Impact Factor

ISSN: 1449-1907

Int J Med Sci 2026; 23(3):1144-1160. doi:10.7150/ijms.124996 This issue Cite

Review

LIPUS as a potential strategy for anti-inflammation and repair: A review of the mechanisms

1. Hepatic Surgery Center, Tongji Hospital of Tongji Medical College of Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, Hubei, China; Hubei Key Laboratory of Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Diseases, Wuhan, China.

2. The Second Clinical Department, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China.

3. Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Internal Medicine at Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China.

4. Department of Medical Ultrasound, Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China.

*, These authors contributed equally to this work.

Received 2025-9-10; Accepted 2026-2-4; Published 2026-2-18

Abstract

Hundreds of millions of people worldwide endure continuous suffering and significant economic burdens due to inflammatory diseases. Various acute and chronic inflammatory diseases and the natural aging of the human body are common causes of organ damage. Therefore, how to reasonably regulate inflammation, tissue repair and regeneration after organ damage has been of great concern, especially the pathological repair caused by inflammation will lead to the destruction of the original structure and function of tissues and organs. Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound (LIPUS) is a promising non-invasive physical therapy that can produce different biological effects on organs, tissues and cells. Certain clinical trials have demonstrated the outstanding capacity of LIPUS in anti-inflammation and repair. Many in vivo and in vitro basic studies have also reported the molecular effect mechanisms by which LIPUS exerts capacity of anti-inflammation and repair. This review focuses on the molecular mechanism of LIPUS anti-inflammation and repair and emphasizes the crucial role of LIPUS in various diseases. In addition, we compile clinical trials to provide readers with a more thorough understanding of the current potential of LIPUS in inflammation control and organ function restoration.

Keywords: low-intensity pulsed ultrasound (LIPUS), inflammation, repair, signaling pathway, molecular mechanism

1. Introduction

The global burden of immune-mediated inflammatory diseases is severe. In 2019, approximately 67.58 million people were affected worldwide, leading to significant health impairments and socioeconomic consequences [1]. Chronic inflammatory diseases are recognized as the leading cause of death globally, with more than 50% of deaths attributed to inflammation-related disorders [2]. A variety of acute and chronic inflammatory diseases and the natural aging of the human body are common drivers of organ damage. Therefore, the rational regulation of inflammation, tissue repair, and regeneration after organ damage has always been a significant concern. In particular, the pathological repair induced by inflammation can destroy the original structure and function of tissues and organs, such as skin keloid, emphysema and pulmonary fibrosis, cirrhosis of the liver, glomerulosclerosis, or cerebral gliosis [3].

Current treatments for inflammatory diseases include antibiotics, steroids, and immunosuppressive drugs, which are usually administered systemically [4]. Despite advances in existing targeted therapies, patient remission rates remain suboptimal, and achieving sustained remission without medication remains an unmet clinical need [1]. For instance, in 2021, over 22% of adults over 40 had knee osteoarthritis, with end-stage patients often requiring joint replacement. Currently, no cure exits for osteoarthritis. Clinical treatments traditionally focus on symptom relief rather than halting disease progression [5]. Consequently, there is an urgent need to develop novel therapeutic strategies.

Low intensity pulsed ultrasound (LIPUS) is widely regarded as a non-invasive physical therapy. Due to its relatively low intensity, the thermal effects of LIPUS are negligible [6]. An increasing body of evidence demonstrates that LIPUS possesses potent anti-inflammatory properties and significantly promotes the structural and functional repair of tissues and organs [7-10]. Given its therapeutic efficacy, targeted approach, non-invasiveness, and convenience, LIPUS represents an ideal modality for anti-inflammation and repair. Recent studies suggest that LIPUS holds significant promise for both anti-inflammatory and tissue protection. For instance, Li et al. [11] highlighted the major molecular mechanisms through which LIPUS exerts anti-inflammatory effects.

Key molecules and cell process are involved in both the inflammatory response and the protection and restoration of organ structure and function. These include focal adhesion kinase (FAK) [12], brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) [13] and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) [14]. Furthermore, LIPUS regulates many of these shared key molecules. However, comprehensive reviews addressing this dual role are lacking. Therefore, this review summarizes the molecular mechanisms by which LIPUS therapy facilitates both anti-inflammation and tissue repair, exploring its potential in treating various diseases. LIPUS has been shown to inhibit inflammation and fibrosis in conditions such as chronic prostatitis [15], osteoarthritis [16], cardiovascular diseases [10, 17], and renal injuries [18]. In neuro-related disorders, it supports nerve repair [19], and it also aids in the healing of periodontal tissue [19], muscle [20], and tendon injuries [21]. Additionally, we compile clinical trials to provide a thorough understanding of the current potential of LIPUS in inflammation control and organ function restoration. It also concludes with a summary of its limitations and several prospects to promote further research in the field of LIPUS-mediated anti-inflammatory and reparative effects.

2. Therapeutic Ultrasound and LIPUS

Ultrasound is a form of mechanical characterized by sound pressure waves with frequencies beyond the limitation of human hearing (i.e. 20 to 20,000 Hz). It plays a vital role in modern medicine, serving not only as a diagnostic imaging modality but also as a therapeutic treatment [22]. In therapeutic applications, ultrasound functions through both thermal and non-thermal mechanisms. The latter include ultrasonic cavitation, gas activation, mechanical stress, and other indeterminate non-thermal processes [23]. Typically generated by piezoelectric sensors that convert electrical energy into mechanical force, LIPUS periodic waves propagate through the medium into target tissues. This causes vibration and impact, producing mechanical stimuli that promote biochemical events facilitating anti-inflammation and repair [10, 24, 25].

During this process, cavitation, acoustic streaming, and mechanical stimulation serve as the primary non-thermal effects of LIPUS, generating microbubbles and microjets to achieve therapeutic results [26]. This non-thermal mechanism can also be explained by acoustic streaming effect during LIPUS exposure. Acoustic streaming may alter the local cellular microenvironment, influencing intracellular potassium and calcium content [27]. These events impact the plasma membrane, focal adhesions, and cytoskeletal structures, thereby initiating intracellular signal transduction. Although the sensor molecules responsible for initially detecting these mechanical stimuli are not fully understood, we will discuss mechanosensitive structures that potentially play a role.

Generally, ultrasound is widely used in imaging medicine at intensities of 0.05-0.50W/cm2 [28]. According to intensity, therapeutic ultrasound can be divided into two groups: low-intensity ultrasound (<3 W/cm2), and high-intensity ultrasound (≥3 W/cm2). Additionally, ultrasound is categorized into three ranges based on ultrasound frequency: high-frequency ultrasound (1-20 MHz) for medical diagnostic applications, medium-frequency ultrasound (0.7-3.0 MHz) for therapeutic medicine, and low-frequency (LF) ultrasound (20-200 kHz) for industrial and therapeutic applications [29]. Typical pulse ratios of pulse duration to pulse rest time are 1:5 [6].

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved therapeutic ultrasound for two main clinical areas: thermal applications (including physical therapy, thermotherapy, and high-intensity focused ultrasound for tissue ablation) and non-thermal applications (including extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy, intracorporeal lithotripsy, and low-power kilohertz frequency devices) [22]. LIPUS is a type of mid-frequency ultrasound (0.7-3 MHz) that is output in a pulsed-wave mode (100 and 1000 Hz) [30]. Other parameters of LIPUS therapies include the ultrasound intensity ranging from 0.02-1 W/cm2 (spatial average temporal average, SATA) and a treatment duration of 5-20 minutes daily [31]. Researchers typically use LIPUS at an intensity of 30 mW/cm² SATA, a frequency of 1.5 MHz, and a 1 kHz pulse repetition rate with a 20% duty cycle [30].

A growing number of clinical studies are currently investigating LIPUS therapy. For instance, in 2023, Li et al. [32] conducted a single-center, small-sample, exploratory clinical study on patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. Results showed improvements in C-reactive protein, interleukin-6, leukocytes, and fingertip arterial oxygen saturation (SaO2) after an average of 7.2 days of LIPUS treatment. This therapy reduced lung inflammation and serum inflammatory factor levels, attenuating pneumonia. Although LIPUS has demonstrated promising clinical results in anti-inflammation and repair, its specific mechanisms remain unclear. Recent studies have begun exploring these molecular mechanisms, providing a theoretical basis for broader clinical applications.

