Impact Factor

ISSN: 1449-1907

Int J Med Sci 2026; 23(2):428-442. doi:10.7150/ijms.116432 This issue Cite

Review

Bioengineering modification and application of bacterial outer membrane vesicles

1. Department of Laboratory Medicine, Peking University Third Hospital, Beijing 100191, China.

2. Department of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Peking University Third Hospital, Beijing 100191, China.

# These authors contribute equally to this work

Received 2025-4-25; Accepted 2025-11-27; Published 2026-1-1

Abstract

Outer Membrane Vesicles (OMVs) are spherical nanovesicles naturally secreted by Gram-negative bacteria, playing key roles in nutrient uptake, toxin delivery, and the transmission of drug resistance. Recent studies have increasingly focused on the clinical potential of OMVs. Due to their remarkable biocompatibility and immunogenic properties, OMVs offer wide-ranging applications in vaccine development and antigen/drug delivery, showing great promise in the treatment of tumors, autoimmune diseases, and infections. However, challenges remain in standardizing the production and modification of OMVs, limiting their broader application. This review consolidates research on OMV modification and application, aiming to provide valuable insights to advance the development of OMV-based therapeutic strategies and clinical implementations.

Keywords: OMVs, bioengineering modifications, clinical applications

1. General introduction to OMVs

1.1 The biogenesis of OMVs

Outer Membrane Vesicles (OMVs) are spherical nanovesicles naturally derived from Gram-negative bacteria, with sizes ranging from 20 to 250 nm. Their biogenesis is a complex and multifactorial process, and no single or universal mechanism fully explains their production. Existing studies suggest that OMV production can be divided into two primary categories: one involves vesicle formation through outer membrane budding in living cells, and the other arises from the aggregation of membrane fragments after cell lysis, which subsequently form OMVs. The former involves several biogenesis mechanisms, including the reduction of localized outer membrane-peptidoglycan junctions, the accumulation of periplasmic contents, and increased outer membrane curvature.

The formation of OMVs is closely linked to the interaction between the outer membrane and the peptidoglycan layer. Under normal conditions, the outer membrane and peptidoglycan are connected by proteins such as Braun's lipoprotein (Lpp), outer membrane protein A (OmpA), and components of the Tol-Pal complex, which maintain membrane stability[1][2][3]. When these connections are weakened or disrupted, the outer membrane bulges outward, leading to the production and release of OMVs. In addition to changes in membrane crosslinking, the accumulation of periplasmic contents also plays a pivotal role in triggering OMV formation. Peptidoglycan fragments or misfolded proteins in the periplasmic space exert pressure on the outer membrane, promoting vesicle production[4]. Moreover, increased outer membrane curvature facilitates OMV formation. The insertion of foreign signaling molecules into the outer membrane alters its charge balance, causing membrane bending, which leads to OMV formation, as explained by the Bilayer-Couple Model[5].

Beyond vesicles from living bacteria, OMVs have also been identified in dead bacteria. A study by Cynthia B. et al. demonstrated that explosive cytolysis contributes to OMV formation. In their study, DNA damage in Pseudomonas aeruginosa induced the expression of phage-encoded endolysin, which degrades the peptidoglycan cell wall. This degradation causes cell rupture, and the resulting membrane fragments aggregate and assemble into OMVs[6].

1.2 The composition and function of OMVs

OMVs are loaded with a diverse array of substances, including outer membrane proteins, periplasmic proteins, cytoplasmic proteins, lipopolysaccharides (LPS), phospholipids, peptidoglycan, nucleic acids, and virulence factors, with proteins and phospholipids being key components. MS-based proteomic analysis of OMVs from Gram-negative bacteria has identified hundreds of vesicle proteins[7]. The protein composition of OMVs is influenced by various factors. For instance, OMVs released by different biogenesis mechanisms in P. aeruginosa exhibit significant variations in protein composition[8]. The protein composition of OMVs from Helicobacter pylori also varies markedly under different pH growth conditions[9]. Phospholipids are key structural components of OMVs, and their types and proportions differ across bacterial species. OMVs from Escherichia coli ETEC are enriched in phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), phosphatidylglycerol (PG), and cardiolipin (CL), while OMVs from Actinomycetes contain high concentrations of CL and PE, P. aeruginosa OMVs contain predominantly PG, and Haemophilus influenzae OMVs are mainly composed of PE[10].

OMVs are functionally diverse and play significant roles in nutrient uptake, stress response, biofilm formation, toxin delivery, and modulation of the host immune response. Firstly, OMVs carry hydrolytic enzymes and receptors that facilitate nutrient uptake. A study by Elhenawy et al. demonstrated that acid glycosidases and proteases are preferentially packaged into OMVs from Bacteroides, enhancing nutrient acquisition for the bacterial community[11]. Similarly, Ganeshwari Dhurve et al. found that OMVs from Acinetobacter baumannii DS002 were enriched in TonB-dependent transporter proteins (TonR), which are involved in the transport of iron complexes, including catecholates, hydroxamates, and hybrid iron carriers[12]. Secondly, vesiculation serves as a periplasmic stress response, where the release of OMVs is increased in reaction to stressors, thereby aiding bacterial survival in hostile environments. OMVs also play a vital role in biofilm formation. For example, Pseudomonas quinolone signals (PQS) released by P. aeruginosa are packaged within OMVs, which regulate biofilm formation and structure[13]. Furthermore, OMVs carry various virulence factors, including β-lactamase, alkaline phosphatase, lysophospholipase C, and Cycle-inhibiting factors (Cifs), which help bacteria invade host cells and modulate the host immune response, thereby promoting bacterial survival and replication[14].

1.3 The biological properties of OMVs

Compared to traditional drug carriers, OMVs offer excellent biocompatibility and stability, which help maintain drug stability and reduce leakage during long-distance delivery in vivo. Eilien Schulz and colleagues demonstrated that OMVs are biocompatible with epithelial cells and differentiated macrophages, maintaining inherent stability under storage conditions at 4 °C, -20 °C, -80 °C, and in freeze-dried form[15]. Additionally, OMVs possess adhesins on their surface, allowing them to be recognized and endocytosed by specific cells without the need for external targeting ligands. For example, OMVs from Salmonella and Shigella contain adhesins that facilitate their recognition and endocytosis by gastrointestinal cells. This inherent targeting ability provides a natural advantage in drug delivery, particularly to specific tissues or cell types. OMVs can efficiently deliver drugs to the target site, enhancing therapeutic efficacy and reducing side effects. Another notable feature of OMVs is their immunogenicity. OMVs are rich in Pathogen-Associated Molecular Patterns (PAMPs), including LPS, peptidoglycans, lipoproteins, and flagella, which strongly stimulate the innate immune system, promoting antigen presentation and T-cell activation. The nanoscale size of OMVs further facilitates their recognition and uptake by antigen-presenting cells (APCs)[16].

2. The bioengineering of OMVs

OMVs, derived from their parent cells, are rich in proteins, nucleic acids, and lipids, exhibiting exceptional biocompatibility, membrane stability, immunogenicity, safety, permeability, and tumor-targeting capabilities. Extensive research has affirmed the safety, stability, and permeability of OMVs, highlighting their potential in bioengineering. To harness OMVs for clinical applications, innovative modification strategies have been developed, mainly focusing on altering their cargo and membrane composition to enhance immunogenicity and tumor-targeting properties[18]. Numerous therapeutic and modification platforms based on OMVs have been established, showing their versatility in treating cancer, autoimmune diseases, and infectious diseases. Both modified and naturally occurring OMVs hold significant clinical therapeutic value[19]. OMV engineering strategies can be broadly categorized into three areas: gene editing, functional molecule loading, and surface modification.

2.1 Genetic engineering of OMVs

Genetic engineering primarily involves modifying the parental bacteria to program OMVs. Some studies have employed gene silencing through small interfering RNA (siRNA) in both in vivo and in vitro settings, or used CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene knockout to reduce or eliminate specific OMV components[20][21]. Moreover, since OMVs can be secreted even under conditions of outer membrane protein deficiency, knocking out the ompA gene, which encodes outer membrane proteins, can significantly enhance OMV yield. These modified OMVs show improved electron transfer efficiency in Fe(III) reduction, dye degradation, and bioelectrochemical system (BES) current generation, potentially facilitating the incorporation of cargo beneficial for electron transfer and biofilm formation, such as c-type cytochromes, functional proteins, eDNA, polysaccharides, and signaling molecules[22].

Conversely, the overexpression or introduction of certain genes can bestow OMVs with new immunogenic properties, enhance their targeting capabilities, or enable the loading of specific functional substances. For example, genetically programmed OMVs with surface modifications, such as the insertion of the extracellular domain of programmed death 1 (PD1), represent a novel and effective immunotherapeutic agent. This genetic modification does not compromise OMVs' ability to trigger immune activation. Moreover, engineered OMV-PD1 can bind to PD-L1 on tumor cell surfaces, promoting internalization and degradation, thereby protecting T cells from the PD1/PD-L1 immune suppression axis[23].

2.2 Functional molecular loading of OMVs

OMVs, with their superior biocompatibility and targeting capabilities, have been utilized as carriers and vaccines. By loading functional molecules such as enzymes, antibiotics, and nucleic acids, and exploiting the exceptional targeting properties of OMVs, it is possible to regulate cellular activities and the survival environment. OMVs derived from attenuated Klebsiella pneumoniae or E. coli are commonly used for tumor drug loading. These OMVs not only act as biological nanocarriers for chemotherapeutic agents but also elicit appropriate immune responses, making them promising candidates for tumor chemoimmunotherapy[24][31].

Current drug-loading methods include incubation, extrusion, and sonication[26][27]. However, antibiotic loading is more distinctive. Given that bacteria can eliminate antibiotics by secreting OMVs—a mechanism contributing to antimicrobial drug resistance—antibiotics may be encapsulated within OMVs when bacteria secrete them in the presence of antibiotics[28]. Additionally, due to the phospholipid composition of OMV membranes, liposome wrapping has been used to transport hydrophilic drugs like doxorubicin (DOX) into OMVs[29][30]. As natural nanocarriers, OMVs possess a mechanically stable bilayer structure, conferring excellent biostability. Antibiotic-loaded OMVs retain most of the native adjuvant components derived from their parent bacteria. These components promote immune maturation, induce controlled inflammatory responses, and enhance the immunogenicity of the tumor microenvironment. This mechanism not only recruits macrophages but may also synergize with the encapsulated antibiotics[30][31].

