430) | ||

ORs with their 95% CIs were estimated using logistic regression models. * p < 0.05 as statistically significant.

ORs (95% CIs) of the clinical status and HNF1A rs1169288 and rs1169286 genotypic frequencies in included patients.

| Variable | rs1169288 | rs1169286 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AA (n = 235) | AC+CC (n = 455) | OR (95% CI) | p | TT (n = 194) | TC+CC (n = 496) | OR (95% CI) | p | |

| Pathologic Gleason grade group | ||||||||

| 1 or 2 | 153 (65.1%) | 260 (57.1%) | 1.000 | 0.043* | 125 (64.4%) | 288 (58.1%) | 1.000 | 0.125 |

| 3, 4, or 5 | 82 (34.9%) | 195 (42.9%) | 1.399 (1.010-1.939) | 69 (35.6%) | 208 (41.9%) | 1.308 (0.928-1.845) | ||

| Clinical T stage | ||||||||

| 1 or 2 | 208 (88.5%) | 385 (84.6%) | 1.000 | 0.163 | 169 (87.1%) | 424 (85.5%) | 1.000 | 0.580 |

| 3 or 4 | 27 (11.5%) | 70 (15.4%) | 1.401 (0.871-2.252) | 25 (12.9%) | 72 (14.5%) | 1.148 (0.704-1.871) | ||

| Pathologic T stage | ||||||||

| 2 | 129 (54.9%) | 234 (51.4%) | 1.000 | 0.388 | 105 (54.1%) | 258 (52.0%) | 1.000 | 0.618 |

| 3 or 4 | 106 (45.1%) | 221 (48.6%) | 1.149 (0.838-1.576) | 89 (45.9%) | 238 (48.0%) | 1.088 (0.780-1.518) | ||

| Pathologic N stage | ||||||||

| N0 | 233 (94.9%) | 408 (89.7%) | 1.000 | 0.020* | 183 (94.3%) | 448 (90.3%) | 1.000 | 0.091 |

| N1 | 12 (5.1%) | 47 (10.3%) | 2.141 (1.112-4.120) | 11 (5.7%) | 48 (9.7%) | 1.782 (0.905-3.509) | ||

| Seminal vesicle invasion | ||||||||

| No | 193 (82.1%) | 350 (76.9%) | 1.000 | 0.114 | 157 (80.9%) | 386 (77.8%) | 1.000 | 0.370 |

| Yes | 42 (17.9%) | 105 (23.1%) | 1.379 (0.925-2.054) | 37 (19.1%) | 110 (22.2%) | 1.209 (0.798-1.833) | ||

| Perineural invasion | ||||||||

| No | 63 (26.8%) | 118 (25.9%) | 1.000 | 0.805 | 50 (25.8%) | 131 (26.4%) | 1.000 | 0.864 |

| Yes | 172 (73.2%) | 337 (74.1%) | 1.046 (0.732-1.494) | 144 (74.2%) | 365 (73.6%) | 0.967 (0.663-1.413) | ||

| Lymphovascular invasion | ||||||||

| No | 204 (86.8%) | 375 (82.4%) | 1.000 | 0.137 | 167 (86.1%) | 412 (83.1%) | 1.000 | 0.332 |

| Yes | 31 (13.2%) | 80 (17.6%) | 1.404 (0.897-2.198) | 27 (13.9%) | 84 (16.9%) | 1.261 (0.789-2.016) | ||

| D'Amico classification | ||||||||

| Low or intermediate risk | 128 (54.5%) | 213 (46.8%) | 1.000 | 0.057 | 95 (49.0%) | 246 (49.6%) | 1.000 | 0.882 |

| High risk | 107 (45.5%) | 242 (53.2%) | 1.359 (0.991-1.864) | 99 (51.0%) | 250 (50.4%) | 0.975 (0.700-1.359) | ||

ORs with their 95% CIs were estimated using logistic regression models. * p < 0.05 as statistically significant.