3. Biological and Molecular Mechanisms of LIPUS for anti-inflammation and repair

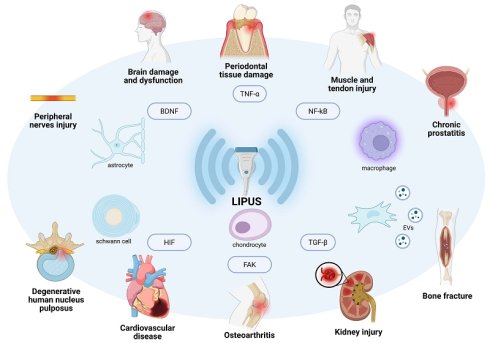

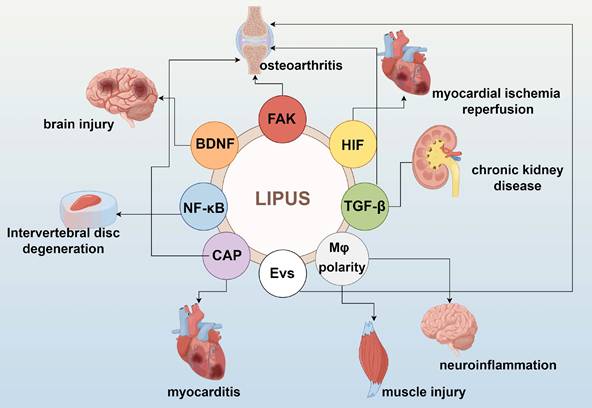

LIPUS serves as a modulator of the tissue microenvironment and immune cell infiltration. Significant data from basic studies, both in vivo and in vitro, have accumulated regarding the role of LIPUS in anti-inflammation and repair. LIPUS exerts its anti-inflammatory and reparative effects by mechanically perturbing cells and tissues, triggering a cascade of biological responses. These include the activation of mechanosensitive pathways, regulation of inflammatory signaling, and modulation of immune cell phenotypes (Figure 1). In this section, we elucidate the biological and molecular applications of LIPUS in anti-inflammation and repair (Table 1) (Figure 2, 3).

The mechanical effects of LIPUS activate intracellular downstream pathways by affecting the structure of the cell membrane surface, the permeability of ion channels, and cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions [33]. Recently, Piezo1 proteins have been identified as Ca2+ channels on various cell surfaces and play important roles as biomechanical transducers [34]. In 2021, Zhang et al. [35] demonstrated that Piezo1 transduces LIPUS-associated mechanosignals into the cell via Ca2+ influx. This acts as a second messenger, activating extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2) phosphorylation and perinuclear F-actin polymerization to regulate the proliferation of mouse calvaria osteoblast-like cells. Furthermore, LIPUS stimulation increases cilia length in chondrocytes and affect the orientation of primary cilia in chondrocytes. This changes in cilia length and shape are reversible and may be associated with ERK1/2 activation [36]. Direct cell-to-cell communication is also important for mechanotransduction [19]. Another potential mechanism involves the initial activation of integrins in order to convert the mechanical energy of LIPUS [37].

Molecular and cellular processes involved in the LIPUS bioeffects. By Figdraw. Abbreviations: BDNF: brain-derived neurotrophic factor; CAP: cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway; EVs: extracellular vesicles; FAK: focal adhesion kinase; HIF: hypoxia-inducible factor; NF-κB: nuclear factor-κB.

The application of LIPUS in anti-inflammation and repair in vivo and in vitro studies

| Mechanism | Sources | Year | LIPUS parameters | Cell | Pathway | Animal model | Disease | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intensity (mW/cm2) | Frequency (MH) | Time | Total time | |||||||

| FAK | Xia et al. [37] | 2015 | 40 | 3 | 20min | 6 weeks | N/A | integrin/FAK/ MAPK | OA rabbit model | OA |

| Jang et al. [41] | 2014 | 27.5 | 3.5 | 5min | N/A | CPC | SFKs/FAK | N/A | PTOA | |

| Xia et al. [19] | 2019 | 500/300 | 1 | 10/5min | 4 days | iPSCs-NCSCs | FAK/ERK1/2 | N/A | sciatic nerve injury | |

| Sato et al. [74] | 2014 | 30 | 3 | 20min | N/A | Rabbit knee synovial membrane cell | integrin/FAk/ MAPK | N/A | RA | |

| Chen et al. [12] | 2019 | 30 | 0.25 | 20min | 2days | BMSCs | FAK/ERK1/2 | N/A | femoral defects | |

| Zhang et al. [42] | 2016 | 30 | 1.5 | 20min | 1week | human NP cell | FAK/PI3K/Akt | N/A | IVD degeneration | |

| BDNF | Liu et al. [45] | 2017 | 110 | 1 | 5min | 15min | rat astrocyte cell | TrkB-Akt and Calcium-CaMK | N/A | neurodegenerative diseases |

| Su et al. [78] | 2017 | 528 | 1 | 5min | 3days | N/A | TrkB/AKt-CREB | TBI model | TBI | |

| Li et al. [13] | 2023 | 300/80 | 1 | 10min | 3weeks | Schwann cells | TrkB/Akt/ CREB | bilateral cavernous nerve injury rat | cavernous nerve injury-induced neurogenic erectile dysfunction | |

| TGF-β | Lei et al. [101] | 2015 | 200/300 | 1.7 | 3min | 2weeks | N/A | TGF-β1/ Smad/CTGF | ED diabetic rat | diabetic ED |

| Yi et al. [14] | 2020 | 30 | 1 | 20min | 3/6weeks | N/A | TGF-β1/Smad3 | Rabbit TMJOA model | TMJOA | |

| Ouyang et al. [18] | 2020 | 60 | 1 | 20min | 4weeks | N/A | Nrf2/keap1/HO-1 and TGF-β1/Smad | CKD rats | CKD | |

| Yang et al. [87] | 2014 | 90 | 1.5 | 20min | 13days | HPDLC | BMP-Smad | N/A | Fracture healing and osteogenic differentiation | |

| Bernal et al. [9] | 2015 | 83 | 5 | 15min | N/A | CMAs | BMP-Smad | N/A | ischemic heart disease | |

| HIF | Cao et al.[10] | 2023 | 500 | 1 | 20min | 3days | N/A | ASK1/JNK | MI/R rat | MI/R |

| Zhao et al. [17] | 2021 | 77.2 | 0.5 | 20min/ days | 5weeks | N/A | HIF-1α/DNMT3a | TAC rat | cardiac fibrosis | |

| Yang et al. [48] | 2020 | 45 | 1 | 20min | 4weeks | Chondrocyte | HIF-1α/HIF-2α | TMJ injury induced by CSD | Temporomandibular disorders | |

| NF-κB | Zhang et al. [59] | 2017 | 60 | 1.5 | 120min | N/A | U937 cells(macrophage) | TLR4-NF-κB | N/A | N/A |

| Nagao et al. [76] | 2017 | 30 | 1.5 | 30min | N/A | MC3T3-E1 | AT1-PLCβ | N/A | N/A | |

| Sato et al. [53] | 2015 | 30 | 1.5 | 20min | 2weeks | Human salivary gland acinar and ductal cells | upregulates expression of AQP5 and inhibits TNF-α production | N/A | Xerostomia | |

| Zhao et al. [55] | 2017 | 200 | 1.5 | 20min | 3/4times | polyethylene debris induced RAW 264.7 cell | FBXL2-TRAF6 | N/A | periprosthetic inflammatory loosening | |

| Yi et al. [56] | 2021 | 30 | 1.5 | 20min | 3days | NP cell | NF-κB | N/A | Intervertebral disc degeneration | |

| CAP | Liu et al. [90] | 2023 | N | 1 | 12min | 15dys | N/A | N/A | Autoimmune myocarditis mouse | myocarditis |

| Zachs et al. [75] | 2019 | N | 1 | 20min | N/A | N/A | N/A | OA mouse model | OA | |

| EVs | Liao et al. [73] | 2021 | 30 | 1.5 | 20min | 4weeks | N/A | NF-κB | OA rat | OA |

| Li et al. [61] | 2023 | 300 | 1 | 15min | N/A | BMSCs | MAPK | N/A | inflammation | |

| Li et al. [62] | 2018 | 30 | 1.5 | 12h | N/A | BMDCs | TNF-α | N/A | atherosclerosis | |

| Ye et al. [86] | 2023 | 80 | 1 | 10min | 3times | SC | PI3K/Akt/FoxO | BCNI-induced ED rat | NED | |

| Macrophage polarity | Zhang et al. [102] | 2019 | 30 | 1.5 | 20min/ day, 5days/week | 2weeks | N/A | N/A | rat model of spinal fusion | inflammation in spinal fusion |

| Silva et al. [20] | 2017 | 40 | 1 | 3min | 7days | N/A | N/A | cryoinjury of the right TA muscle rat | muscle injuries | |

| Hsu et al. [80] | 2023 | 30 | 1 | 5min | 15min | microglial cell | STAT1/STAT6/ PPARγ | N/A | Neuroinflammation | |