OMVs loaded with nucleic acids hold significant potential for various applications, offering enhanced safety and substantial cargo capacity, making them effective genetic engineering tools[32]. Current bacterial modification methods for nucleic acid delivery include engineering attenuated strains, lysis circuits, and conjugation mechanisms[33][34][35]. OMVs can also benefit the development of autonomous nanorobots, which are advanced precision therapeutic tools. Traditional nanorobot designs rely primarily on inorganic materials, which often have poor biocompatibility and limited biological functionality. This has prompted exploration of OMVs in nanorobotics[36]. Nanorobots surface-engineered with cell-penetrating peptides leverage OMV membrane properties to promote tumor targeting and penetration, effectively protecting the loaded gene-silencing tool siRNA from enzymatic degradation, thus enhancing siRNA delivery and immune stimulation[37].

Despite current advancements, the drug-loading concentration in OMVs remains insufficient due to the barrier posed by the vesicle membrane. Additionally, the lack of standardized clinical production and enrichment methods for OMVs limits their broader application. While safety has largely been validated, OMVs derived from pathogenic bacteria may still contain residual endotoxins and other harmful components that are difficult to remove, potentially leading to side effects in clinical applications[28]. Further research is needed to develop effective, standardized methods for OMV production, enrichment, and endotoxin removal.

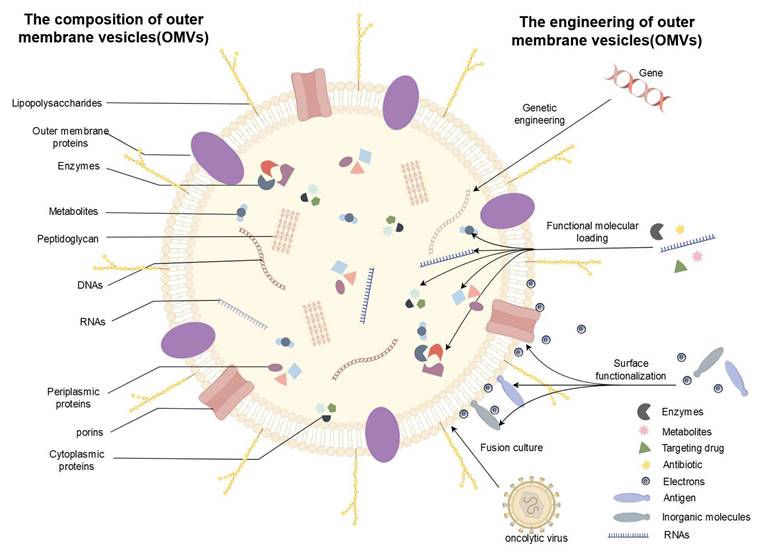

The composition and bioengineering of OMVs. OMVs, primarily composed of bacterial outer membranes, periplasmic space, and cytoplasmic content, demonstrate exceptional potential for bioengineering. (1) Genetic Engineering: The yield and components of OMVs can be modified by knocking out or introducing specific genes. (2) Functional Molecular Loading: By loading functional molecules such as enzymes, antibiotics, and nucleic acids, and leveraging the unique targeting properties of OMVs, cellular activities and the survival environment can be regulated. (3) Surface Functionalization: Surface modification using antigens, inorganic molecules, and electrons offers promising solutions to challenges hindering the clinical translation of OMVs, enhancing their biocompatibility and permeability. (4) Auxiliary Modification: Utilizing fusion culture and other auxiliary modifications to adjust the composition of OMVs plays a pivotal role in enhancing their properties. (By Figdraw).

2.3 Surface functionalization of OMVs

The surface of OMVs exhibits exceptional plasticity, and modifications can enhance their biocompatibility and permeability. For instance, Li-Hua Peng et al. employed an αvβ3 integrin-targeting ligand and indocyanine green to modify OMVs derived from genetically engineered E. coli, demonstrating superior penetration of the stratum corneum and increased specificity toward melanoma[38]. OMVs also possess notable immunogenicity, with the specific presentation of antigens on their surface capable of triggering targeted anti-tumor immune responses, making them valuable for cancer treatment. The potential of genetically modified OMVs, such as those with the extracellular domain of PD1 inserted, has been successfully validated[23][39][40]. Recently, Keman Cheng et al. developed a multifunctional OMV-based platform, displaying tumor antigens on the OMV surface by fusing them with ClyA protein. This process, streamlined by a Plug-and-Design system using a tag/capture protein pair, enables OMVs modified with various protein capture agents to simultaneously display multiple tumor antigens, eliciting synergistic anti-tumor immune responses[41]. Additionally, the surface charge of OMVs plays a critical role in their modification. One study revealed that the activation of immune responses by OMVs is inversely related to their surface positive charge, which has important implications for OMV surface engineering[42].

Surface modification presents a promising solution to many challenges limiting the clinical translation of OMVs. Protein expression bottlenecks and difficulties in localizing antigens to the host cell's outer membrane can make antigen display on OMVs unpredictable, particularly for bulky or complex antigens, significantly reducing the efficacy of OMV-based vaccines. To address this, a study proposed biotinylating surface antigens on OMVs. Kevin B. Weyant and colleagues developed a modular platform to link biotinylated antigens to the OMV exterior. They demonstrated that OMVs could be easily modified with a wide range of biotinylated subunit antigens, including globular and membrane proteins, glycans, glycoconjugates, haptens, lipids, and short peptides. When these OMV formulations were injected into mice, a robust antigen-specific antibody response was observed, highlighting a significant improvement in the immunogenicity and specificity of OMV-based vaccines[43].

Systemic toxicity caused by PAMPs in OMVs is a significant barrier to their clinical translation, as the specific presentation of antigens on the OMV surface to trigger targeted anti-tumor immune responses can lead to toxic side effects. This issue can be mitigated through surface mineralization. Xue Chen et al. coated melanin-loaded OMVs (OMVMel) with calcium phosphate (CaP) via surface mineralization to create OMVMel@CaP. Compared to OMVMel, OMVMel@CaP exhibited reduced systemic inflammatory responses and less damage to the liver, spleen, lungs, and kidneys, allowing for increased dosage to enhance anti-tumor effects. In the acidic tumor microenvironment, the CaP shell decomposes, releasing OMVMel and triggering anti-tumor immune responses. The dual stimulation from OMVs as immune adjuvants and DAMPs released through photothermal effects significantly improved tumor treatment efficiency by promoting the infiltration of mature dendritic cells (DCs), M1 macrophages, and activated CD8+ T cells, while reducing the proportion of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) in tumors[44]. Similarly, anchoring OMVs with Fe2+ through electrostatic interactions and loading them with the STING agonist-4, followed by tumor-targeting DSPE-PEG-FA modification, functionalized the OMVs. This approach enhanced tumor-targeting capabilities, achieved tumor-specific therapy, and minimized side effects[45][46].

Surface modification of OMVs has been widely applied in the development of personalized tumor vaccines, enhancing both their safety and immunogenicity. However, surface-modified OMVs still face challenges in clinical applications due to the lack of standardized production methods, limited effectiveness, and high modification costs. To fully realize their clinical potential, significant obstacles related to efficacy and large-scale production must be addressed[47][48][49]. Lipid nanoparticles and synthetic liposomes (including modern LNPs for mRNA delivery) are highly tunable in composition, surface chemistry, and cargo loading, with well-established, scalable GMP manufacturing routes that ensure reproducible stability, controlled pharmacokinetics, and reduced innate immune activation unless deliberately engineered otherwise. Hybrid strategies that combine OMV-like biological cues with the tunability and stability of synthetic lipid platforms are emerging as a promising approach to capture the benefits of both systems[50][51][52].

2.4 Auxiliary modification of OMVs

Fusion culture is an emerging specialized cultivation method that combines OMVs with other biological entities and products to enhance their tumor immune effects. Current research has primarily focused on oncolytic viruses. Oncolytic viruses cultivated in fusion with mineralized OMVs have demonstrated prolonged drug circulation times and enhanced immune responses in mouse models[53][54]. However, this technology requires higher viral titers, significantly increasing the cost and complexity of modification. Therefore, future research should concentrate on downstream processing techniques for oncolytic viruses and purification methods for OMVs to improve their clinical applicability[55]. Macrophage membrane vesicles (MMVs) represent another promising material for integrated cultivation. MMVs not only synergize with OMVs to induce a robust immune response but also neutralize endotoxins in OMVs, enhancing their safety. This approach has shown favorable therapeutic outcomes in a mouse model of sepsis caused by P. aeruginosa infection. Further experiments with human-derived macrophages are necessary to validate its safety and efficacy[56].

Moreover, cultivation under specific environments can modulate the properties of OMVs by influencing gene expression. One study found that serum-induced OMVs in the mosquito gut contained serum-derived lipids, such as phosphatidylcholine. These OMVs selectively targeted parasites, rendering mosquitoes resistant to Plasmodium infection, which offers a potential strategy to block malaria transmission[57]. Another study demonstrated that OMVs released by Akkermansia muciniphila in the human gut, trained by garlic ELNs (GaELNs), could reverse high-fat diet-induced type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) in mice. This reveals a molecular mechanism where OMVs from gut bacteria trained by plant nanoparticles regulate brain gene expression, influencing the treatment of brain dysfunction caused by metabolic syndrome[58]. Similarly, the highly active A. baumannii phage lysin LysP53 can stimulate OMV production after interacting with A. baumannii, E. coli, and Salmonella. OMVs produced in this manner exhibited higher protein concentrations and lower endotoxin levels, resulting in better therapeutic effects in a mouse model of pneumonia[59].

Nanoparticleization of OMVs is another promising strategy. The most critical factor in inducing an effective immune response is the uptake of antigen particles by APCs[60]. The absorption of bacterial membrane vesicle particles by APCs is size-dependent. Smaller vesicle particles are more efficiently absorbed by APCs, while larger particles can present more antigens. By optimizing the size of bacterial membrane vesicles, the immune response can be maximized[61][62]. Therefore, achieving nanoparticleization of OMVs is a worthwhile supplementary modification strategy.

While genetic engineering, functional molecule loading, and surface functionalization remain the primary methods for modifying OMVs, auxiliary strategies such as fusion culture, cultivation under special environments, and nanoparticleization are essential for enhancing OMV properties. These approaches are essential for advancing OMV-based biomedical applications and overcoming the current limitations in clinical translation.

3. Application of OMVs

OMVs, due to their significant biological relevance and application potential, have garnered widespread attention in recent years, particularly in the fields of anti-infection, oncology, and autoinflammation. OMV research not only provides new therapeutic approaches for these diseases but also offers valuable insights into various physiological and pathological processes, holding promising prospects in the medical field.