ORs (95% CIs) of the clinical status and HNF1A rs735396 genotypic frequencies in included patients with or without BCR.

| Variable | No BCR (n = 471) | BCR (n = 219) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TT (n = 122) | TC+CC (n = 349) | OR (95% CI) | p | TT (n = 51) | TC+CC (n = 168) | OR (95% CI) | p | |

| Pathologic Gleason grade group | ||||||||

| 1 or 2 | 94 (77.0%) | 249 (71.3%) | 1.000 | 0.223 | 25 (49.0%) | 45 (26.8%) | 1.000 | 0.003* |

| 3, 4, or 5 | 28 (23.0%) | 100 (28.7%) | 1.348 (0.833-2.182) | 26 (51.0%) | 123 (73.2%) | 2.628 (1.377-5.017) | ||

| Clinical T stage | ||||||||

| 1 or 2 | 113 (92.6%) | 316 (90.5%) | 1.000 | 0.488 | 39 (76.5%) | 125 (74.4%) | 1.000 | 0.766 |

| 3 or 4 | 9 (7.4%) | 33 (9.5%) | 1.311 (0.608-2.825) | 12 (23.5%) | 43 (25.6%) | 1.118 (0.537-2.329) | ||

| Pathologic T stage | ||||||||

| 2 | 79 (64.8%) | 232 (66.5%) | 1.000 | 0.730 | 17 (33.3%) | 35 (20.8%) | 1.000 | 0.066 |

| 3 or 4 | 43 (35.2%) | 117 (33.5%) | 0.927 (0.601-1.428) | 34 (66.7%) | 133 (79.2%) | 1.900 (0.952-3.792) | ||

| Pathologic N stage | ||||||||

| N0 | 121 (99.2%) | 338 (96.8%) | 1.000 | 0.159 | 43 (84.3%) | 129 (76.8%) | 1.000 | 0.251 |

| N1 | 1 (0.8%) | 11 (3.2%) | 3.938 (0.503-30.823) | 8 (15.7%) | 39 (23.2%) | 1.625 (0.705-3.747) | ||

| Seminal vesicle invasion | ||||||||

| No | 110 (90.2%) | 316 (90.5%) | 1.000 | 0.902 | 31 (60.8%) | 86 (51.2%) | 1.000 | 0.229 |

| Yes | 12 (9.8%) | 33 (9.5%) | 0.957 (0.478-1.919) | 20 (39.2%) | 82 (48.8%) | 1.478 (0.781-2.798) | ||

| Perineural invasion | ||||||||

| No | 44 (36.1%) | 119 (34.1%) | 1.000 | 0.694 | 6 (11.8%) | 12 (7.1%) | 1.000 | 0.293 |

| Yes | 78 (63.9%) | 230 (65.9%) | 1.090 (0.709-1.677) | 45 (88.2%) | 156 (92.9%) | 1.733 (0.616-4.877) | ||

| Lymphovascular invasion | ||||||||

| No | 114 (93.4%) | 323 (92.6%) | 1.000 | 0.743 | 38 (74.5%) | 104 (61.9%) | 1.000 | 0.099 |

| Yes | 8 (6.6%) | 26 (7.4%) | 1.147 (0.505-2.606) | 13 (25.5%) | 64 (38.1%) | 1.799 (0.891-3.632) | ||

| D'Amico classification | ||||||||

| Low or intermediate risk | 68 (55.7%) | 198 (56.7%) | 1.000 | 0.849 | 18 (35.3%) | 57 (33.9%) | 1.000 | 0.857 |

| High risk | 54 (44.3%) | 151 (43.3%) | 0.960 (0.634-1.455) | 33 (64.7%) | 111 (66.1%) | 1.062 (0.551-2.049) | ||

ORs with their 95% CIs were estimated using logistic regression models. * p < 0.05 as statistically significant.