Abbreviation: FAK: focal adhesion kinase; MAPK: mitogen-activated protein kinase; NF-κB: nuclear factor-κB; OA: osteoarthritis; PTOA: posttraumatic osteoarthritis; CPC: chondrogenic progenitor cell; SFKs: Src family kinases; ERK1/2: extracellular regulated protein kinases 1/2; PI3K: phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; iPSCs-NCSCs: induced pluripotent stem cells-derived neural crest stem cells; RA: rheumatoid arthritis; NP: nucleus pulposus; IVD: intervertebral disk; BDNF: brain-derived neurotrophic factor; TrkB: tyrosine Kinase receptor B; CaMK: calcium/calmodulin stimulated protein kinase; CREB: cyclic-AMP response binding protein; TBI: traumatic brain injury; TGF-β: transforming growth factor-β; CTGF: connective tissue growth factor; Nrf2/keap1/HO-1: nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2/the Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1/heme oxygenase 1; ED: erectile dysfunction; HPDLC: human periodontal ligament cell; TMJOA: temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis; CKD: chronic kidney disease; CMAs: Cardiac mesoangioblasts; HIF: hypoxia-inducible factor; ASK1: apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1; JNK: c-Jun N-terminal kinase; DNMT3a: DNA methyltransferase 3 α; MI/R: myocardial ischemia/reperfusion; TAC: transverse aortic constriction; CSD: chronic sleep deprivation; TLR4: toll like receptor 4; AT1: angiotensin type 1 receptor; PLCβ: phospholipase C β; AQP5: aquaporin Protein-5; FBXL2: F-box and leucine rich repeat protein 2 gene; TRAF6: TNF receptor associated factor 6; FoxO: Forkhead Box O; TMJ: temporomandibular joint; BMSCs: bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells; BMDCs: bone marrow dendritic cells; SC: Schwann cell; CAP: cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway; BCNI: bilateral cavernous nerve crush injury; NED: neurogenic ED; TA: tibialis anterior; EVs: extracellular vesicles; TNF-α: tumor necrosis factor α; PPARγ: peroxisome proliferator activated receptor γ; STAT1: signal transducer and activator of transcription 1; MC3T3-E1: mouse calvaria osteoblast-like cells; N/A: not applicable.

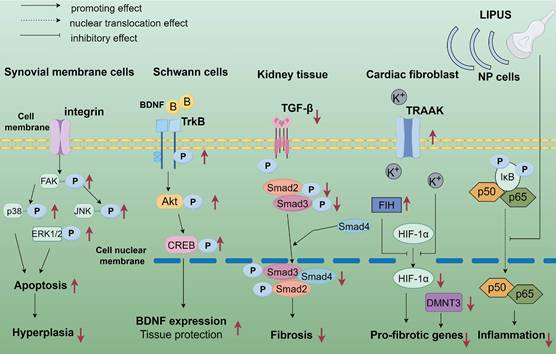

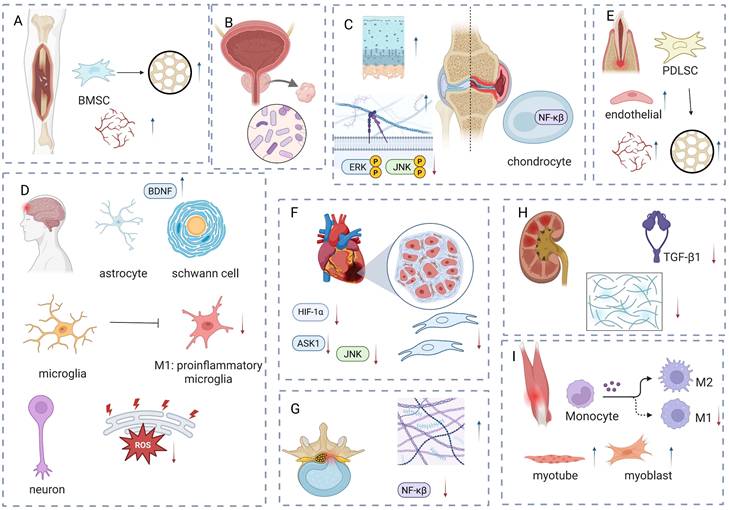

The application of LIPUS in anti-inflammation and repair at the biological and molecular level. LIPUS up-regulated phosphorylated FAK in synovial cells, leading to decreased ERK, c-JNK, and p38 phosphorylation. LIPUS modulated apoptosis and survival of osteoarticular synoviocytes through the integrin/FAK/MAPK signaling pathway. LIPUS activates SCs through the TrkB/Akt/CREB axis in peripheral nerves, enhancing SCs proliferation, migration, and nerve growth factor expression. In an adriamycin-induced chronic renal injury model, LIPUS treatment significantly ameliorated renal injury by blocking signaling between TGF-β1 and its downstream molecules, Smad2 and Smad3 to reduce fibrosis and inflammation. LIPUS partially mitigated hypoxia-induced cardiac fibroblast phenotypic changes through the TRAAK-mediated HIF-1α/DNMT3a signaling pathway. In LPS-induced NP cells, LIPUS inhibited the NF-κB signaling pathway by suppressing p-P65 protein expression and P65 translocation to the nucleus, i.e., inhibiting the NF-κB signaling pathway, inflammation, and catabolism in LPS-induced human degenerative medulla oblongata cells. By Figdraw. Abbreviation: CREB: cyclic-AMP response binding protein; DNMT3a: DNA methyltransferase3α; ERK: extracellular regulated protein kinases; HIF: hypoxia-inducible factor; JNK: c-Jun N-terminal kinase; LIPUS: low intensity pulse ultrasound; MAPK: mitogen-activated protein kinase; NF-κB: nuclear factor-κB; NP: nucleus pulposus; SCs: Schwann cells; TrkB: tyrosine Kinase receptor B; TGF-β: transforming growth factor-β; TRAAK: TWIK-related arachidonic acid-activated K+ channel.

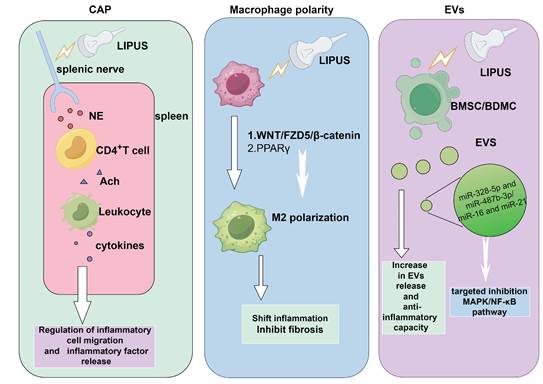

The capacity of LIPUS in anti-inflammation and repair via multiple signaling pathways. NE released from the splenic nerve treated by LIPUS stimulated CD4+ T cells to release ACh, making leukocytes releasing cytokines. This could modulate inflammatory cells migration and inflammatory factors release. EVs produced by LIPUS-treated BMSCs contained higher levels of miR-328-5p and miR-487b-3p, targeting genes in the MAPK signaling pathway. LIPUS treatment increased miR-16 and miR-21 levels in BMDC exosomes, targeting and inhibiting the NF-κB signaling pathway. The WNT/FZD5/β-catenin axis and PPARγ signaling pathway were encential for LIPUS to promote M2 polarization. By Figdraw. Abbreviation: Ach: acetylcholine; BMSCs, bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells; BMDC: bone dendritic cell; CAP: cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway; EVs: extracellular vesicles; LIPUS: low intensity pulse ultrasound; MAPK: mitogen-activated protein kinase; NF-κB: nuclear factor-κB; NE: Norepinephrine; PPARγ: peroxisome proliferator activated receptor γ.

LIPUS coordinates anti-inflammatory and repair responses through multiple molecular pathways. FAK, a non-receptor tyrosine kinase, plays a key role in integrin-mediated signaling, regulating cell adhesion migration, proliferation, and survival [38, 39]. Sato et al. [19] reported that LIPUS transmits signals intracellularly via integrins acting as mechanoreceptors. LIPUS controls cell spreading on fibronectin through the FAK-Rab5-Rac1 pathway [40]. Under LIPUS irradiation, FAK is phosphorylated via vinculin; subsequent FAK signaling leads to Rab5-dependent Rac1 activation, promoting actin cytoskeleton rearrangement and increased cell motility [40]. Phosphorylation of FAK activated multiple signaling pathways by LIPUS exposure, such as integrin/FAK/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) [37], Src family kinases (SFKs) [41], FAK/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt [42].