3.1 Anti-infective therapy

OMVs have shown considerable promise in combating infections, particularly in inhibiting pathogenic microorganisms. They exert their antimicrobial effects through multiple mechanisms, effectively suppressing the growth and spread of pathogens (Table 1).

OMVs can directly interact with pathogenic microorganisms, disrupting their normal physiological and metabolic processes[63][64]. Inter-microbial competition often occurs via OMVs, which contain specific components capable of binding to surface receptors of pathogens or being internalized by them. This interaction can block nutrient uptake or signal transduction pathways, thereby inhibiting pathogen growth and reproduction[65]. For instance, OMVs enriched with phosphatidylcholine selectively target Plasmodium and deliver effector proteins to kill the parasite, offering a novel strategy for malaria treatment[57]. The OMV protein PA022 from P. aeruginosa inhibits the growth of A. baumannii strains, suggesting that PA022-containing OMVs could serve as a viable alternative for mitigating A. baumannii infections[66]. Furthermore, P. aeruginosa PAO1 produces OMVs carrying a 26-kDa β-glycosidase (autolysin), which exhibits broad-spectrum antibacterial activity, providing a promising avenue for developing new therapeutic strategies[67][68][69]. OMVs derived from E. coli have been utilized as highly selective antimicrobial agents to create stable implant coatings. These OMV coatings exhibit differential therapeutic effects, curing wounds infected with heterologous bacteria while exacerbating those infected with homologous bacteria[70]. However, naturally derived OMVs present significant limitations for anti-infective applications. Specifically, OMVs from certain bacterial species exhibit activity only against closely related bacteria, and the presence of virulence factors and antibiotic resistance genes they carry may potentially exacerbate host infections.

OMVs also exhibit potent immunostimulatory properties, capable of inducing host immune responses[72]. Their surfaces carry various PAMPs, such as LPS, peptidoglycan, and lipoproteins, which are recognized by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs). This recognition activates the innate immune system, promoting the activation of immune cells such as macrophages and DCs, as well as the secretion of cytokines, thereby enhancing the host's ability to combat pathogens. This mechanism underlies the current use of OMVs in anti-infective therapies[73][74][75].

Application of OMVs in anti-infection

| Application strategy | Application principles and examples | Disease model | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct inhibition of pathogenic microorganisms | Virulence factors such as β-lactamase and alkaline phosphatase carried by OMVs inhibit the infection of Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection model | [14], [28] |

| Vaccine adjuvant | OMVs act as vaccine adjuvants, binding antigens to enhance immunogenicity (e.g. binding Neisseria meningitidis antigens for vaccine development) | Neisseria meningitidis vaccine research | [17], [88] |

| Competitive niche | OMVs inhibit the growth of pathogenic microorganisms by occupying their living space (e.g., by suppressing Plasmodium-infected mosquito models) | Mosquito models infected with Plasmodium | [53] |

| Antibacterial activity | OMVs carry antimicrobial proteins (such as hemolytic phospholipase C) that can directly kill pathogens | Acinetobacter baumannii infection model | [12], [67] |

| Modulation of host immunity | OMVs activate macrophages and dendritic cells and enhance immune clearance against H. pylori | Helicobacter pylori infection model | [60], [61] |

| Genetic engineering modification | Knocking out LPS genes in OMVs (such as ΔmsbB mutants) reduces toxicity and preserves immune activation | Mouse infection model | [20], [71] |

Application of OMVs in tumor therapy

| Application strategy | Application principles and examples | Disease model | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immune checkpoint suppression | Genetically engineered OMVs display the PD1 outer domain on the surface, block the PD1/PD-L1 axis, and activate the anti-tumor immune response of T cells | Melanoma model and lung cancer model | [23], [40] |

| Drug delivery | Doxorubicin-loaded OMVs target non-small cell lung cancer, enhancing chemotherapy and inducing an immune response | Non-small cell lung cancer model | [23], [40] |

| Photothermal therapy | OMV Surface Modified Indocyanine Green (ICG) kills tumor cells and releases damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) through photothermal effects | Melanoma model | [38], [86] |

| Gene therapy | OMVs carry siRNA to silence tumor-related genes (such as STAT3) and inhibit tumor growth | Breast cancer model | [37], [86] |

| Combination therapy | OMVs, in combination with oncolytic viruses such as HSV-1, induce panapoptosis to enhance anti-tumor immunity | Colon cancer model | [49] |

| Surface mineralization technology | Melanin-loaded OMV@CaP reduces systemic toxicity through surface mineralization and enhances tumor targeting and photothermal therapy effect | Liver cancer model | [42] |

Several OMV-based strategies have been developed to treat H. pylori infections. OMVs derived from H. pylori cultured under specific conditions or with virulence genes (e.g., CagA, VacA, DupA) deleted exhibit reduced virulence factor content while retaining immunostimulatory capacity, making them effective and safe vaccine candidates[20][21][73]. Similarly, OMVs from Burkholderia pseudomallei grown under macrophage-mimicking conditions have been shown to provide significant protection against pulmonary infections in mice, comparable to live attenuated vaccines. The second-generation M9 OMV vaccine, with its low toxicity, strong adjuvant properties, and immunogenicity, is considered a promising candidate for further development[74]. Furthermore, a case-control study on Neisseria meningitidis serogroup B vaccination found lower incidences of meningitis and gonorrhea in OMV vaccine recipients compared to non-OMV vaccinees, highlighting the potential advantages of OMV-based vaccines in reducing disease incidence[77]. In summary, OMVs function as potent immune activators with considerable promise for vaccine and adjuvant development.

In addition to their immunomodulatory roles, OMVs serve as effective drug delivery vehicles, enabling targeted delivery of antimicrobial agents to infection sites. With the rise of antibiotic resistance due to misuse, OMVs have emerged as a promising biomaterial for antibiotic delivery[78][79][80]. For example, gentamicin-loaded OMVs from P. aeruginosa PAO1 exhibit potent antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus and other pathogens, as they contain both autolysin and small amounts of gentamicin, which act synergistically[81]. Similarly, A. baumannii produces OMVs carrying antibiotics such as amikacin and ciprofloxacin through efflux mechanisms. Mouse studies have shown that OMV-mediated antibiotic delivery not only increases local drug concentrations but also reduces systemic exposure, significantly improving safety and efficacy[67][82]. However, not all antibiotic-loaded OMVs enhance antimicrobial activity. Some may inadvertently promote resistance. For instance, Marie Burt et al. found that OMVs from Klebsiella pneumoniae bound to polymyxin acted as decoys, preventing antibiotic interaction with bacterial surfaces and thereby protecting the bacteria[83]. In summary, OMV-based therapies offer unique advantages for targeted antibiotic delivery due to their exceptional stability and biocompatibility. While OMV-based therapies show substantial promise for anti-infective applications, critical challenges remain that must be resolved before clinical translation.

3.2 Anti-tumor therapy

In recent years, OMVs have shown great promise in anti-tumor therapy, as they can suppress tumor initiation and progression through multiple mechanisms (Table 2).

OMVs can directly act on tumor cells and induce their apoptosis. The enrichment of PAMPs enables OMVs to trigger pyroptosis or apoptosis at the cellular level via receptor-activated death pathways. A recent study found that the OMVs of Fusobacterium nucleatum (Fn-OMV) can upregulate the expression of PANoptosis execution proteins gasdermin D/E (GSDMD/E) and mixed lineage kinase domain-like protein (MLKL) by interfering with the ubiquitination process[53]. Yao Jiang et al. discovered that OMVs derived from E. coli reduce the ratio of the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 to the pro-apoptotic protein Bax, thereby inducing apoptosis in colon cancer cells (CT26) and inhibiting the progression of colon cancer[84]. Consistent with in vitro findings, significant reductions in tumor volume and weight were observed in murine models. However, cells can counteract OMV-induced cell death through multiple pathways, limiting the therapeutic efficacy of OMVs when used alone. For practical applications, modification and engineering of OMVs are required to overcome these limitations.

OMVs can also modify the tumor microenvironment, inhibiting tumor growth, invasion, and metastasis, and enhancing the efficacy of tumor treatments. The tumor microenvironment is a specialized ecosystem created by tumor cells, encompassing immune and inflammatory cells, tumor-associated fibroblasts, adjacent stromal tissues, tumor blood vessels, and various cytokines and chemokines. This environment can facilitate tumor growth, metastasis, and diffusion, while interfering with the efficacy of tumor therapies[85][86]. Engineered OMVs can reprogram the tumor microenvironment, improving anti-tumor effects. For example, engineered OMVs-PD1 can comprehensively regulate the tumor microenvironment. On one hand, OMVs activate the immune response within the host due to their PAMPs, inducing strong expression of IFN-γ and T cell-mediated anti-tumor effects. On the other hand, the programmed death receptor 1 (PD-1) inserted on the surface of OMVs binds to tumor cells, blocking their inhibition of T cell proliferation and promoting tumor cell apoptosis[87]. Shuang Qing et al. covered OMVs with a pH-sensitive CaP shell, which helps macrophages polarize from M2 to M1 and enhances the expression of tumor suppressor genes. Additionally, the outer shell of OMVs can be functionalized with components such as folic acid to promote targeted tumor therapy[88]. In summary, the inherent immunogenicity and novel properties conferred by engineering modifications enable OMVs to reprogram the tumor microenvironment, enhancing their anti-tumor effects.

OMVs can also serve as nanoparticle carriers to precisely deliver anti-tumor active substances to tumor sites. Ze Mi et al. Loaded DOX into Salmonella-derived OMVs to construct OMVs/DOX. By leveraging the ability of Salmonella to selectively colonize hypoxic tumor sites and the selective recognition of OMVs/DOX by neutrophils, they significantly enhanced the therapeutic effect on glioma[89]. OMVs carrying perhexiline also exhibit favorable anti-tumor effects[90]. Oncolytic adenovirus (Ad) infection can promote tumor cell autophagy to exert anti-tumor effects. A study encapsulated Ads in OMVs and covered them with a biomineral shell to promote their accumulation in tumors, thereby achieving enhanced autophagic cascade anti-tumor immunity[91]. Vipul Gujrati et al. engineered E. coli to carry siRNA targeting kinesin spindle protein (KSP) with an affinity for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), successfully inhibiting the growth of breast cancer cells[92]. The nanoscale dimensions of OMVs confer potent tissue penetration capabilities, facilitating their use as effective drug delivery vehicles for targeted anti-tumor therapy.