ORs (95% CIs) of clinical status and HNF1A rs2464196 genotypic frequencies in included patients with or without BCR.

| Variable | No BCR (n = 471) | BCR (n = 219) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GG (n = 124) | GA+AA (n = 347) | OR (95% CI) | p | GG (n = 53) | GA+AA (n = 166) | OR (95% CI) | p | |

| Pathologic Gleason grade group | ||||||||

| 1 or 2 | 96 (77.4%) | 247 (71.2%) | 1.000 | 0.180 | 25 (47.2%) | 45 (27.1%) | 1.000 | 0.006* |

| 3, 4, or 5 | 28 (22.6%) | 100 (28.8%) | 1.388 (0.858-2.245) | 28 (52.8%) | 121 (72.9%) | 2.401 (1.268-4.547) | ||

| Clinical T stage | ||||||||

| 1 or 2 | 115 (92.7%) | 314 (90.5%) | 1.000 | 0.450 | 41 (77.4%) | 123 (74.1%) | 1.000 | 0.634 |

| 3 or 4 | 9 (7.3%) | 33 (9.5%) | 1.343 (0.623-2.893) | 12 (22.6%) | 43 (25.9%) | 1.194 (0.575-2.481) | ||

| Pathologic T stage | ||||||||

| 2 | 80 (64.5%) | 231 (66.6%) | 1.000 | 0.678 | 17 (32.1%) | 35 (21.1%) | 1.000 | 0.102 |

| 3 or 4 | 44 (35.5%) | 116 (33.4%) | 0.913 (0.594-1.404) | 36 (67.9%) | 131 (78.9%) | 1.767 (0.889-3.513) | ||

| Pathologic N stage | ||||||||

| N0 | 123 (99.2%) | 336 (96.8%) | 1.000 | 0.152 | 45 (84.9%) | 127 (76.5%) | 1.000 | 0.195 |

| N1 | 1 (0.8%) | 11 (3.2%) | 4.027 (0.515-31.515) | 8 (15.1%) | 39 (23.5%) | 1.727 (0.751-3.974) | ||

| Seminal vesicle invasion | ||||||||

| No | 112 (90.3%) | 314 (90.5%) | 1.000 | 0.957 | 32 (60.4%) | 85 (51.2%) | 1.000 | 0.244 |

| Yes | 12 (9.7%) | 33 (9.5%) | 0.981 (0.490-1.965) | 21 (39.6%) | 81 (48.8%) | 1.452 (0.774-2.724) | ||

| Perineural invasion | ||||||||

| No | 45 (36.3%) | 118 (34.0%) | 1.000 | 0.646 | 6 (11.3%) | 12 (7.2%) | 1.000 | 0.345 |

| Yes | 79 (63.7%) | 229 (66.0%) | 1.105 (0.720-1.696) | 47 (88.7%) | 154 (92.8%) | 1.638 (0.583-4.603) | ||

| Lymphovascular invasion | ||||||||

| No | 116 (93.5%) | 321 (92.5%) | 1.000 | 0.701 | 39 (73.6%) | 103 (62.0%) | 1.000 | 0.126 |

| Yes | 8 (6.5%) | 26 (7.5%) | 1.174 (0.517-2.668) | 14 (26.4%) | 63 (38.0%) | 1.704 (0.858-3.385) | ||

| D'Amico classification | ||||||||

| Low or intermediate risk | 69 (55.6%) | 197 (56.8%) | 1.000 | 0.828 | 19 (35.8%) | 56 (33.7%) | 1.000 | 0.778 |

| High risk | 55 (44.4%) | 150 (43.2%) | 0.955 (0.632-1.444) | 34 (64.2%) | 110 (66.3%) | 1.098 (0.575-2.096) | ||

ORs with their 95% CIs were estimated using logistic regression models. * p < 0.05 as statistically significant.

Correlation between HNF1A expression and clinical features in patients with PCa based on TCGA-PRAD data. (A) HNF1A expression levels in unpaired normal and tumor tissues in the TCGA-PRAD dataset are presented. (B) HNF1A expression levels were analyzed in 52 matched PCa tissues and their corresponding normal tissues. (C-E) HNF1A expression levels in PCa from TCGA-PRAD were compared based on the Gleason scores (C), pathological T stages (D), and distant metastasis (E). (F) Kaplan-Meier survival curves were used to illustrate OS of patients with high and low HNF1A expression.