BDNF, synthesized in neurons and glial cells, is vital for neuronal differentiation, cell survival, and synaptic function in the nervous system [43]. BDNF is sustainably released through a Ca2+ - dependent mechanism, binding strongly to tropomyosin receptor kinase B (TrkB) receptors to activate signaling pathways [44]. LIPUS stimulation increased BDNF expression in astrocytes through TrkB/PI3K/Akt, TrkB/phospholipase C (PLC) - γ/Ca2+, and calcium/calmodulin stimulated protein kinase (CaMK) signaling pathways [45]. BDNF levels can also be elevated through TrkB/Akt/CREB signaling pathway by LIPUS application [13].

Chronic inflammation, fibrosis, and cancer are common TGF-β-related diseases [46]. LIPUS application generally attenuated fibrosis by inhibiting the TGF/Smad pathway [14, 24]. Treatment with LIPUS blocks TGF-β1 and its downstream molecules, Smad2 and Smad3, as well as the nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2/Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1/heme oxygenase 1 (Nrf2/keap1/HO-1) pathway, thereby reducing fibrosis and inflammation [18].

Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) orchestrates cellular adaptation to low oxygen levels by controlling metabolic, angiogenic, and erythropoietic transcriptional programs [47]. Given the heart's high oxygen demand for pumping blood, LIPUS holds promise for combating hypoxia-related inflammation [48]. It reduces cardiac fibrosis by decreasing HIF-1α expression and suppressing ASK1 and JNK [10]. Additionally, it protects against myocardial ischemia/reperfusion (MI/R) through the TWIK-related arachidonic acid-activated K+ channel (TRAAK)-mediated HIF-1α/DNA methyltransferase3α (DNMT3a) signaling pathway [17]. By mitigating the hypoxic response, LIPUS reduces downstream harmful effects such as oxidative stress, inflammation, and fibrosis [17]. This represents a direct molecular intervention at the level of hypoxia signaling, distinct from some therapies based on enhancing oxygen's physical diffusion [49].

The cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway (CAP) is a neuro-immunomodulatory mechanism in the central nervous system that swiftly regulates systemic inflammatory responses. Norepinephrine (NE) released from the spleen stimulates CD4+ T cells to release acetylcholine (ACh), binding to the α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (α7nAChR) on macrophages. The vagus nerve (VN) attenuates inflammatory responses in several systems by inhibiting splenic macrophages, including the lungs, digestive tract, myocardium, synovium, and kidneys [50]. In colitis, Nunes et al. [51] reported that therapeutic ultrasound applied to the mouse abdomen activated the vagus nerve, splanchnic nerve, and CAP, inhibiting pro-inflammatory cytokine release. Furthermore, ACh released from enteric neurons to muscle macrophages in the intestine affected the colon and mesenteric lymph nodes (MLN), eliciting an anti-inflammatory response that alleviated dextran sodium sulfate (DSS)-induced colitis.

Regulating NF-κB transcriptional activity involves multiple mechanisms including ubiquitination, sumoylation, or phosphorylation of upstream and downstream mediators, IκB kinase (IKK) subunits, or NF-κB proteins themselves [52]. Sato et al. [53] showed that LIPUS activates intracellular ubiquitin-editing protein A20 in response to inflammatory stimuli. This activates a negative feedback system in salivary gland acini and ductal cells to inhibit the NF-κB pathway and promote an anti-inflammatory response. Similarly, tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor associated factor 6 (TRAF6), an E3 ubiquitin ligase, activates the NF-κB pathway by linking to the K63-linked polyubiquitin chain, subsequently facilitating IKK complex activation [54]. LIPUS induces the expression of F-box and leucine rich repeat protein 2 gene (FBXL2), mediates TRAF6 ubiquitination, reduces TRAF6 and NF-κB levels and inhibits the downstream inflammatory signaling pathway [55]. Additionally, LIPUS suppresses p-P65 protein expression and P65 translocation to the nucleus, inhibiting the NF-κB pathway [56].

LIPUS directly modulates immune cell behavior and optimizes the microenvironment. Activated macrophages are typically classified into M1 and M2 types, influenced by factors such as microbes, the tissue environment, and cytokine signals. Excessive M1 activity drive chronic inflammation and inflammatory diseases. M2 macrophages are key to tissue repair and immune tolerance [57]. Rational spatiotemporal modulation of macrophage polarization can be achieved through LIPUS, reducing inflammation and inhibiting fibrosis [58]. Moreover, continuous LIPUS mechanical force suppressed toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) mRNA levels in LPS-induced macrophages and inhibited degradation and phosphorylation of IκBα and p65 nuclear translocation [59]. Notably, TLR4 protein expression showed no significant difference with or without LIPUS, suggesting a possible impact on TLR4 gene transcription rather than direct down-regulation of the existing receptor. Zhao et al. [55] found that LIPUS induces the expression of F-box/FBXL2, reduces TRAF6/NF-κB levels and inhibites the downstream inflammatory signaling pathway in macrophage.

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are membrane-encapsulated particles produced by nearly all cell types that serve as a pathway for intercellular communication [60]. The increased production of LIPUS-mediated EVs, along with the greatly enhanced anti-inflammatory and repair capabilities, holds great promise for the engineered production and application of EVs. Li et al. [61] demonstrated that LIPUS stimulation increased EVs release from BMSCs by 3.66-fold. It promoted proliferation, EVs secretion, and anti-inflammatory functions of BMSCs without affecting cell morphology and apoptosis. EVs produced by LIPUS-treated BMSCs (LIPUS-EVs) contained higher levels of miR-328-5p and miR-487b-3p compared to those from non-LIPUS-treated BMSCs and exerted anti-inflammatory functions by targeting genes in the MAPK signaling pathway. When cultured with RAW264.7 cells, LIPUS-EVs induced higher anti-inflammatory factor (IL-10) expression and lower NF-κB signaling activity in response to LPS. In vivo, mice injected with LIPUS-EVs exhibited higher allogeneic skin IL-10 expression, lower pro-inflammatory factor (IL-6) expression, and reduced immune cell infiltration. Thus, both in vitro and in vivo experiments demonstrate that LIPUS enhances the anti-inflammatory effects of BMSC-derived EVs. Similarly, Li et al. [62] found that LIPUS treatment increased miR-16 and miR-21 levels in barrow bone dendritic cell (BMDC) exosomes, targeting and inhibiting the NF-κB signaling pathway.

4. Application of LIPUS for anti-inflammation and repair

LIPUS has been used clinically in various contexts, with an increasing number of clinical trials and animal experiments revealing its potential for use in anti-inflammation and repair (Table 2, Figure 4). In inflammation-related diseases such as chronic prostatitis, osteoarthritis, cardiovascular diseases, and renal injuries, LIPUS can alter microbial communities, regulate cell metabolism and signaling pathways, and inhibit inflammation and fibrosis to exert therapeutic effects. In neuro-related disorders such as brain dysfunction and peripheral nerve injuries, LIPUS promotes neurogenesis, regulates cell activity, and gene expression to support nerve repair. It also aids in repair periodontal tissue damage, muscle, and tendon injuries by regulating cell differentiation and intercellular communication.

4.1 Bone fracture

In 1994, the FDA approved LIPUS for clinical use in the repair of fresh fractures [63]. In 2017, Leighton R et al. reported a healing rate of over 80% for LIPUS treatment of 1441 cases of non-union fractures (at least 3 months old) at various anatomical sites [64]. Padilla et al. and McCarthy et al. reviewed the application of ultrasound in bone repair, focusing on LIPUS. They discussed dosage standardization and the potential thermal and non-thermal biological effects on bone healing, including effects on gene expression, signaling molecules, mechanotransduction pathways, and the extracellular environment [65, 66].

Yao et al. [67] prepared nanomechanical force generators and explored their combined effects with LIPUS on osteogenesis in BMSCs. LIPUS was applied at 3 MHz frequency, 50% duty cycle, and appropriate intensity of 100mW/cm2. The combination of LIPUS and nanomechanical force generators promotes osteogenesis and bone formation in BMSCs by modulating transient receptor potential melastatin 7 (TRPM7), the actin cytoskeleton, and intracellular calcium oscillations. The specific mechanism involves nanomechanical force generators binding to integrin receptors on the BMSC membrane, transmitting LIPUS mechanical effects, and inducing changes in TRPM7 activity to enhance extracellular calcium influx.

A study on 40 patients with anterior mandibular fractures assessed the effect of LIPUS on healing. Patients were randomly assigned to a control group (20 cases) or a treatment group (20 cases), both receiving standard surgery. The treatment group received LIPUS (1.5 MHz, 30 mW/cm², 20 minutes daily) on days 4, 8, 14, and 20 post-surgery. Results showed significantly better pain relief, wound healing, and fracture healing scores in the treatment group. At 12 weeks, 60% of the treatment group had complete healing, compared to 15% in the control group [68]. In another study on delayed fibular fracture healing, 13 patients (9 women, 4 men) were divided into LIPUS treatment (7 cases) and control groups (6 cases). LIPUS was applied daily for 20 minutes with parameters of 1.5 MHz frequency, 1 kHz modulation, and 30 mW/cm2 peak pressure for 5 months. Histological and morphometric analysis showed that LIPUS increased small blood vessels in the newly formed bone, with a 70% increase in vessel size and trends of increased vascular density [69].