Furthermore, OMVs are frequently employed as delivery vehicles for tumor antigens and as adjuvants to enhance tumor therapeutic outcomes. Due to the marked interpatient heterogeneity of tumor cells, conventional vaccine formulations exhibit limited efficacy across diverse cases, highlighting the need for personalized vaccine strategies. To address this, bacterial OMV-based nanoplatforms have emerged as customizable delivery systems capable of incorporating patient-specific tumor antigen profiles. These OMV platforms exhibit dual functionality as both antigen carriers and built-in immunostimulants, facilitating the clinical development of personalized cancer vaccines[93]. Epitopes derived from embryonic stem cells (ESCs) can serve as therapeutic tumor vaccines against various types of tumors. Meiling Jin et al. utilized OMVs to deliver ESC-derived tumor antigens and immune checkpoint inhibitors (PD-L1 antibodies), effectively inhibiting tumor growth[94]. Additionally, a study developed an oral tumor vaccine based on OMVs. Yale Yue et al. genetically engineered E. coli to produce OMVs carrying tumor antigens in situ within the intestine. These OMVs then traversed the intestinal epithelial barrier and were recognized by immune cells in the lamina propria, effectively activating tumor antigen-specific immune responses and significantly suppressing tumor growth[95]. OMVs can also be employed for therapeutic mRNA vaccination. Yao Li et al. added RNA-binding protein L7Ae and lysosomal escape protein listeriolysin O to the surface of OMVs (OMV-LL). OMV-LL bound to mRNA antigens through L7Ae and delivered them to DCs, achieving cross-presentation through listeriolysin O-mediated endosomal escape, which significantly inhibited melanoma progression[96]. In summary, OMVs—acting as nanocarriers with intrinsic immune adjuvant properties—are widely utilized in tumor vaccine research to deliver tumor antigens and elicit robust antigen-specific anti-tumor immune responses.

3.3 Autoimmune and inflammatory diseases

The inflammatory response is a complex physiological process triggered by injury and infection, but excessive or prolonged inflammation can contribute to the onset and progression of autoinflammatory diseases. Autoimmune diseases occur when the body's immune system mistakenly attacks its own healthy tissue cells. Due to the diverse and complex mechanisms underlying their development, autoimmune diseases encompass a wide range of conditions that can involve multiple systems and organs, leading to significant health issues. OMVs can modulate autoimmune and inflammatory diseases through various mechanisms (Table 3).

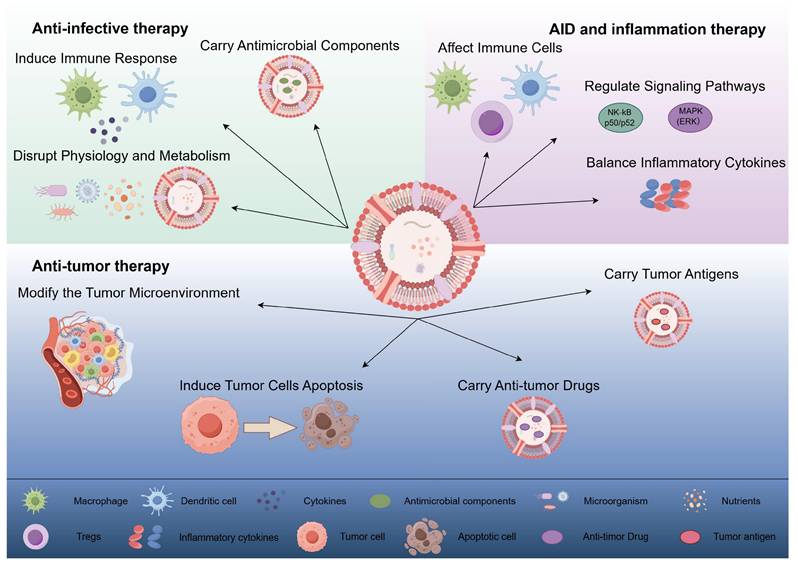

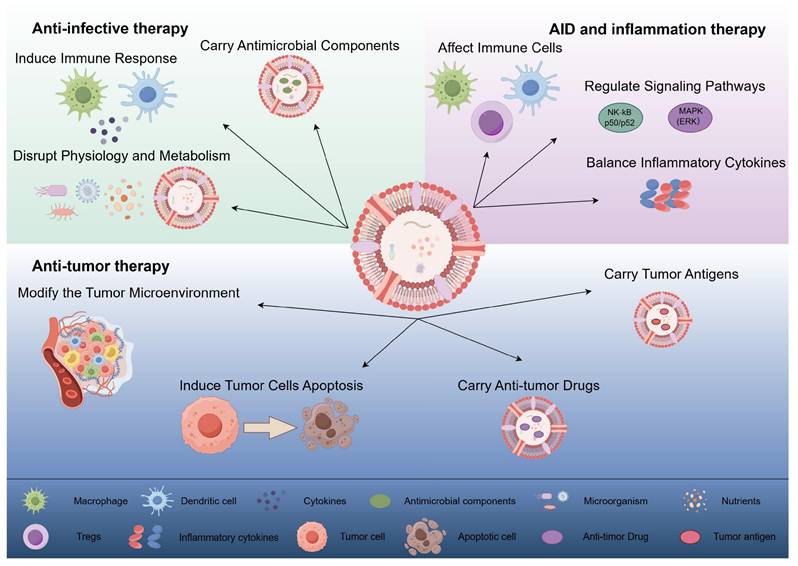

OMVs exert anti-infective, anti-tumor, and autoimmune/inflammatory effects through different mechanisms. (1) Anti-infective therapy: OMVs interfere with the normal physiological and metabolic processes of microorganisms by directly acting on them, inducing host immune responses, and carrying antimicrobial components to exert anti-infective effects. (2) Anti-tumor therapy: OMVs can directly induce apoptosis in tumor cells, modify the tumor microenvironment, and deliver anti-tumor drugs and tumor antigens to exert anti-tumor effects. (3) Autoimmune disease and inflammation therapy: OMVs contribute to the therapy of autoimmune diseases and inflammation by affecting immune cell activation and function, regulating inflammation-related signaling pathways, and promoting the balance of anti-inflammatory and pro-inflammatory cytokines. (By Figdraw).

Application of OMVs in autoimmune and inflammatory diseases

| Application strategy | Application principles and examples | Disease model | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adjust inflammatory signaling pathways | OMVs reduce inflammation by inhibiting NF-κB and MAPK pathways (as in rheumatoid arthritis models) | Rheumatoid arthritis models | [20], [63] |

| Induce immune tolerance | OMVs carry autoantigens (such as SLE-associated antigens) that induce immune tolerance through oral tolerance strategies | Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) model | [62], [102] |

| Intestinal flora adjustment | Garlic exosome (GaELNs)-trained Akkermansia muciniphila releases OMVs and reverses high-fat diet-induced type 2 diabetes | Mouse model of type 2 diabetes mellitus | [54] |

| Neuroinflammatory regulation | Helicobacter pylori OMVs promote Alzheimer's disease neuroinflammation through the complement C3-C3aR signaling pathway | Alzheimer's disease model | [105] |

| Anti-inflammatory cytokine induction | OMVs promote the secretion of anti-inflammatory factors IL-10 and TGF-β and inhibit pro-inflammatory factors (such as TNF-α) | Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) model | [96], [98] |

| Skin inflammation inhibition | Parabacteroides goldsteinii-derived OMVs reduce psoriasis inflammation by regulating skin flora | Psoriasis mouse model | [102] |

In inflammatory diseases, OMVs primarily function through three mechanisms. First, OMVs regulate cell proliferation, differentiation, and cytokine secretion by interacting with receptors on the surface of immune cells[99]. For example, Durant et al. found that during in vitro culture of DCs, Polysaccharide A expressed on the surface of Bacteroides tenuis OMVs promoted the production of regulatory T cell (Tregs) responses and interleukin-10 by DCs in a TLR-2 and GADD45α-dependent manner, showing beneficial effects in a mouse model of acute colitis[99]. Additionally, Chu et al. conducted a study using Atg16l1fl/fl Cd11cCre mice, demonstrating that B. tenuis OMVs can activate LC3-related phagocytosis (LAP) via the ATG16L1 gene, acting on TLRs and inducing Tregs to inhibit mucosal inflammation, thereby offering protection in colitis[101].

Additionally, OMVs have a regulatory effect on cell signaling pathways, influencing the cellular response to various environmental and situational factors. They can interfere with intracellular signaling pathways, such as the NF-κB and MAPK pathways[76]. For instance, Zhang et al. demonstrated that Fn-OMVs enter human periodontal ligament stem cells (hPDLSCs) primarily through fosprotein-dependent endocytosis, activating NF-κB signaling and impairing osteogenic differentiation. Furthermore, in a periodontitis mouse model, OMVs were found to facilitate signal transduction via the NF-κB pathway, leading to the activation of inflammasomes and the release of IL-1β and IL-18[97].

OMVs predominantly function by regulating inflammatory factors and can effectively activate inflammasome pathways, particularly those mediated by NLRP3 and Caspase-11/4. For example, Chen et al. investigated streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats and found that fecal bacterial OMVs (fBEVs) significantly upregulated the expression of pro-caspase-11, active caspase-11, pro-caspase-1, and active caspase-1 in renal tissue. Similarly, in HK-2 cells, fBEVs activated caspase-4 (a human homolog of caspase-11), and silencing caspase-4 with siRNA inhibited this process[96]. Zhang et al. established a rat model of periodontitis and found that Fn-OMVs triggered the activation of NLRP3 inflammasomes in hPDLSCs and the subsequent release of IL-1β and IL-18, resulting in impaired mineralization in these cells[97]. Moreover, compared to wild-type (WT) cells, OMV stimulation increased the transcription of multiple pro-inflammatory cytokines in Atg16L1ΔCD11c DCs, which are key complexes involved in the inflammatory response[101][107].

For autoimmune diseases, OMVs function through a similar mechanism. They may promote the production and function of Tregs, thereby leading to autoimmune responses[100][102]. This principle can be applied to regulate the quantity and expression of immune cells, suppressing excessive immune responses. OMVs may also stimulate the immune system through signaling pathways, triggering corresponding responses. For instance, OMVs can regulate toll-like receptor-mediated signaling pathways to inhibit the inflammatory response in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)[76]. Additionally, OMVs may influence the autoimmune process by affecting the activation and regulation of cytokines. Chen et al. conducted a comprehensive study and found that OMVs can regulate immune cells and cytokines in various ways, a response confirmed in multiple autoimmune disease models, including lupus erythematosus, multiple sclerosis, and rheumatoid arthritis[106].