HNF1A-associated pathways in patients with PCa. The horizontal bar plot displays pathways identified in the Hallmark database that are correlated with HNF1A expression. Pathways positively and negatively associated with HNF1A are displayed in red and blue, respectively. The x-axis indicates normalized enrichment scores (NESs).

Discussion

PCa is generally treatable when detected early and monitored closely. However, advanced-stage PCa tumors frequently acquire resistance to ADT, which results in progression to CRPC, a lethal form of PCa [28, 29]. Given the oncogenic role of the transcription factor HNF1A in PCa progression [13-15], we examined missense and intronic SNPs within HNF1A in relation to BCR. Distinct SNP distributions were observed between patients with and without BCR. In particular, carriers of the mutant C allele of rs735396 and rs1169288 or the mutant A allele of rs2464196 exhibited a significantly elevated risk of PCa tumors with higher Gleason grades under a dominant model (TC+CC, AC+CC, or GA+AA). These associations, particularly for rs735396 and rs2464196, were more pronounced in patients with BCR than in those without. In addition, the analysis of PCa tissue samples revealed that elevated HNF1A expression was significantly correlated with higher pathological Gleason scores, larger tumor sizes, and tumor metastasis, as well as enrichment of pathways related to MYC and E2F targets. Taken together, these findings suggest that HNF1A genetic variants and expression may jointly contribute to PCa progression and aggressiveness.

Inflammation has been increasingly recognized as a critical factor in the pathogenesis and progression of many solid tumors, including PCa [30]. C-reactive protein (CRP), an inflammation marker and acute-phase protein produced in response to inflammation, is correlated with tumor progression and prognosis in several cancers, including PCa [31-33]. Patients with PCa with adverse pathological features (e.g., high Gleason scores, extracapsular extension, seminal vesicle invasion, lymph node metastasis, and positive surgical margins) demonstrate elevated preoperative CRP levels. Furthermore, patients with PCa with elevated CRP levels have significantly lower 5-year BCR-free survival rates than do those with normal CRP levels [34].

HNF1A, mainly expressed in the liver, acts as a transcription factor. CRP is also primarily synthesized in the liver by hepatocytes [35]. Thus, HNF1A may serve as a crucial regulator of CRP production. Contemporary evidence has confirmed that HNF1A binds to the promoter region of CRP, thereby upregulating CRP expression and promoting laryngeal cancer progression [36]. Moreover, genome-wide association studies have identified several HNF1A genetic variants, including rs735396, rs1169288, and rs2464196, that are associated with circulating CRP levels [37, 38]. Taken together, these findings suggest that rs735396, rs1169288, and rs2464196 regulate HNF1A expression, thereby influencing CRP levels and ultimately affecting surgical Gleason scores. Similar to those with PCa, patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) harboring the AA genotype of rs2464196 demonstrate significantly elevated AFP, AST, and ALT levels, which promote HCC progression [17, 18].

rs1169288 and rs2464196 are nonsynonymous coding variants, also called missense SNPs, located in the exonic regions of HNF1A. A missense SNP can alter the amino acid sequence of the encoded protein, potentially affecting the protein's stability and its ability to interact with other molecules [39, 40]. Thus, we hypothesize that rs1169288 and rs2464196 influence the structure of HNF1A, thereby enhancing its binding to the CRP promoter, upregulating CRP expression, and ultimately exacerbating PCa aggressiveness; this hypothesis requires validation in future studies. In contrast to rs1169288 and rs2464196, rs735396 is located within intron 9 of HNF1A. Polymorphisms in intronic regions do not typically alter the protein sequence. Nevertheless, emerging evidence indicates that these types of variations may influence cancer susceptibility through both genetic and epigenetic mechanisms. Intronic sequences often harbor cis-acting regulatory elements, such as transcription factor binding sites, enhancers, and silencers, all of which can positively or negatively regulate gene expression [41]. Jiang et al. proposed that rs735396 might reside within an enhancer element, where this SNP could affect interactions with DNA-binding factors and thereby regulate HNF1A expression. They further demonstrated that the T allele may reduce HNF1A expression by altering enhancer activity in HCC cells [42]. Nevertheless, the impact of rs735396 on HNF1A expression in PCa cells remains to be elucidated in future studies.