Clinical trials published in the last decade on the role of LIPUS in anti-inflammatory and repair

| Ref. | Study Type | Study Subjects | Interventions |

|---|---|---|---|

| [69] | Randomized prospective double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial | 13 patients with a delayed-union of the osteotomized fibula (9 females and 4 males, aged 42 - 63) | LIPUS application: 20 minutes per day for 5 months (intensity: 30mW/cm², burst width: 200μs, frequency: 1.5MHz) |

| [103] | Single-blind RCT | 150 orthodontic patients (aged 18 - 25) | LIPUS therapy: frequency: 1.6MHz, an average output intensity: 0.2W/cm² for 20 minutes each time (5 minutes for each first molar), with 3 doses |

| [104] | Prospective cohort study | 21 patients undergoing IVRO surgery (6 males and 15 females, aged 16 - 54) | LIPUS therapy: Started 2 days after surgery, received daily 20-minute LIPUS treatment for 3 weeks (intensity: 30mW/cm², burst width: 200ms, frequency: 1.5MHz) |

| [105] | Randomized, open-label, parallel-group, non-inferiority clinical trial | 323 patients with mild-to-moderate ED (aged 20 - 60) | Three times per week (3/W) and twice per week: Used a LIPUS treatment with a frequency of 1.7MHz, intensity of 0.3W/cm², a pulse duration time to pulse rest time ratio of 1:4 (200:800ms), 1000Hz for 5 minutes on each side of the penile shaft and crus in turn for a total of 20 minutes per treatment session |

| [68] | Randomized controlled clinical trial | 40 patients with mandibular fractures (34 males and 6 females, aged 20 - 40 years, ASA II) | Received LIPUS treatment (1.5MHz, 30mW/cm²) on postoperative days 4, 8, 14, and 20 for 20 minutes daily |

| [106] | Multicenter, double-blind, parallel RCT | 44 patients with Buerger disease and limb ischemia (aged ≥20 years and <65 years, Fontaine III) | Received 20-minute LIPUS treatment once a day for 24 weeks (2.0 MHz pulse signal, 200-second pulse train, 1 kHz repetition rate, intensity of 30 mW/cm², and a duty cycle of 20%) |

| [107] | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | 106 patients with bilateral KOA (aged ≥40 years, Kellgren & Lawrence II - III) | Received FLIPUS (frequency 0.6MHz, pulse repetition frequency 300Hz, spatial and temporal average intensity 120mW/cm², duty cycle 20%) treatment for 20 minutes a day for 10 days |

| [108] | Prospective, randomized, controlled, observer-blinded study | 114 patients with knee osteoarthritis (aged ≥40 years, Kellgren - Lawrence I - III) | Received FLIPUS (parameters same as in Document 7) treatment for 20 minutes a day for 12 days |

| [109] | Prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study | 50 client-owned dogs with naturally occurring unilateral cranial cruciate ligament rupture | Received 20-minute LIPUS treatment daily (1.5MHz, 30mW/cm², 1kHz pulse, 20% duty cycle) for 12 weeks after tibial plateau leveling osteotomy |

| [110] | Prospective, randomized, single-blind (assessor), controlled study | 40 patients aged 45 - 85 years with painful knee OA | Received TENS treatment or LIPUS combined with TENS treatment |

| [32] | RCT | 62 patients diagnosed with COVID - 19 pneumonia | Received LIPUS (572 kHz, 50 Hz, 820 mW/cm², 50% duty cycle), twice daily for 30 minutes during hospitalization |

| [111] | Prospective, RCT | 60 patients with concurrent ED and CP/CPPS | LIPUS treatment or drug therapy with tadalafil and doxazosin or LIPUS combined with tadalafil and doxazosin. Treatment duration was four weeks |

| [100] | Systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs | Seven RCTs with a total of 172 patients undergoing distraction osteogenesis | LIPUS treatment compared with sham devices or no devices |

| [93] | Double-blinded, randomized, and placebo-controlled study | 25 patients with Buerger disease (12 in the LIPUS group and 13 in the control group) | Received 20-minute LIPUS treatment daily for 24 weeks |

| [112] | RCT | 45 patients aged 10.5 - 14 years with skeletal class II division 1 malocclusion | Received LIPUS treatment |

| [113] | Prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled, single-blind trial | 96 patients initially diagnosed with knee osteoarthritis | Intraarticular HADMSCs injection and LIPUS therapy |

| [114] | Single blind randomized controlled trial | 100 female volunteers with chronic non-specific low back pain | Received Pulsed Laser (3J/cm²) or Pulsed Ultrasound (1W/cm², 3MHz) or Continuous Ultrasound (1W/cm², 1MHz) |

| [115] | Single blinded RCT | 60 participants with grades II and III KOA | Received HILT and ET or LIPUS and ET or only ET |

| [116] | Systematic review and meta-analysis | 26 randomized controlled trials with patients having fracture or osteotomy | LIPUS vs sham device or no device |

| [91] | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot trial | Patients with refractory angina without indication of PCI or CABG | Received LIPUS treatment or placebo |

| [117] | Multicenter double-blind randomized control trial | 62 adult patients undergoing limb lengthening or bone transport by distraction osteogenesis | Received active ultrasound device or placebo device |

| [118] | RCT | 34 patients with early-stage lumbar spondylolysis | Received LIPUS and RPT or only RPT |

| [119] | Randomized, blinded, sham controlled clinical trial | 501 patients with operatively managed tibial fractures | Received LIPUS treatment |

| [120] | Clinical trial | 72 patients with TMD (36 with masticatory myositis, 36 with synovitis) | LIPUS treatment for both groups |

| [85] | Single-site, prospective, double-blind, RCT | 48 participants with clinically confirmed PD | Received LIPUS treatment (600 kHz, 1.0 W/cm2, 50% duty cycle, 30 min/day for 4 months) |

| [121] | Meta-analysis | 288 participants from 5 RCTs on knee OA | LIPUS treatment vs control |

Abbreviation: ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists; CP/CPPS: chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome; ED: erectile dysfunction; ET: exercise therapy; FLIPUS: focused low-intensity pulsed ultrasound; GABA: γ-Aminobutyric Acid; IVRO: intraoral vertical ramus osteotomy; HADMSCs: human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells; HILT: high intensity laser therapy; KOA: Knee Osteoarthritis; LIPUS: low-intensity pulsed ultrasound; OA: osteoarthritis; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; PD: Parkinson disease; RCT: randomized control trial; RPT: routine physiotherapy; TENS: transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation; TMD: temporomandibular disorders; vs: versus.

The main mechanism of LIPUS in tissue injury: anti-inflammation and repair. LIPUS promotes the osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs and enhances angiogenesis to facilitate fracture healing. (B) LIPUS improves chronic prostatitis by regulating the balance of microbiota. (C) LIPUS reduces inflammation in chondrocytes and synovial cells, while promoting the formation of the extracellular matrix. (D) LIPUS promotes the increase of BDNF to protect the brain or peripheral nerve injury and reduce the infiltration of M1-like inflammatory cells; it alleviates ER stress to protect neurons. (E) LIPUS promotes the increase of BDNF to protect the brain or peripheral nerve injury and reduce the infiltration of M1-like inflammatory cells; it alleviates ER stress to protect neurons. (F) LIPUS reduces the production of inflammatory factors and fibroblasts to alleviate inflammation and fibrosis. (G) LIPUS alleviates degenerative human nucleus pulposus by promoting extracellular matrix formation and reducing inflammatory factors. (H) LIPUS alleviates renal injury-induced fibrosis by reducing TGF. (I) LIPUS promotes muscle injury repair by reducing M1 cells and increasing myotubes and myoblasts. Figure was drawn by BioRender.com. Abbreviation: BDNF: brain-derived neurotrophic factor; BMSC: bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell; HIF: hypoxia-inducible factor; HPDLC: human periodontal ligament cell; JNK: c-Jun N-terminal kinase; LIPUS: low intensity pulse ultrasound; NF-κB: nuclear factor-κB; TGF-β: transforming growth factor-β.

4.2 Chronic prostatitis

LIPUS has also shown promise in treating of chronic inflammation, such as chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS) [70]. In 2013, Li et al. evaluated the clinical efficacy and safety of transperineal ultrasound therapy for CP treatment. Analyzing the National Institutes of Health Chronic Prostatitis Symptom Index (NIH-CPSI) scores, routine prostate exams and prostate fluid expression in a randomized, double-blind, multicenter trial of 96 patients, results showed that the overall efficacy of 70.83% in the LIPUS group [71].