OMVs also target autoimmune and inflammatory diseases through various mechanisms, such as reducing autoimmune responses, promoting immune tolerance, and enhancing the self-repair ability of the immune system. This may occur through simulating pathogen infection or providing specific immune stimulation signals. OMVs can promote immune system tolerance to self-antigens[58][104]. In the study of myasthenia gravis, patients were induced to develop immune tolerance through oral tolerance treatment strategies, leading to a reduction in disease symptoms[104]. By training the immune system, OMVs may enhance its ability to repair itself, improving its capacity to respond to autoimmune disease challenges. This enhancement may involve aspects such as the proliferation, differentiation, and functional improvement of immune cells[99].

OMVs, based on these mechanisms, have broad therapeutic applications. They can serve as diagnostic biomarkers; for instance, elevated levels of OMVs derived from the gut microbiota are associated with the severity of diabetic nephropathy[96]. Similarly, OMV-related proteins in periodontitis can indicate disease activity[97]. Given their immune characteristics, OMVs can also be developed as a vaccine platform for treating inflammatory diseases or symptoms. In 2015, the success of the Neisseria meningitidis OMV-based vaccine laid the foundation for developing similar strategies against other pathogens[98]. Additionally, OMVs naturally possess the ability to cross biological barriers and target specific cells, making them attractive drug delivery carriers. Engineered OMVs are currently used to deliver therapeutic agents to inflammatory sites while minimizing systemic side effects[102]. Furthermore, regulating the microbiome, particularly targeting the gut microbiota, may offer new approaches to treating related diseases. Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) shows promise in restoring normal OMV profiles and reducing inflammation in diabetic models[96].

Despite the great potential of OMVs in treating inflammatory and autoimmune diseases, several challenges remain. Although OMVs activate the immune system through various mechanisms, the inflammatory responses they trigger can negatively impact treatment. OMVs from H. pylori induce local and systemic inflammatory responses by releasing pro-inflammatory factors like LPS, which may result in serious consequences, such as gastric mucosal barrier dysfunction and gastric cancer[105]. Moreover, OMVs can exacerbate disease pathology by activating autoimmunity. For example, H. pylori OMVs may trigger an autoimmune response through components similar to host blood group antigens[105][107]. Recent studies have also shown that H. pylori OMVs are absorbed by brain astrocytes, exacerbating amyloid-β accumulation and cognitive decline through the complement component 3 (C3)-C3a receptor (C3aR) signaling pathway, accelerating the development of Alzheimer's disease[108][109]. Additionally, the toxicity of OMVs and the limitations of immature production and purification technologies remain major barriers to their application.

4. Conclusion

The application of OMVs in anti-infection, tumor therapy, and autoinflammation is highly significant. While progress has been made through exploration in various fields, many issues still need to be further studied and resolved.

4.1 Current Status

As a novel biomaterial, OMVs have made significant progress in bioengineering. Gene editing, functional molecular loading, and surface functionalization for OMVs have largely been realized, but further research efforts are still required to bridge the gap from basic to clinical applications. In the realm of anti-infection, OMVs have shown promise in inhibiting pathogenic microorganisms and serving as vaccine adjuvants, offering new approaches for the prevention and treatment of infectious diseases. However, the mechanisms of action need further clarification to optimize their application and minimize potential risks. In cancer therapy, OMVs' effects on tumor cells and their role in tumor immunotherapy indicate their potential in cancer treatment. However, to achieve broader and more effective clinical applications, the heterogeneity of tumors must be addressed. In autoinflammatory diseases, OMVs' regulatory effects on the inflammatory response and their therapeutic potential provide new hope for treatment. However, more in-depth research is needed to clarify their specific targets and regulatory networks.

4.2 Future Perspectives

Despite notable advances in OMV engineering and therapeutic applications, several critical challenges must be addressed before clinical translation is feasible. First, the lack of standardized and scalable manufacturing workflows remains a major obstacle. Current OMV production relies heavily on strain-specific optimization and laboratory-scale isolation procedures, leading to batch-to-batch variability and limited reproducibility. Future efforts should focus on developing GMP-compliant large-scale fermentation, purification, and endotoxin removal processes, along with universally accepted quality control benchmarks.

Second, the safety assessment of OMVs remains insufficient. Endotoxin contamination, unintended immune hyperactivation, and incomplete characterization of OMV cargo continue to pose risks. Comprehensive toxicology, immunogenicity, and biodistribution studies in patient-derived xenograft (PDX) or humanized models are essential to support clinical translation. In parallel, synthetic biology strategies, such as LPS detoxification, lipid A remodeling, and surface deactivation, may enhance safety while preserving adjuvant efficacy.

Third, improvements in targeting efficiency and functional precision are still needed. Although surface engineering and genetic modification have enhanced selectivity, targeting performance remains heterogeneous across tumor types, inflammatory states, and infectious microenvironments. Future approaches should explore modular plug-and-play antigen-display systems, programmable targeting ligands, and microenvironment-responsive OMV designs to achieve more precise therapeutic outcomes.

Finally, integrating OMV-based platforms with other therapeutic modalities—including immune checkpoint inhibitors, oncolytic viruses, mRNA vaccines, and nanomedicines—represents a promising yet underexplored direction. Advancements in this area will require sustained interdisciplinary collaboration across microbiology, immunology, materials science, and clinical medicine to develop highly personalized and clinically deployable OMV-based therapies.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Beijing Natural Science Foundation [F252052]; the Peking University Third Hospital Fund for Interdisciplinary Research [BYSYJC2023005, BYSYJC2024020]; and the State Key Laboratory of Vascular Homeostasis and Remodeling Open Research Fund [2025-VHR-O-SY-21].

We thank Bullet Edits Limited for the linguistic editing and proofreading of the manuscript.

Author contributions

JZ designed the research. YW, YS, and XJ reviewed and analyzed the papers and wrote the manuscript. ZH, ZW, and ZZ revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the final version.

Competing interests

The authors have declared that no competing interest exists.

References

1. Schwechheimer C, Kulp A, Kuehn MJ. Modulation of bacterial outer membrane vesicle production by envelope structure and content. BMC Microbiol. 2014Dec21;14:324 doi: 10.1186/s12866-014-0324-1. PMID: 25528573; PMCID: PMC4302634

2. Paulsson M, Kragh KN, Su YC, Sandblad L, Singh B, Bjarnsholt T, Riesbeck K. Peptidoglycan-Binding Anchor Is a Pseudomonas aeruginosa OmpA Family Lipoprotein With Importance for Outer Membrane Vesicles, Biofilms, and the Periplasmic Shape. Front Microbiol. 2021Feb25;12:639582 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.639582. PMID: 33717034; PMCID: PMC7947798

3. Turner L, Praszkier J, Hutton ML, Steer D, Ramm G, Kaparakis-Liaskos M, Ferrero RL. Increased Outer Membrane Vesicle Formation in a Helicobacter pylori tolB Mutant. Helicobacter. 2015Aug;20(4):269-83 doi: 10.1111/hel.12196. Epub 2015 Feb 9. PMID: 25669590

4. McBroom AJ, Kuehn MJ. Release of outer membrane vesicles by Gram-negative bacteria is a novel envelope stress response. Mol Microbiol. 2007Jan;63(2):545-58 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05522.x. Epub 2006 Dec 5. PMID: 17163978; PMCID: PMC1868505

5. Schertzer JW, Whiteley M. A bilayer-couple model of bacterial outer membrane vesicle biogenesis. mBio. 2012Mar13;3(2):e00297-11 doi: 10.1128/mBio.00297-11. PMID: 22415005; PMCID: PMC3312216

6. Turnbull L, Toyofuku M, Hynen AL, Kurosawa M, Pessi G, Petty NK, Osvath SR, Cárcamo-Oyarce G, Gloag ES, Shimoni R, Omasits U, Ito S, Yap X, Monahan LG, Cavaliere R, Ahrens CH, Charles IG, Nomura N, Eberl L, Whitchurch CB. Explosive cell lysis as a mechanism for the biogenesis of bacterial membrane vesicles and biofilms. Nat Commun. 2016Apr14;7:11220 doi: 10.1038/ncomms11220. PMID: 27075392; PMCID: PMC4834629

7. Lee J, Kim OY, Gho YS. Proteomic profiling of Gram-negative bacterial outer membrane vesicles: Current perspectives. Proteomics Clin Appl. 2016Oct;10(9-10):897-909 doi: 10.1002/prca.201600032. Epub 2016 Sep 22. PMID: 27480505

8. Zavan L, Fang H, Johnston EL, Whitchurch C, Greening DW, Hill AF, Kaparakis-Liaskos M. The mechanism of Pseudomonas aeruginosa outer membrane vesicle biogenesis determines their protein composition. Proteomics. 2023May;23(10):e2200464 doi: 10.1002/pmic.202200464. Epub 2023 Mar 17. PMID: 36781972

9. Johnston EL, Guy-Von Stieglitz S, Zavan L, Cross J, Greening DW, Hill AF, Kaparakis-Liaskos M. The effect of altered pH growth conditions on the production, composition, and proteomes of Helicobacter pylori outer membrane vesicles. Proteomics. 2024Jun;24(11):e2300269 doi: 10.1002/pmic.202300269. Epub 2023 Nov 22. PMID: 37991474

10. Avila-Calderón ED, Ruiz-Palma MDS, Aguilera-Arreola MG, Velázquez-Guadarrama N, Ruiz EA, Gomez-Lunar Z, Witonsky S, Contreras-Rodríguez A. Outer Membrane Vesicles of Gram-Negative Bacteria: An Outlook on Biogenesis. Front Microbiol. 2021Mar4;12:557902 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.557902. PMID: 33746909; PMCID: PMC7969528

11. Elhenawy W, Debelyy MO, Feldman MF. Preferential packing of acidic glycosidases and proteases into Bacteroides outer membrane vesicles. mBio. 2014Mar11;5(2):e00909-14 doi: 10.1128/mBio.00909-14. PMID: 24618254; PMCID: PMC3952158

12. Dhurve G, Madikonda AK, Jagannadham MV, Siddavattam D. Outer Membrane Vesicles of Acinetobacter baumannii DS002 Are Selectively Enriched with TonB-Dependent Transporters and Play a Key Role in Iron Acquisition. Microbiol Spectr. 2022Apr27;10(2):e0029322 doi: 10.1128/spectrum.00293-22. Epub 2022 Mar 10. PMID: 35266817; PMCID: PMC9045253