It is well documented that PCa tumor foci exhibit marked overexpression of MYC mRNA and protein, which correlates with increased disease severity, including higher Gleason scores, BCR, and metastasis [43, 44]. Moreover, MYC overexpression in normal luminal cells of the murine prostate is sufficient to initiate PCa [45]. Taken together, these findings demonstrate that MYC is an oncogene that is a substantial driver of tumorigenesis and progression in PCa. In the current study, we noted that HNF1A expression was positively associated with MYC target gene-related signatures in the TCGA-PRAD dataset. Several studies have reported that MYC transcriptionally activates the long noncoding RNA HNF1A-AS1, promoting progression in various cancers [46, 47]. HNF1A can activate HNF1A-AS1 transcription by directly binding to its promoter region in HCC [48]. Therefore, HNF1A may cooperate with MYC to promote PCa progression by regulating HNF1A-AS1; however, this hypothesis requires further investigation. E2F transcription factors are implicated in PCa because they are strongly expressed in tumors and promote cancer cell growth by regulating the cell cycle and other cellular processes. Higher expression of specific E2F members (E2F1-3) is associated with more advanced tumors, higher Gleason scores, and increased posttreatment BCR risk [27]. We also observed that HNF1A expression was associated with E2F target gene-related signatures in the TCGA-PRAD dataset. Research indicates that MYC induces the transcription of E2F1-3 genes [49], suggesting that MYC-regulated E2F expression is involved in HNF1A-mediated PCa progression. However, the interactions among HNF1A, MYC, and E2F in PCa progression warrant further investigation.

In summary, this is the first study to investigate the distinct allelic effects of both missense and intronic HNF1A SNPs in a Taiwanese population, highlighting their potential roles in PCa progression. Clinically, we identified an oncogenic role of HNF1A in PCa specimens. Moreover, our findings indicate that HNF1A-related signaling pathways, including MYC and E2F targets, may be key drivers of PCa progression. SNP profiling of noninvasive biopsies to predict cancer risk and disease progression can provide valuable insights for precision medicine. In particular, the missense SNPs rs2464196 (S487N) and rs1169288 (I27L), along with the intronic SNP rs735396, may serve as critical markers of PCa aggressiveness, particularly in patients with BCR.

However, our study still has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, all PCa patients included in the SNP analysis were Taiwanese (of Asian ethnicity), whereas the correlations between HNF1A expression and clinicopathologic features or prognosis were assessed using the TCGA-PRAD dataset, which is composed predominantly of Caucasian and African American individuals. Therefore, additional studies are required to validate the associations between HNF1A expression and clinicopathologic characteristics specifically in Taiwanese PCa tissues. Second, future investigations should simultaneously collect both mRNA and DNA from the same PCa patient samples to better assess the impact of HNF1A SNPs on gene expression. Finally, whether the missense SNPs rs2464196 and rs1169288, as well as the intronic SNP rs735396, can serve as reliable markers for predicting PCa aggressiveness should be further examined across diverse racial and ethnic populations.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This research was supported by the TMU Research Center of Cancer Translational Medicine under the Featured Areas Research Center Program, funded by the Higher Education Sprout Project of the Ministry of Education, Taiwan (grant to M.-H. Chien), and Taipei Medical University-Wan Fang Hospital (grant no. 114-wf-swf-01; grant to Y.-C. Wen).

Ethics approval

All experiments involving clinical samples were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Taichung Veterans General Hospital (IRB no. CE19062A-2).

Data availability statement

The data supporting the current findings are included within the article. Additional original data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing Interests

The authors have declared that no competing interest exists.