LIPUS is gaining attention as a novel physical therapy for refractory type IIIB prostatitis. It may exert therapeutic effects by altering the microbial community structure in prostatic fluid. In a study of 25 patients with type IIIB prostatitis, LIPUS treatment (10 minutes per session, every other day, 5 sessions per cycle, two cycles) reduced NIH-CPSI scores by 4 points or more. Song et al. found that LIPUS significantly affected the bacterial composition in prostatic fluid, reducing pathogens such as Veillonella, Methyloversatilis, and Ureaplasma. The proposed mechanism suggests the ultrasound energy disrupts bacterial cell structures, reducing their numbers and alleviating prostatitis symptoms. Additionally, changes in microbial diversity suggest that LIPUS may improve the inflammatory environment by restoring microbial balance [15].

4.3 Osteoarthritis

Zhang et al. [41] demonstrated that LIPUS enhances cartilage healing through the phosphorylation of FAK and Src family kinases (SFKs). The complex formation induces chondrogenic progenitor cells (CPCs) to migrate to the cartilage injury site, delaying or preventing post-traumatic osteoarthritis (PTOA) onset. Furthermore, LIPUS accelerated cartilage matrix synthesis to promote cartilage regeneration. Peng et al. [37] reported that LIPUS regulates extracellular matrix expression in early and late osteoarthritic cartilage through the integrin/FAK/MAPK pathway. While LIPUS significantly increased type II collagen expression in early osteoarthritic cartilage, it decreased matrix metalloproteinase-13 (MMP-13) levels. LIPUS regulates chondrocyte metabolism by stimulating the primary cilia, which activate TRPV4 channels and modulate intracellular Ca2+ levels. This suppresses endoplasmic reticulum stress, reduces chondrocyte apoptosis, and increases the expression of cartilage matrix components. Additionally, silencing IFT88, which affects primary cilia expression, disrupts LIPUS's protective effect on cartilage [72].

Furthermore, impaired autophagy leads to yes associated protein (YAP) accumulation, which binds with receptor-interacting protein kinase 1 (RIPK1), to activate the NF-κB pathway, exacerbating chondrocyte inflammation and extracellular matrix degradation. LIPUS inhibits this progression by restoring autophagy and reducing YAP-RIPK1 interaction. Optimal effects were achieved at 30 mW/cm² for 20 minutes, significantly suppressing inflammation and promoting matrix homeostasis [16]. Liao et al. [73] injected exosomes derived from bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell (BMSC) treated by LIPUS into the joint cavity. This treatment significantly attenuated cartilage destruction and promoted cartilage regeneration in OA. Furthermore, LIPUS irradiation of BMSC notably increased exosome production, enhancing their capacities.

LIPUS reduces infiltration and inflammation in the synovium. Osteoarticular synoviocytes may undergo modulation of apoptosis and survival through the integrin/FAK/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway. Sato et al. [74] found that LIPUS upregulates phosphorylated FAK in synovial cells, leading to decreased extracellular regulated protein kinases (ERK), c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), and p38 phosphorylation. Zachs et al. [75] investigated upregulated genes in T and B cells of arthritic mice treated with LIPUS-stimulated spleen. Changes in gene expression affecting cytoskeletal regulation influenced lymphocyte polarization and migration, reducing synovial infiltration. In addition, increased vagal signaling led to the aggregation of B cells in the splenic marginal zone. Genes encoding transcriptional regulators such as c-Jun and JunB were upregulated in T and B cells, potentially influencing inflammatory pathways. To address inflammation-induced fibrosis, Zhou et al. [24] observed that LIPUS alleviated immobilization-induced knee joint capsule fibrosis by inhibiting reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and activation of the TGF-β1/Smad signaling pathway.

LIPUS stimulation of rat mandibular chondrocytes in hypoxic conditions increased HIF-1α expression while decreasing HIF-2α [48], alleviating hypoxia-induced chondrocyte damage. Nagao et al. [76] demonstrated that LIPUS mechanical stress on angiotensin II receptor type 1 (AT1) activates phospholipase C-β (PLCβ). This mediates anti-inflammatory effects in LPS-induced osteoblasts by inhibiting NF-κB activation and decreasing IL-1α production. Moreover, the combination of LIPUS (1.5 MHz, 80 mW/cm2) and Fe3+, significantly accelerates the proliferation and differentiation of osteoblasts compared to single-factor treatments [72]. In osteoarthritis repair, LIPUS improves the trabecular microstructure and histological features of subchondral bone by inhibiting osteoclast activity and the TGF-β1/Smad3 signaling pathway in a temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis (TMJOA) rabbit model [14].

4.4 Brain damage and dysfunction

LIPUS exposure increased BDNF expression in astrocytes in both in vitro and in vivo rat models, enhancing BDNF production through TrkB/PI3K/Akt, TrkB/phospholipase C(PLC)-γ/Ca2+, and calcium/calmodulin stimulated protein kinase (CaMK) signaling pathways [45]. BDNF/TrkB signaling can further boost BDNF induction via cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) through PI3K/Akt or ERK signaling [77]. Su et al. [78] reported that LIPUS therapy after traumatic brain injury (TBI) promoted BDNF production through the TrkB/Akt/CREB signaling pathway. This increased vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and reduced cleaved caspase-3 levels to prevent apoptosis. Wang et al. [79] applied LIPUS on TBI (800 kHz, 3 W/cm², 10 minutes daily), finding it promotes hippocampal neurogenesis, increases newborn neuron counts, and enhances phosphatidylcholine levels, thereby improving neural activity and cognitive function. Mechanisms may involve metabolic regulation and gene expression related to neurogenesis.

LIPUS inhibited the inflammatory response in activated microglia by modulating the signal transducer and activa tor of transcription 1 (STAT1)/STAT6 (attenuating STAT1 phosphorylation and promoting STAT6 phosphorylation) and peroxisome proliferator activated receptor γ (PPARγ) signaling pathways [80]. This reduces M1 markers (cytotoxic nitric oxide) and promotes M2 markers (L-arginine), shifting the phenotype to favor reduced cytotoxicity. LIPUS boosted M2a and M2c markers (CD206 and TLR8) but not the M2b marker CCL1. Unlike many drugs, LIPUS stands out due to its ability to penetrate the blood-brain barrier [80]. Li et al. [81] focused on LIPUS effects on cortical microelectrode implantation (1.13 MHz, 300 mW/cm²). LIPUS significantly accelerates the migration of microglia in the early post-implantation, promoting a branched morphology, and enhances monitoring activity. In later stages, it reduces microglial coverage around the electrode and astrocytic scar formation, while improving neuronal recording performance. Potential mechanisms involve ATP release, metabolic regulation. In heart failure rats, head stimulation with LIPUS alleviated neuroinflammation and sympathetic overactivation by inhibiting the P2X7/NLRP3 pathway in microglia, preventing ventricular arrhythmias [82]. LIPUS stimulation (100 mW/cm2) increases hippocampal neuronal cytosolic Ca2+ concentration within 5 minutes by enhancing Ca2+ influx through L-type calcium channels (LTCCs), without effecting stored Ca2+. It also promotes CREB phosphorylation and nuclear translocation, dependent on LTCC-induced Ca2+ influx [83]. Truong et al. [84] showed that LIPUS reduces endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress in motor neuron cells by lowering toxic protein levels. It protects cells from oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction by reducing ROS and increasing mitochondrial membrane potential. LIPUS activates calcium signaling, AKT, and calcium-dependent transcription factors, enhancing cell survival (1.15 MHz, 356.78 mW/cm², 8 minutes). A protocol was established to investigate wearable LIPUS for Parkinson's Disease (PD) motor symptoms [85]. This was a single-center, prospective, double-blind, randomized controlled trial, aiming to recruit 48 PD patients. The LIPUS group receives treatment (600 kHz, 1.0 W/cm², 50% duty cycle) for 30 minutes daily over 4 months, compared to a sham group.

4.5 Peripheral nerves injury

Xia et al. [19] reported that LIPUS significantly upregulated phosphorylated FAK and activated ERK1/2 to promote proliferation and neural differentiation of iPSCs-NCSCs, aiding peripheral nerves regeneration. Furthermore, LIPUS activated Schwann cells (SCs) through the TrkB/Akt/CREB axis in peripheral nerves. This treatment enhanced SCs proliferation, migration, and nerve growth factor expression, effectively treating erectile dysfunction (ED) resulting from bilateral cavernous nerve injury [13].