13. Zhao Z, Wang L, Miao J, Zhang Z, Ruan J, Xu L, Guo H, Zhang M, Qiao W. Regulation of the formation and structure of biofilms by quorum sensing signal molecules packaged in outer membrane vesicles. Sci Total Environ. 2022Feb1;806(Pt 4):151403 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.151403. Epub 2021 Nov 4. PMID: 34742801

14. Bomberger JM, Maceachran DP, Coutermarsh BA, Ye S, O'Toole GA, Stanton BA. Long-distance delivery of bacterial virulence factors by Pseudomonas aeruginosa outer membrane vesicles. PLoS Pathog. 2009Apr;5(4):e1000382 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000382. Epub 2009 Apr 10. PMID: 19360133; PMCID: PMC2661024

15. Schulz E, Goes A, Garcia R, Panter F, Koch M, Müller R, Fuhrmann K, Fuhrmann G. Biocompatible bacteria-derived vesicles show inherent antimicrobial activity. J Control Release. 2018 Nov 28;290:46-55. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2018.09.030. Epub 2018 Oct 5. Erratum in: J Control Release. 2019Jan10;293:155-157 doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2018.11.027. PMID: 30292423

16. Sheng K, Feng Y, Li L, Kong F, Gao J, Kong X. Engineered bacterial outer membrane vesicles: a versatile bacteria-based weapon against gastrointestinal tumors. Theranostics. 2024Jan1;14(2):761-787 doi: 10.7150/thno.85917. PMID: 38169585; PMCID: PMC10758051

17. Mancini F, Rossi O, Necchi F, Micoli F. OMV Vaccines and the Role of TLR Agonists in Immune Response. Int J Mol Sci. 2020Jun21;21(12):4416 doi: 10.3390/ijms21124416. PMID: 32575921; PMCID: PMC7352230

18. Luo Z, Cheng X, Feng B, Fan D, Liu X, Xie R, Luo T, Wegner SV, Ma D, Chen F, Zeng W. Engineering Versatile Bacteria-Derived Outer Membrane Vesicles: An Adaptable Platform for Advancing Cancer Immunotherapy. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2024Sep;11(33):e2400049 doi: 10.1002/advs.202400049. Epub 2024 Jul 1. PMID: 38952055; PMCID: PMC11434149

19. Xie J, Li Q, Haesebrouck F, Van Hoecke L, Vandenbroucke RE. The tremendous biomedical potential of bacterial extracellular vesicles. Trends Biotechnol. 2022Oct;40(10):1173-1194 doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2022.03.005. Epub 2022 May 14. PMID: 35581020

20. Ye H, Wang H, Han B, Chen K, Wang X, Ma F, Cheng L, Zheng S, Zhao X, Zhu J, Li J, Hong M. Guizhi Shaoyao Zhimu decoction inhibits neutrophil extracellular traps formation to relieve rheumatoid arthritis via gut microbial outer membrane vesicles. Phytomedicine. 2024Nov15;136:156254 doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2024.156254. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 39586125

21. Shi R, Lv R, Dong Z, Cao Q, Wu R, Liu S, Ren Y, Liu Z, van der Mei HC, Liu J, Busscher HJ. Magnetically-targetable outer-membrane vesicles for sonodynamic eradication of antibiotic-tolerant bacteria in bacterial meningitis. Biomaterials. 2023Nov;302:122320 doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2023.122320. Epub 2023 Sep 17. PMID: 37738742

22. Fang Y, Yang G, Wu X, Lin C, Qin B, Zhuang L. A genetic engineering strategy to enhance outer membrane vesicle-mediated extracellular electron transfer of Geobacter sulfurreducens. Biosens Bioelectron. 2024Apr15;250:116068 doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2024.116068. Epub 2024 Jan 23. PMID: 38280298

23. Li Y, Zhao R, Cheng K, Zhang K, Wang Y, Zhang Y, Li Y, Liu G, Xu J, Xu J, Anderson GJ, Shi J, Ren L, Zhao X, Nie G. Bacterial Outer Membrane Vesicles Presenting Programmed Death 1 for Improved Cancer Immunotherapy via Immune Activation and Checkpoint Inhibition. ACS Nano. 2020Dec22;14(12):16698-16711 doi: 10.1021/acsnano.0c03776. Epub 2020 Nov 24. PMID: 33232124

24. Kuerban K, Gao X, Zhang H, Liu J, Dong M, Wu L, Ye R, Feng M, Ye L. Doxorubicin-loaded bacterial outer-membrane vesicles exert enhanced anti-tumor efficacy in non-small-cell lung cancer. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2020Aug;10(8):1534-1548 doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2020.02.002. Epub 2020 Feb 20. PMID: 32963948; PMCID: PMC7488491

25. Yu Y, Feng L, Liu Z. Nanomedicine sheds new light on cancer immunotherapy. Med Rev (2021). 2023Apr17;3(2):188-192 doi: 10.1515/mr-2023-0005. PMID: 37724084; PMCID: PMC10471084

26. Gao J, Dong X, Wang Z. Generation, purification and engineering of extracellular vesicles and their biomedical applications. Methods. 2020May1;177:114-125 doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2019.11.012. Epub 2019 Nov 30. PMID: 31790730; PMCID: PMC7198327

27. Li DF, Yang MF, Xu J, Xu HM, Zhu MZ, Liang YJ, Zhang Y, Tian CM, Nie YQ, Shi RY, Wang LS, Yao J. Extracellular Vesicles: The Next Generation Theranostic Nanomedicine for Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Int J Nanomedicine. 2022Sep5;17:3893-3911 doi: 10.2147/IJN.S370784. PMID: 36092245; PMCID: PMC9462519

28. Gao J, Su Y, Wang Z. Engineering bacterial membrane nanovesicles for improved therapies in infectious diseases and cancer. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2022Jul;186:114340 doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2022.114340. Epub 2022 May 13. PMID: 35569561; PMCID: PMC9899072

29. Orench-Rivera N, Kuehn MJ. Environmentally controlled bacterial vesicle-mediated export. Cell Microbiol. 2016Nov;18(11):1525-1536 doi:10.1111/cmi.12676

30. Fan S, Han H, Yan Z, Lu Y, He B, Zhang Q. Lipid-based nanoparticles for cancer immunotherapy. Med Rev (Berl). 2023Aug17;3(3):230-269 doi: 10.1515/mr-2023-0020. PMID: 37789955; PMCID: PMC10542882

31. Zhao Z, Wang D, Li Y. Versatile biomimetic nanomedicine for treating cancer and inflammation disease. Med Rev (Berl). 2023Apr7;3(2):123-151 doi: 10.1515/mr-2022-0046. PMID: 37724085; PMCID: PMC10471090

32. Liu X, Zhang X, Li J, Meng H. Enrichment of nano delivery platforms for mRNA-based nanotherapeutics. Med Rev (2021). 2023Sep20;3(4):356-361 doi: 10.1515/mr-2023-0010. PMID: 38235403; PMCID: PMC10790206

33. Heggie A, Thurston TLM, Ellis T. Microbial messengers: nucleic acid delivery by bacteria. Trends Biotechnol. 2025Jan;43(1):145-161 doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2024.07.010. Epub 2024 Aug 7. PMID: 39117490

34. Lin IY, Van TT, Smooker PM. Live-Attenuated Bacterial Vectors: Tools for Vaccine and Therapeutic Agent Delivery. Vaccines (Basel). 2015Nov10;3(4):940-72 doi: 10.3390/vaccines3040940. PMID: 26569321; PMCID: PMC4693226

35. Schoen C, Kolb-Mäurer A, Geginat G, Löffler D, Bergmann B, Stritzker J, Szalay AA, Pilgrim S, Goebel W. Bacterial delivery of functional messenger RNA to mammalian cells. Cell Microbiol. 2005May;7(5):709-24 doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00507.x. PMID: 15839900

36. Cong Z, Li Y, Xie L, Chen Q, Tang M, Thongpon P, Jiao Y, Wu S. Engineered Microrobots for Targeted Delivery of Bacterial Outer Membrane Vesicles (OMV) in Thrombus Therapy. Small. 2024Oct;20(40):e2400847 doi: 10.1002/smll.202400847. Epub 2024 May 27. PMID: 38801399

37. Tang S, Tang D, Zhou H, Li Y, Zhou D, Peng X, Ren C, Su Y, Zhang S, Zheng H, Wan F, Yoo J, Han H, Ma X, Gao W, Wu S. Bacterial outer membrane vesicle nanorobot. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2024Jul23;121(30):e2403460121 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2403460121. Epub 2024 Jul 15. PMID: 39008666; PMCID: PMC11287275

38. Peng LH, Wang MZ, Chu Y, Zhang L, Niu J, Shao HT, Yuan TJ, Jiang ZH, Gao JQ, Ning XH. Engineering bacterial outer membrane vesicles as transdermal nanoplatforms for photo-TRAIL-programmed therapy against melanoma. Sci Adv. 2020Jul3;6(27):eaba2735 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aba2735. PMID: 32923586; PMCID: PMC7455490

39. Won S, Lee C, Bae S, Lee J, Choi D, Kim MG, Song S, Lee J, Kim E, Shin H, Basukala A, Lee TR, Lee DS, Gho YS. Mass-produced gram-negative bacterial outer membrane vesicles activate cancer antigen-specific stem-like CD8+ T cells which enables an effective combination immunotherapy with anti-PD-1. J Extracell Vesicles. 2023Aug;12(8):e12357 doi: 10.1002/jev2.12357. PMID: 37563797; PMCID: PMC10415594

40. Caruana JC, Walper SA. Bacterial membrane vesicles as mediators of microbe-microbe and microbe-host community interactions. Front Microbiol. 2020Apr28;11:432 doi:10.3389/fmicb.2020.00432

41. Cheng K, Zhao R, Li Y, Qi Y, Wang Y, Zhang Y, Qin H, Qin Y, Chen L, Li C, Liang J, Li Y, Xu J, Han X, Anderson GJ, Shi J, Ren L, Zhao X, Nie G. Bioengineered bacteria-derived outer membrane vesicles as a versatile antigen display platform for tumor vaccination via Plug-and-Display technology. Nat Commun. 2021Apr6;12(1):2041 doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-22308-8. PMID: 33824314; PMCID: PMC8024398