References

1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Wagle NS, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023;73:17-48

2. Litwin MS, Tan HJ. The Diagnosis and Treatment of Prostate Cancer: A Review. JAMA. 2017;317:2532-42

3. Brockman JA, Alanee S, Vickers AJ, Scardino PT, Wood DP, Kibel AS. et al. Nomogram Predicting Prostate Cancer-specific Mortality for Men with Biochemical Recurrence After Radical Prostatectomy. Eur Urol. 2015;67:1160-7

4. Khoshkar Y, Westerberg M, Adolfsson J, Bill-Axelson A, Olsson H, Eklund M. et al. Mortality in men with castration-resistant prostate cancer-A long-term follow-up of a population-based real-world cohort. BJUI Compass. 2022;3:173-83

5. Hashimoto T, Nakashima J, Kashima T, Yamaguchi Y, Satake N, Nakagami Y. et al. Predicting factors for progression to castration resistance prostate cancer after biochemical recurrence in patients with clinically localized prostate cancer who underwent radical prostatectomy. Int J Clin Oncol. 2020;25:1704-10

6. Nishino T, Yamamoto S, Numao N, Komai Y, Oguchi T, Yasuda Y. et al. Predictors of Progression to Castration-resistant Prostate Cancer After Radical Prostatectomy in High-risk Prostate Cancer Patients. Cancer Diagn Progn. 2024;4:646-51

7. Lau HH, Ng NHJ, Loo LSW, Jasmen JB, Teo AKK. The molecular functions of hepatocyte nuclear factors - In and beyond the liver. J Hepatol. 2018;68:1033-48

8. Abel EV, Goto M, Magnuson B, Abraham S, Ramanathan N, Hotaling E. et al. HNF1A is a novel oncogene that regulates human pancreatic cancer stem cell properties. Elife. 2018;7:e33947

9. Zou N, Zhang X, Li S, Li Y, Zhao Y, Yang X. et al. Elevated HNF1A expression promotes radiation-resistance via driving PI3K/AKT signaling pathway in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma cells. J Cancer. 2021;12:5013-24

10. Hu Y, Wu F, Liu Y, Zhao Q, Tang H. DNMT1 recruited by EZH2-mediated silencing of miR-484 contributes to the malignancy of cervical cancer cells through MMP14 and HNF1A. Clin Epigenetics. 2019;11:186

11. Lu Y, Xu D, Peng J, Luo Z, Chen C, Chen Y. et al. HNF1A inhibition induces the resistance of pancreatic cancer cells to gemcitabine by targeting ABCB1. EBioMedicine. 2019;44:403-18

12. Takashima Y, Horisawa K, Udono M, Ohkawa Y, Suzuki A. Prolonged inhibition of hepatocellular carcinoma cell proliferation by combinatorial expression of defined transcription factors. Cancer Sci. 2018;109:3543-53

13. Shukla S, Cyrta J, Murphy DA, Walczak EG, Ran L, Agrawal P. et al. Aberrant Activation of a Gastrointestinal Transcriptional Circuit in Prostate Cancer Mediates Castration Resistance. Cancer Cell. 2017;32:792-806.e797

14. Senatorov IS, Bowman J, Jansson KH, Alilin AN, Capaldo BJ, Lake R. et al. Castrate-resistant prostate cancer response to taxane is determined by an HNF1-dependent apoptosis resistance circuit. Cell Rep Med. 2024;5:101868

15. Shukla S, Li D, Cho WH, Schoeps DM, Nguyen HM, Conner JL. et al. BET inhibitors reduce tumor growth in preclinical models of gastrointestinal gene signature-positive castration-resistant prostate cancer. J Clin Invest. 2025;135:e180378

16. Zhang E, Huang X, He J. Integrated bioinformatic analysis of HNF1A in human cancers. J Int Med Res. 2021;49:300060521997326

17. Bedira IS, Sayed IETE, Hendy OM, Abdel-Samiee M, Rashad AM, Zaid AB. Hepatocyte nuclear factor 1 alpha variants as risk factor for hepatocellular carcinoma development with and without diabetes mellitus. Gene Reports. 2024;37:102078