Exosomes from LIPUS-stimulated SCs (LIPUS-SCs-Exo) showed the surprising capacity to enhance axonal growth of pelvic ganglion (MPG) neurons/cavernous nerves and MPG neurons. In rats with bilateral cavernous nerve crush injury (BCNI) induced ED, LIPUS-SCs-Exo promoted injured CN regeneration and SCs proliferation. High-throughput sequencing showed that LIPUS stimulation regulates the genes of MPG neurons by altering SCs-Exo derived miRNAs, thereby activating the PI3K/Akt/Forkhead Box O (FoxO) signaling pathway, promoting nerve regeneration and restoring ED [86].

4.6 Periodontal tissue damage

During orthodontic treatment, mechanical forces trigger alveolar bone changes. LIPUS plays a crucial regulatory role in this process. LIPUS plays a crucial regulatory role in this process. Hu et al. [25] found that LIPUS promoted endothelial differentiation and angiogenesis of periodontal ligament stem cells (PDLSCs) through Piezo1 activation, promoting tissue regeneration. LIPUS exposure might induce osteogenic differentiation of PDLSCs through the BMP-Smad signaling pathway [87]. This irradiation significantly increased Smad1/5/8 phosphorylation, leading to its subsequent translocation from the cytoplasm to the nucleus. Zhong et al. [88] demonstrated that LIPUS mitigated alveolar bone resorption under pressure and enhanced osteogenic capacity by downregulating Piezo1 expression.

LIPUS regulated osteoblast-osteoclast crosstalk for orthodontic alveolar bone remodeling. In 2023, Zhou et al. [33] reported that in a BMSC and bone marrow mononuclear cell (BMM) co-culture, the EphrinB2/EphB4 dimer exerted mechanotransduction functions in response to LIPUS. It regulated YAP nuclear translocation through F-actin rearrangement, facilitating osteogenesis and alveolar bone remodeling.

4.7 Cardiovascular disease

Cao et al. [10] revealed that hypoxia during MI/R triggered nuclear HIF-1α binding, upregulates NADPH oxidase 4 (Nox4), and increased ROS, leading to inflammation. LIPUS (0.5 W/cm²) attenuated this response by decreasing HIF-1α expression and suppressing ASK1 and JNK pathways. Sun et al. [89] used LIPUS (1 MHz, 0.25 W/cm2 and 20% duty ratio) to treat the MI/R mouse model. The LIPUS group received treatment for 20 min three times a day on days 0-7, and twice a week during weeks 2-4, and a duty cycle of 20%. LIPUS activates the RhoA/Myosin II pathway to promote cytoskeletal rearrangement and migrasome formation. It also activates YAP nuclear translocation, which in turn transcriptionally activates KIF5B and Drp1 to facilitate mitocytosis.

Liu et al. [90] observed that LIPUS significantly increased Treg cell infiltration in myocarditis hearts and decreased the migration of pro-inflammatory CCR2+ macrophages. LIPUS modulated inflammatory cytokines associated with Th17 cells, Treg cells, and macrophages. Besides alleviating inflammation, LIPUS can mitigate hypoxia-induced cardiac fibrosis. Zhao et al. [17] demonstrated that LIPUS partially mitigated hypoxia-induced cardiac fibroblast phenotypic changes through the TWIK-related arachidonic acid-activated K+ channel (TRAAK)-mediated HIF-1α/DNA methyltransferase3α (DNMT3α) pathway. It reduced fibrotic markers like α-SMA, TGF-β, and collagen I. However, intensity matters: while 0.5 W/cm² provided protection, 2.5 W/cm² worsened cardiomyocyte injury [10].

LIPUS can transmit signals integrins [19]. Bernal et al. [9] found that in cardiac mesoangioblasts (CMA), LIPUS triggers a conformational change in β1-integrin to its active form, promoting BMP receptor activation. Shindo et al. [91] evaluated the efficacy and safety of LIPUS in 64 patients with refractory angina. During LIPUS treatment, patients were positioned in the left lateral decubitus, with the probe placed on the anterior chest wall. Treatment was applied at a frequency of 1.875 MHz, intensity of 0.25 MPa, and 32 cycles. Each section was irradiated for 20 minutes, with a 5-minute interval between sections. Treatments were administered every other day, for a total of 3 days. While both LIPUS and placebo groups showed reduced nitroglycerin usage, there was no significant difference between them. However, the all-cause mortality rate was lower in the LIPUS group (3.1%) vs. placebo (13.8%), though not statistically significant.

In diabetic wound healing, LIPUS enhances the therapeutic effects of adipose-derived stem cell exosomes (ADSC-Exos). In vivo, LIPUS increased exosome uptake, prolonged their retention at the wound site, and promoted angiogenesis and wound healing. In vitro, LIPUS enhanced exosome uptake by 10.93 times and significantly promoted human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) proliferation, migration, and tube formation [92]. A study on 25 patients with Buerger's disease showed that LIPUS (2.0 MHz, 30 mW/cm², 20 minutes daily, 20% duty cycle) significantly reduced resting pain and improved skin perfusion pressure over 24 weeks [93].

4.8 Degenerative human nucleus pulposus

Zhang et al. [42] discovered that LIPUS promotes extracellular matrix (ECM) synthesis in degenerative human nucleus pulposus (NP) cells using the FAK/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt pathway. Yi et al. [56] reported that in LPS-induced NP cells, LIPUS inhibited the NF-κB pathway by suppressing p-P65 protein expression and P65 nuclear translocation, blocking inflammation and catabolism.

4.9 Kidney injury

Inoue et al. demonstrated that ultrasound therapy before ischemia-reperfusion injury preserved kidney structure and function through CAP activation [94]. Similarly, in an adriamycin-induced chronic renal injury model, LIPUS ameliorated injury by blocking TGF-β1/Smad signaling and the Nrf2/keap1/HO-1 pathway to reduce fibrosis and inflammation [18].

4.10 Muscle and tendon injury

Evaldo et al. [20] used LIPUS to treat cryoinjury in rat tibialis anterior muscle. LIPUS decreased neutrophils and inflammatory macrophages (M1) in the first 24 hours. By day two, reparative macrophages (M2) increased, but by day three, M2 levels were lower than in untreated muscles. This suggests LIPUS promotes the early transition of inflammatory macrophages and regulates reparative macrophages to attenuate fibrosis. Qin et al. [58] demonstrated that the WNT/FZD5/β-catenin axis was key for LIPUS-promoted M2 polarization. Macrophage depletion studies confirmed their integral role in LIPUS-mediated effects [95].

Duan et al. [96] highlighted the beneficial effects of LIPUS treatment on skeletal muscle regeneration, primarily through the modulation of satellite cell/myoblast mitochondrial metabolism. LIPUS (1 MHz, 250 mW/cm², 20% duty cycle) accelerated recovery, increased satellite cell counts, and reduced fibrosis via the AMP-activated protein kinase pathway. In rotator cuff repair, Wu et al. [21] investigated exosomes from BMSCs pretreated with LIPUS. These exosomes promoted fibrous cartilage regeneration at the bone-tendon interface, reduced fat infiltration, and regulated specific miRNAs (e.g., miR-140).

5. Discussion and conclusion

LIPUS has emerged as a highly promising non-invasive physical therapy with the potential to address a diverse range of inflammatory diseases and tissue repair needs. It has demonstrated significant capabilities in anti-inflammation and promoting tissue repair across multiple conditions, including bone fractures [69], chronic prostatitis [26, 70], osteoarthritis [48, 75], brain damage [78], peripheral nerve injuries [13, 19], periodontal tissue damage [87], cardiovascular diseases [9, 10], kidney injuries, muscle and tendon injuries [96], and degenerative human nucleus pulposus [56].

In the realm of basic research, numerous in vivo and in vitro studies have elucidated several key molecular mechanisms underlying LIPUS's effects. These involve the modulation of signaling pathways such as FAK, BDNF, TGF-β, HIF, CAP, NF-κB, and the regulation of macrophage polarization and extracellular vesicles. These pathways are not isolated; rather, they are interconnected, forming a complex bioregulatory network. For instance, LIPUS can stimulate BDNF expression in astrocytes directly [78] or via NF-κB activation [45]. The NF-κB signaling pathway can be targeted and inhibited by LIPUS-EVs [61] or directly irradiation [56]. Compared to targeted drugs, such as those that specifically inhibit TLR8 or target the MAPK/NF-κB pathway, LIPUS, as a physical therapy, offers a safe, multi-functional technology particularly suited for localized inflammation and tissue repair. Molecularly targeted drugs, on the other hand, provide powerful precision capabilities, making them ideal for systemic or intractable diseases [97, 98].

As we also mentioned, LIPUS regulates macrophage migration activation, the TGF-β/SMAD signaling pathway and HIF-related molecules [17, 24, 90]. Recent findings suggest that Ly6Chi macrophages migrate to the hypoxic zone and secrete oncostatin-M, in a HIF-1α-dependent manner, inhibiting TGF-β/SMAD signaling [99]. This indicates a potential regulatory network for LIPUS in preventing cardiac fibrosis.