42. Qin H, Li H, Zhu J, Qin Y, Li N, Shi J, Nie G, Zhao R. Biogenetic Vesicle-Based Cancer Vaccines with Tunable Surface Potential and Immune Potency. Small. 2023Oct;19(42):e2303225 doi: 10.1002/smll.202303225. Epub 2023 Jun 17. PMID: 37330651

43. Weyant KB, Oloyede A, Pal S, Liao J, Jesus MR, Jaroentomeechai T, Moeller TD, Hoang-Phou S, Gilmore SF, Singh R, Pan DC, Putnam D, Locher C, de la Maza LM, Coleman MA, DeLisa MP. A modular vaccine platform enabled by decoration of bacterial outer membrane vesicles with biotinylated antigens. Nat Commun. 2023Jan28;14(1):464 doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-36101-2. PMID: 36709333; PMCID: PMC9883832

44. Chen X, Li P, Luo B, Song C, Wu M, Yao Y, Wang D, Li X, Hu B, He S, Zhao Y, Wang C, Yang X, Hu J. Surface Mineralization of Engineered Bacterial Outer Membrane Vesicles to Enhance Tumor Photothermal/Immunotherapy. ACS Nano. 2024Jan16;18(2):1357-1370 doi: 10.1021/acsnano.3c05714. Epub 2024 Jan 2. PMID: 38164903

45. Sun Y, Ma YY, Shangguan S, Ruan Y, Bai T, Xue P, Zhuang H, Cao W, Cai H, Tang E, Wu Z, Yang M, Zeng Y, Sun J, Fan Y, Zeng X, Yan S. Metal ions-anchored bacterial outer membrane vesicles for enhanced ferroptosis induction and immune stimulation in targeted antitumor therapy. J Nanobiotechnology. 2024Aug9;22(1):474 doi: 10.1186/s12951-024-02747-3. PMID: 39123234; PMCID: PMC11311927

46. Ding H, Zhang Y, Mao Y, Li Y, Shen Y, Sheng J, Gu N. Modulation of macrophage polarization by iron-based nanoparticles. Med Rev (2021). 2023Apr18;3(2):105-122 doi: 10.1515/mr-2023-0002. PMID: 37724082; PMCID: PMC10471121

47. Zhao X, Zhao R, Nie G. Nanocarriers based on bacterial membrane materials for cancer vaccine delivery. Nat Protoc. 2022Oct;17(10):2240-2274 doi: 10.1038/s41596-022-00713-7. Epub 2022 Jul 25. PMID: 35879454

48. Yue Y, Xu J, Li Y, Cheng K, Feng Q, Ma X, Ma N, Zhang T, Wang X, Zhao X, Nie G. Antigen-bearing outer membrane vesicles as tumour vaccines produced in situ by ingested genetically engineered bacteria. Nat Biomed Eng. 2022Jul;6(7):898-909 doi: 10.1038/s41551-022-00886-2. Epub 2022 May 2. PMID: 35501399

49. Chen Q, Huang G, Wu W, Wang J, Hu J, Mao J, Chu PK, Bai H, Tang G. A Hybrid Eukaryotic-Prokaryotic Nanoplatform with Photothermal Modality for Enhanced Antitumor Vaccination. Adv Mater. 2020Apr;32(16):e1908185 doi: 10.1002/adma.201908185. Epub 2020 Feb 28. PMID: 32108390

50. Huang Y, Wang C, Chen Y, Wang D, Yao D. Nanomedicine-induced pyroptosis for anti-tumor immunotherapy: Mechanism analysis and application prospects. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2025Jul;15(7):3487-3510 doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2025.05.021. Epub 2025 May 26. PMID: 40698137; PMCID: PMC12278415

51. Yao D, Wang Y, Dong X. et al. Renal-clearable and tumor-retained nanodots overcoming metabolic reprogramming to boost mitochondrial-targeted photodynamic therapy in triple-negative breast cancer. J Nanobiotechnol. 2025;23:195 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12951-025-03264-7

52. Chen Y. et al. Shining a light on pyroptosis in cancer chemotherapy by multi-modal imaging with a dual-channel nanoreporter. Chemical Engineering Journal. 2025;513:1385-8947 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2025.163018

53. Wang S, Song A, Xie J, Wang YY, Wang WD, Zhang MJ, Wu ZZ, Yang QC, Li H, Zhang J, Sun ZJ. Fn-OMV potentiates ZBP1-mediated PANoptosis triggered by oncolytic HSV-1 to fuel antitumor immunity. Nat Commun. 2024Apr30;15(1):3669 doi: 10.1038/s41467-024-48032-7. PMID: 38693119; PMCID: PMC11063137

54. Ban W, Sun M, Huang H, Huang W, Pan S, Liu P, Li B, Cheng Z, He Z, Liu F, Sun J. Engineered bacterial outer membrane vesicles encapsulating oncolytic adenoviruses enhance the efficacy of cancer virotherapy by augmenting tumor cell autophagy. Nat Commun. 2023May22;14(1):2933 doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-38679-z. PMID: 37217527; PMCID: PMC10203215

55. Loewe D, Dieken H, Grein TA, Weidner T, Salzig D, Czermak P. Opportunities to debottleneck the downstream processing of the oncolytic measles virus. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2020Mar;40(2):247-264 doi: 10.1080/07388551.2019.1709794. Epub 2020 Jan 9. PMID: 31918573

56. Peng X, Luo Y, Yang L, Yang YY, Yuan P, Chen X, Tian GB, Ding X. A multiantigenic antibacterial nanovaccine utilizing hybrid membrane vesicles for combating Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. J Extracell Vesicles. 2024Oct;13(10):e12524 doi: 10.1002/jev2.12524. PMID: 39400457; PMCID: PMC11472236

57. Gao H, Jiang Y, Wang L, Wang G, Hu W, Dong L, Wang S. Outer membrane vesicles from a mosquito commensal mediate targeted killing of Plasmodium parasites via the phosphatidylcholine scavenging pathway. Nat Commun. 2023Aug24;14(1):5157 doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-40887-6. PMID: 37620328; PMCID: PMC10449815

58. Sundaram K, Teng Y, Mu J, Xu Q, Xu F, Sriwastva MK, Zhang L, Park JW, Zhang X, Yan J, Zhang SQ, Merchant ML, Chen SY, McClain CJ, Dryden GW, Zhang HG. Outer Membrane Vesicles Released from Garlic Exosome-like Nanoparticles (GaELNs) Train Gut Bacteria that Reverses Type 2 Diabetes via the Gut-Brain Axis. Small. 2024May;20(20):e2308680 doi: 10.1002/smll.202308680. Epub 2024 Jan 15. PMID: 38225709; PMCID: PMC11102339

59. Li C, Xue H, Du X, Nyaruaba R, Yang H, Wei H. Outer membrane vesicles generated by an exogenous bacteriophage lysin and protection against Acinetobacter baumannii infection. J Nanobiotechnology. 2024May21;22(1):273 doi: 10.1186/s12951-024-02553-x. PMID: 38773507; PMCID: PMC11110425

60. Qiao L, Rao Y, Zhu K, Rao X, Zhou R. Engineered Remolding and Application of Bacterial Membrane Vesicles. Front Microbiol. 2021Oct8;12:729369 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.729369. PMID: 34690971; PMCID: PMC8532528

61. Gnopo YMD, Misra A, Hsu HL, DeLisa MP, Daniel S, Putnam D. Induced fusion and aggregation of bacterial outer membrane vesicles: Experimental and theoretical analysis. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2020Oct15;578:522-532 doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2020.04.068. Epub 2020 Apr 20. PMID: 32540551; PMCID: PMC7487024

62. Wu G, Ji H, Guo X, Li Y, Ren T, Dong H, Liu J, Liu Y, Shi X, He B. Nanoparticle reinforced bacterial outer-membrane vesicles effectively prevent fatal infection of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae. Nanomedicine. 2020Feb;24:102148 doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2019.102148. Epub 2019 Dec 27. PMID: 31887427

63. Mosby CA, Bhar S, Phillips MB, Edelmann MJ, Jones MK. Interaction with mammalian enteric viruses alters outer membrane vesicle production and content by commensal bacteria. J Extracell Vesicles. 2022Jan;11(1):e12172 doi: 10.1002/jev2.12172. PMID: 34981901; PMCID: PMC8725172

64. Ghosh S, Mohamed Z, Shin JH, Bint E Naser SF, Bali K, Dörr T, Owens RM, Salleo A, Daniel S. Impedance sensing of antibiotic interactions with a pathogenic E. coli outer membrane supported bilayer. Biosens Bioelectron. 2022May15;204:114045 doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2022.114045. Epub 2022 Jan 29. PMID: 35180690; PMCID: PMC9526520

65. Li C, Zhu L, Wang D, Wei Z, Hao X, Wang Z, Li T, Zhang L, Lu Z, Long M, Wang Y, Wei G, Shen X. T6SS secretes an LPS-binding effector to recruit OMVs for exploitative competition and horizontal gene transfer. ISME J. 2022Feb;16(2):500-510 doi: 10.1038/s41396-021-01093-8. Epub 2021 Aug 25. PMID: 34433898; PMCID: PMC8776902

66. Suh JW, Kang JS, Kim JY, Kim SB, Yoon YK, Sohn JW. Characterization of the Outer Membrane Vesicles of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Exhibiting Growth Inhibition against Acinetobacter baumannii. Biomedicines. 2024Mar1;12(3):556 doi: 10.3390/biomedicines12030556. PMID: 38540169; PMCID: PMC10967770

67. Huang W, Meng L, Chen Y, Dong Z, Peng Q. Bacterial outer membrane vesicles as potential biological nanomaterials for antibacterial therapy. Acta Biomater. 2022Mar1;140:102-115 doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2021.12.005. Epub 2021 Dec 9. PMID: 34896632

68. Li Z, Clarke AJ, Beveridge TJ. Gram-negative bacteria produce membrane vesicles which are capable of killing other bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1998Oct;180(20):5478-83 doi: 10.1128/JB.180.20.5478-5483.1998. PMID: 9765585; PMCID: PMC107602

69. Cooke AC, Nello AV, Ernst RK, Schertzer JW. Analysis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm membrane vesicles supports multiple mechanisms of biogenesis. PLoS One. 2019Feb14;14(2):e0212275 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0212275. PMID: 30763382; PMCID: PMC6375607