18. Bedair HM, Sayed IETE, Hendy OM, Abdel-Samiee M, Sayad IAEHE, Mandour SS. The hepatocyte nuclear factor 1 homeobox A (HNF1A) gene polymorphism and AFP serum levels in Egyptian HCC patients. Egyptian Liver J. 2024;14:89

19. Labriet A, De Mattia E, Cecchin E, Lévesque É, Jonker D, Couture F. et al. Improved Progression-Free Survival in Irinotecan-Treated Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Patients Carrying the HNF1A Coding Variant p.I27L. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:712

20. Dallali H, Hechmi M, Morjane I, Elouej S, Jmel H, Ben Halima Y. et al. Association of HNF1A gene variants and haplotypes with metabolic syndrome: a case-control study in the Tunisian population and a meta-analysis. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2022;14:25

21. Zhou YJ, Yin RX, Hong SC, Yang Q, Cao XL, Chen WX. Association of the HNF1A polymorphisms and serum lipid traits, the risk of coronary artery disease and ischemic stroke. J Gene Med. 2017;19:e2941

22. Morjane I, Kefi R, Charoute H, Lakbakbi El Yaagoubi F, Hechmi M. et al. Association study of HNF1A polymorphisms with metabolic syndrome in the Moroccan population. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2017;11(Suppl 2):S853-7

23. Lin YW, Wang SS, Wen YC, Tung MC, Lee LM, Yang SF. et al. Genetic Variations of Melatonin Receptor Type 1A are Associated with the Clinicopathologic Development of Urothelial Cell Carcinoma. Int J Med Sci. 2017;14:1130-5

24. Koupparis AJ, Grummet JP, Hurtado-Coll A, Bell RH, Buchan N, Goldenberg SL. et al. Radical prostatectomy for high-risk clinically localized prostate cancer: a prospective single institution series. Can Urol Assoc J. 2011;5:E156-61

25. Qiu X, Boufaied N, Hallal T, Feit A, de Polo A, Luoma AM. et al. MYC drives aggressive prostate cancer by disrupting transcriptional pause release at androgen receptor targets. Nat Commun. 2022;13:2559

26. Arriaga JM, Panja S, Alshalalfa M, Zhao J, Zou M, Giacobbe A. et al. A MYC and RAS co-activation signature in localized prostate cancer drives bone metastasis and castration resistance. Nat Cancer. 2020;1:1082-96

27. Han Z, Mo R, Cai S, Feng Y, Tang Z, Ye J. et al. Differential Expression of E2F Transcription Factors and Their Functional and Prognostic Roles in Human Prostate Cancer. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2022;10:831329

28. Shore N. Management of early-stage prostate cancer. Am J Manag Care. 2014;20:S260-72

29. Harris WP, Mostaghel EA, Nelson PS, Montgomery B. Androgen deprivation therapy: progress in understanding mechanisms of resistance and optimizing androgen depletion. Nat Clin Pract Urol. 2009;6:76-85

30. Sharma U, Sahu A, Shekhar H, Sharma B, Haque S, Kaur D. et al. The heat of the battle: inflammation's role in prostate cancer development and inflammation-targeted therapies. Discov Oncol. 2025;16:108

31. Lehrer S, Diamond EJ, Mamkine B, Droller MJ, Stone NN, Stock RG. C-reactive protein is significantly associated with prostate-specific antigen and metastatic disease in prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2005;95:961-2

32. Nozoe T, Saeki H, Sugimachi K. Significance of preoperative elevation of serum C-reactive protein as an indicator of prognosis in esophageal carcinoma. Am J Surg. 2001;182:197-201

33. Liao DW, Hu X, Wang Y, Yang ZQ, Li X. C-reactive Protein Is a Predictor of Prognosis of Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2020;50:161-71

34. Sevcenco S, Mathieu R, Baltzer P, Klatte T, Fajkovic H, Seitz C. et al. The prognostic role of preoperative serum C-reactive protein in predicting the biochemical recurrence in patients treated with radical prostatectomy. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2016;19:163-7

35. Black S, Kushner I, Samols D. C-reactive Protein. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:48487-90

36. Zhao Z, Zhu X, Xu J, Song P, Sun Y, Yang Z. et al. CRP and HNF1A collaborate to regulate the progression of laryngeal cancer through the Wnt signaling pathway. Funct Integr Genomics. 2025;25:160

37. Reiner AP, Barber MJ, Guan Y, Ridker PM, Lange LA, Chasman DI. et al. Polymorphisms of the HNF1A gene encoding hepatocyte nuclear factor-1 alpha are associated with C-reactive protein. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:1193-201

38. Ridker PM, Pare G, Parker A, Zee RY, Danik JS, Buring JE. et al. Loci related to metabolic-syndrome pathways including LEPR,HNF1A, IL6R, and GCKR associate with plasma C-reactive protein: the Women's Genome Health Study. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:1185-92

39. Dobson RJ, Munroe PB, Caulfield MJ, Saqi MA. Predicting deleterious nsSNPs: an analysis of sequence and structural attributes. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:217

40. Kucukkal TG, Petukh M, Li L, Alexov E. Structural and physico-chemical effects of disease and non-disease nsSNPs on proteins. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2015;32:18-24

41. Deng N, Zhou H, Fan H, Yuan Y. Single nucleotide polymorphisms and cancer susceptibility. Oncotarget. 2017;8:110635-49

42. Jiang MM, Gu X, Yang J, Wang MM, Li HM, Fang M. et al. Association of a functional intronic polymorphism rs735396 in HNF1A gene with the susceptibility to hepatocellular carcinoma in Han Chinese population. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2017;10:671-9

43. Hawksworth D, Ravindranath L, Chen Y, Furusato B, Sesterhenn IA, McLeod DG. et al. Overexpression of C-MYC oncogene in prostate cancer predicts biochemical recurrence. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2010;13:311-5

44. Yu C, Wu G, Dang N, Zhang W, Zhang R, Yan W. et al. Inhibition of N-myc downstream-regulated gene 2 in prostatic carcinoma. Cancer Biol Ther. 2011;12:304-13

45. Ellwood-Yen K, Graeber TG, Wongvipat J, Iruela-Arispe ML, Zhang J, Matusik R. et al. Myc-driven murine prostate cancer shares molecular features with human prostate tumors. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:223-38

46. Zhao R, Guo X, Zhang G, Liu S, Ma R, Wang M. et al. CMYC-initiated HNF1A-AS1 overexpression maintains the stemness of gastric cancer cells. Cell Death Dis. 2024;15:288

47. Wu J, Li R, Li L, Gu Y, Zhan H, Zhou C. et al. MYC-activated lncRNA HNF1A-AS1 overexpression facilitates glioma progression via cooperating with miR-32-5p/SOX4 axis. Cancer Med. 2020;9:6387-98

48. Ding CH, Yin C, Chen SJ, Wen LZ, Ding K, Lei SJ. et al. The HNF1α-regulated lncRNA HNF1A-AS1 reverses the malignancy of hepatocellular carcinoma by enhancing the phosphatase activity of SHP-1. Mol Cancer. 2018;17:63

49. Leone G, Sears R, Huang E, Rempel R, Nuckolls F, Park CH. et al. Myc requires distinct E2F activities to induce S phase and apoptosis. Mol Cell. 2001;8:105-13

Author contact

![]() Corresponding authors: ysfedu.tw (S.-F.Y.); d002089002edu.tw (M.-H.C.); Tel.: +886-4-24739595 (ext. 34253) (S.-F.Y.); +886-2-27361661 (ext. 3237) (M.-H.C.); Fax: +886-4-24723229 (S.-F.Y.); +886-2-27390500 (M.-H.C.).

Corresponding authors: ysfedu.tw (S.-F.Y.); d002089002edu.tw (M.-H.C.); Tel.: +886-4-24739595 (ext. 34253) (S.-F.Y.); +886-2-27361661 (ext. 3237) (M.-H.C.); Fax: +886-4-24723229 (S.-F.Y.); +886-2-27390500 (M.-H.C.).

Global reach, higher impact

Global reach, higher impact