70. Zhou Z, Sun L, Tu Y, Yang Y, Hou A, Li J, Luo J, Cheng L, Li J, Liang K, Yang J. Exploring Naturally Tailored Bacterial Outer Membrane Vesicles for Selective Bacteriostatic Implant Coatings. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2024Oct;11(39):e2405764 doi: 10.1002/advs.202405764. Epub 2024 Aug 21. PMID: 39166390; PMCID: PMC11497020

71. Huang Y, Sun J, Cui X, Li X, Hu Z, Ji Q, Bao G, Liu Y. Enhancing protective immunity against bacterial infection via coating nano-Rehmannia glutinosa polysaccharide with outer membrane vesicles. J Extracell Vesicles. 2024Sep;13(9):e12514 doi: 10.1002/jev2.12514. PMID: 39315589; PMCID: PMC11420661

72. Behrens F, Funk-Hilsdorf TC, Kuebler WM, Simmons S. Bacterial Membrane Vesicles in Pneumonia: From100 Mediators of Virulence to Innovative Vaccine Candidates. Int J Mol Sci. 2021Apr8;22(8):3858 doi: 10.3390/ijms22083858. PMID: 33917862; PMCID: PMC8068278

73. Ahmed AAQ, Besio R, Xiao L, Forlino A. Outer Membrane Vesicles (OMVs) as Biomedical Tools and Their Relevance as Immune-Modulating Agents against H. pylori Infections: Current Status and Future Prospects. Int J Mol Sci. 2023May10;24(10):8542 doi: 10.3390/ijms24108542. PMID: 37239888; PMCID: PMC10218342

74. Baker SM, Settles EW, Davitt C, Gellings P, Kikendall N, Hoffmann J, Wang Y, Bitoun J, Lodrigue KR, Sahl JW, Keim P, Roy C, McLachlan J, Morici LA. Burkholderia pseudomallei OMVs derived from infection mimicking conditions elicit similar protection to a live-attenuated vaccine. NPJ Vaccines. 2021Jan29;6(1):18 doi: 10.1038/s41541-021-00281-z. PMID: 33514749; PMCID: PMC7846723

75. Lim Y, Kim HY, Han D, Choi BK. Proteome and immune responses of extracellular vesicles derived from macrophages infected with the periodontal pathogen Tannerella forsythia. J Extracell Vesicles. 2023Dec;12(12):e12381 doi: 10.1002/jev2.12381. PMID: 38014595; PMCID: PMC10682907

76. Liu J, Kang R, Tang D. Lipopolysaccharide delivery systems in innate immunity. Trends Immunol. 2024Apr;45(4):274-287 doi: 10.1016/j.it.2024.02.003. Epub 2024 Mar 16. PMID: 38494365

77. Robison SG, Leman RF. Association of Group B Meningococcal Vaccine Receipt With Reduced Gonorrhea Incidence Among University Students. JAMA Netw Open. 2023Aug1;6(8):e2331742 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.31742. PMID: 37651146; PMCID: PMC10472183

78. Juodeikis R, Martins C, Saalbach G, Richardson J, Koev T, Baker DJ, Defernez M, Warren M, Carding SR. Differential temporal release and lipoprotein loading in B. thetaiotaomicron bacterial extracellular vesicles. J Extracell Vesicles. 2024Jan;13(1):e12406 doi: 10.1002/jev2.12406. PMID: 38240185; PMCID: PMC10797578

79. Rath P, Hermann A, Schaefer R, Agustoni E, Vonach JM, Siegrist M, Miscenic C, Tschumi A, Roth D, Bieniossek C, Hiller S. High-throughput screening of BAM inhibitors in native membrane environment. Nat Commun. 2023Sep13;14(1):5648 doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-41445-w. PMID: 37704632; PMCID: PMC10499997

80. Xiao T, Ma Y, Zhang Z, Zhang Y, Zhao Y, Zhou X, Wang X, Ge K, Guo J, Zhang J, Li Z, Liu H. Tailoring therapeutics via a systematic beneficial elements comparison between photosynthetic bacteria-derived OMVs and extruded nanovesicles. Bioact Mater. 2024Feb26;36:48-61 doi: 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2024.02.025. PMID: 38434148; PMCID: PMC10904884

81. Kadurugamuwa JL, Beveridge TJ. Bacteriolytic effect of membrane vesicles from Pseudomonas aeruginosa on other bacteria including pathogens: conceptually new antibiotics. J Bacteriol. 1996May;178(10):2767-74 doi: 10.1128/jb.178.10.2767-2774.1996. PMID: 8631663; PMCID: PMC178010

82. Huang W, Zhang Q, Li W, Yuan M, Zhou J, Hua L, Chen Y, Ye C, Ma Y. Development of novel nanoantibiotics using an outer membrane vesicle-based drug efflux mechanism. J Control Release. 2020Jan10;317:1-22 doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2019.11.017. Epub 2019 Nov 15. PMID: 31738965

83. Burt M, Angelidou G, Mais CN, Preußer C, Glatter T, Heimerl T, Groß R, Serrania J, Boosarpu G, Pogge von Strandmann E, Müller JA, Bange G, Becker A, Lehmann M, Jonigk D, Neubert L, Freitag H, Paczia N, Schmeck B, Jung AL. Lipid A in outer membrane vesicles shields bacteria from polymyxins. J Extracell Vesicles. 2024May;13(5):e12447 doi: 10.1002/jev2.12447. PMID: 38766978; PMCID: PMC11103557

84. Jiang Y, Ma J, Long Y, Dan Y, Fang L, Wang Z. Extracellular Membrane Vesicles of Escherichia coli Induce Apoptosis of CT26 Colon Carcinoma Cells. Microorganisms. 2024Jul17;12(7):1446 doi: 10.3390/microorganisms12071446. PMID: 39065214; PMCID: PMC11279139

85. Peng C, Xu Y, Wu J, Wu D, Zhou L, Xia X. TME-Related Biomimetic Strategies Against Cancer. Int J Nanomedicine. 2024Jan4;19:109-135 doi: 10.2147/IJN.S441135. PMID: 38192633; PMCID: PMC10773252

86. Tiwari A, Trivedi R, Lin SY. Tumor microenvironment: barrier or opportunity towards effective cancer therapy. J Biomed Sci. 2022Oct17;29(1):83 doi: 10.1186/s12929-022-00866-3. PMID: 36253762; PMCID: PMC9575280

87. Irene C, Fantappiè L, Caproni E, Zerbini F, Anesi A, Tomasi M, Zanella I, Stupia S, Prete S, Valensin S, König E, Frattini L, Gagliardi A, Isaac SJ, Grandi A, Guella G, Grandi G. Bacterial outer membrane vesicles engineered with lipidated antigens as a platform for Staphylococcus aureus vaccine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019Oct22;116(43):21780-21788 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1905112116. Epub 2019 Oct 7. PMID: 31591215; PMCID: PMC6815149

88. Qing S, Lyu C, Zhu L, Pan C, Wang S, Li F, Wang J, Yue H, Gao X, Jia R, Wei W, Ma G. Biomineralized Bacterial Outer Membrane Vesicles Potentiate Safe and Efficient Tumor Microenvironment Reprogramming for Anticancer Therapy. Adv Mater. 2020Nov;32(47):e2002085 doi: 10.1002/adma.202002085. Epub 2020 Oct 5. PMID: 33015871

89. Mi Z, Yao Q, Qi Y, Zheng J, Liu J, Liu Z, Tan H, Ma X, Zhou W, Rong P. Salmonella-mediated blood-brain barrier penetration, tumor homing and tumor microenvironment regulation for enhanced chemo/bacterial glioma therapy. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2023Feb;13(2):819-833 doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2022.09.016. Epub 2022 Sep 25. PMID: 36873179; PMCID: PMC9978951

90. Jiang S, Fu W, Wang S, Zhu G, Wang J, Ma Y. Bacterial Outer Membrane Vesicles Loaded with Perhexiline Suppress Tumor Development by Regulating Tumor-Associated Macrophages Repolarization in a Synergistic Way. Int J Mol Sci. 2023Jul7;24(13):11222 doi: 10.3390/ijms241311222. PMID: 37446401; PMCID: PMC10342243

91. van der Pol L, Stork M, van der Ley P. Outer membrane vesicles as platform vaccine technology. Biotechnol J. 2015;10(11):1689-1706 doi:10.1002/biot.201400395

92. Gujrati V, Kim S, Kim SH, Min JJ, Choy HE, Kim SC, Jon S. Bioengineered bacterial outer membrane vesicles as cell-specific drug-delivery vehicles for cancer therapy. ACS Nano. 2014Feb25;8(2):1525-37 doi: 10.1021/nn405724x. Epub 2014 Jan 15. PMID: 24410085

93. Wang J, Zhao Y, Nie G. Intelligent nanomaterials for cancer therapy: recent progresses and future possibilities. Medical Review. 2023;3(4):321-342 https://doi.org/10.1515/mr-2023-0028

94. Jin M, Huo D, Sun J, Hu J, Liu S, Zhan M, Zhang BZ, Huang JD. Enhancing immune responses of ESC-based TAA cancer vaccines with a novel OMV delivery system. J Nanobiotechnology. 2024Jan3;22(1):15 doi: 10.1186/s12951-023-02273-8. PMID: 38166929; PMCID: PMC10763241

95. Ellis TN, Kuehn MJ. Virulence and immunomodulatory roles of bacterial outer membrane vesicles. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2010;74(1):81-94 doi:10.1128/MMBR.00031-09

96. Chen PP, Zhang JX, Li XQ, Li L, Wu QY, Liu L, Wang GH, Ruan XZ, Ma KL. Outer membrane vesicles derived from gut microbiota mediate tubulointerstitial inflammation: a potential new mechanism for diabetic kidney disease. Theranostics. 2023Jul9;13(12):3988-4003 doi: 10.7150/thno.84650. PMID: 37554279; PMCID: PMC10405836

97. Zhang L, Zhang D, Liu C, Tang B, Cui Y, Guo D, Duan M, Tu Y, Zheng H, Ning X, Liu Y, Chen H, Huang M, Niu Z, Zhao Y, Liu X, Xie J. Outer Membrane Vesicles Derived from Fusobacterium nucleatum Trigger Periodontitis Through Host Overimmunity. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2024Dec;11(47):e2400882 doi: 10.1002/advs.202400882. Epub 2024 Oct 30. PMID: 39475060; PMCID: PMC11653712

98. Schwechheimer C, Kuehn MJ. Outer-membrane vesicles from Gram-negative bacteria: biogenesis and functions. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2015Oct;13(10):605-19 doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3525. PMID: 26373371; PMCID: PMC5308417