Different combinations of intracellular signaling pathways may produce varying effects depending on cell state, LIPUS intensity, and duration. For example, LIPUS effectiveness in osteoarthritis varies; while it improves cartilage function in mild cases, its effect may be limited in severe cases [37]. While efficacy is well-demonstrated in preclinical studies, clinical data remain limited. A systematic review of bone traction osteogenesis found that LIPUS did not significantly shorten treatment duration or affect complications [100]. Therefore, high-quality clinical trials are needed to validate translational potential. Standardized parameters for LIPUS use must be established, and adverse reactions monitored.

Although numerous signaling pathways (e.g., FAK, BDNF, TGF-β, NF-κB) have been identified, the current understanding of LIPUS efficacy should not be viewed as a collection of isolated events. Instead, LIPUS likely functions by orchestrating a “unified biological picture” through the spatiotemporal coupling of mechanotransduction and inflammatory signaling. The mechanical signals initiated by LIPUS are not merely physical perturbations; they act as upstream switches that modulate downstream chemical signaling networks. For instance, a critical crosstalk likely exists between mechanosensitive ion channels (e.g., Piezo1) and classical inflammatory pathways (e.g., NF-κB). Mechanical deformation of the cell membrane by LIPUS opens calcium channels, and the resulting Ca2+ influx may act as a temporal regulator-brief, controlled influxes can activate reparative pathways like ERK1/2 and BDNF, while potentially inhibiting the sustained inflammatory activation of NF-κB. This suggests that LIPUS acts as an “intelligent” modulator, shifting the cellular state from a pro-inflammatory phenotype to a reparative one by integrating physical cues with biochemical responses. Future research must decipher this spatiotemporal coupling: how the immediate physical effect on the membrane translates into delayed, long-term gene expression changes that resolve inflammation.

A critical analysis of the dose-effect relationship remains a significant gap in current literature (Table 3). The biological outcome of LIPUS is strictly parameter-dependent, where “more” is not necessarily “better”. Variations in frequency, intensity, and duty cycle can lead to divergent, sometimes opposite, biological results. Tissue type and parameters influence context-dependent responses. For example, in bone repair, LIPUS can promote osteogenesis through pathways related to integrins and calcium oscillations [67]. In osteoarthritis, it can regulate chondrocyte metabolism and extracellular matrix synthesis [16, 37], and in brain disorders, it can enhance neurogenesis and modulate microglia activation [80]. While lower intensities (e.g., 30-100 mW/cm²) typically promote anti-inflammatory M2 macrophage polarization and tissue regeneration [30, 58], higher intensities (e.g., >2.5 W/cm²) can induce thermal damage, exacerbate oxidative stress, or trigger cardiomyocyte injury [10]. Frequency also dictates the depth of penetration and the scale of interaction; lower frequencies (kHz range) may generate different acoustic streaming patterns compared to MHz frequencies, affecting how mechanoreceptors are triggered. Consequently, there is no “one-size-fits-all” protocol. We propose that future optimization should move towards “disease-specific parameter windows”. For superficial, acute inflammation (e.g., wound healing), lower intensities with higher frequencies might suffice to stimulate angiogenesis without aggravating inflammation. Conversely, deep-tissue chronic fibrosis might require distinct modulation patterns to penetrate effectively while inhibiting TGF-β signaling. Establishing a standardized matrix of parameters correlated with specific biological endpoints (e.g., ROS levels, cytokine profiles) is essential for clinical reproducibility.

Relationship Between Parameters and Specific Effects

| Target Disease/Effect | LIPUS Parameters (Intensity, Frequency, Temporal Mode) | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Bone Repair | 30 mW/cm², 1.5 MHz, 20 min/day | [64, 66, 68, 109] |

| Osteoarthritis | 30-45 mW/cm², 1-1.5 MHz, 20 min/day | [16, 37, 72, 74, 107] |

| Nerve Repair | 80-300 mW/cm², 1 MHz, 10-20 min/day | [13, 45, 78, 80] |

| Cardiovascular Disease | 77.2-500 mW/cm², 0.5-1 MHz, 20 min/day | [10, 17] |

| Chronic Inflammation (e.g., Prostatitis) | Parameters not explicitly detailed, but clinical efficacy shown | [15, 26] |

| Extracellular Vesicle Regulation | 300 mW/cm², 1-1.5 MHz, 12-15 min | [61, 62] |

| Muscle Injury | 40-250 mW/cm², 1 MHz, 3-20 min/day | [58, 95, 96] |

| Intervertebral disc degeneration | 30 mW/cm², 1.5 MHz, 20 min/day | [42, 56] |

6. Perspective

Future research on LIPUS should focus on several key areas. Studies must transcend tissue-level observations by leveraging single-cell multi-omics, spatial transcriptomics, and epigenomics. This will enable the precise identification of cell subpopulations regulated by LIPUS, revealing their roles in reprogramming cell fate and intercellular communication. Constructing pseudo-temporal trajectories will help map the complete pathway of LIPUS-promoted anti-inflammation and repair. First, it is crucial to investigate the intricate relationships and synergistic effects among signaling pathways. Understanding these interactions could provide deeper insights into the mechanism of action. Second, clinical translation can be advanced by integrating LIPUS with advanced biomaterials. Developing LIPUS-responsive smart drug delivery systems enables the synergistic release of physical stimulation and chemical drugs. Combining LIPUS with tissue engineering scaffolds can construct biomimetic microenvironments to guide cellular behavior. Efforts must be made to establish standardized parameters (intensity, frequency, duration) for specific diseases. Standardization will enhance reproducibility and facilitate bench-to-bedside translation. Finally, comprehensive clinical trials with larger sample sizes and long-term follow-up are essential to accurately assess safety and efficacy. Comparative studies will determine the most effective treatment strategies.

Abbreviations

ADSC-Exos: adipose-derived stem cell exosomes; AT1: angiotensin type 1 receptor; ASK1: apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1; AQP5: aquaporin Protein-5; BCNI: bilateral cavernous nerve crush injury; BDNF: brain-derived neurotrophic factor; BMSCs: bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells; BMDCs: bone marrow dendritic cells; SC: schwann cell; BMMs: bone marrow mononuclear cells; CAP: cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway; CaMK: calcium/calmodulin stimulated protein kinase; CREB: cyclic-AMP response binding protein; CP/CPPS: chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome; CPC: chondrogenic progenitor cell; SFKs: Src family kinases; CTGF: connective tissue growth factor; CKD: chronic kidney disease; CMAs: Cardiac mesoangioblasts; DNMT3a: DNA methyltransferase 3 α; ED: erectile dysfunction; ER: endoplasmic reticulum; ERK1/2: extracellular regulated protein kinases 1/2; EVs: extracellular vesicles; FAK: focal adhesion kinase; FBXL2: F-box and leucine rich repeat protein 2 gene; FoxO: Forkhead Box O; HPDLC: human periodontal ligament cell; iPSCs-NCSCs: induced pluripotent stem cells-derived neural crest stem cells; HIF: hypoxia-inducible factor; HUVECs: human umbilical vein endothelial cells; IVD: intervertebral disk; JNK: c-Jun N-terminal kinase; LIPUS: low intensity pulse ultrasound; MAPK: mitogen-activated protein kinase; LTCCs: L-type calcium channels; MI/R: myocardial ischemia/reperfusion; NF-κB: nuclear factor-κB; OA: osteoarthritis; NP: nucleus pulposus; Nrf2/keap1/HO-1: nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2/the Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1/heme oxygenase 1; NED: neurogenic ED; PTOA: posttraumatic osteoarthritis; PI3K: phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; PLCβ: phospholipase C β; PPARγ: peroxisome proliferator activated receptor γ; PDLSCs: periodontal ligament stem cells; RA: rheumatoid arthritis; RIPK1: receptor-interacting protein kinase 1; STAT1: signal transducer and activa tor of transcription 1; SCs: Schwann cells; TA: tibialis anterior; TrkB: tyrosine Kinase receptor B; TBI: traumatic brain injury; TGF-β: transforming growth factor-β; TMJOA: temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis; TLR4: toll like receptor 4; TAC: transverse aortic constriction; TRAF6: TNF receptor associated factor 6; TMJ: temporomandibular joint; TNF-α: tumor necrosis factor α; YAP: yes associated protein.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82170633).

Author contributions

Gao-cheng Wang: Writing-original draft, Resources, Methodology, Investigation. Jian-ping Zhao: Writing-review and editing, Supervision, Methodology, Investigation. Jia-xuan Li: Resources, Investigation. Zhan-guo Zhang: Resources, Supervision, Investigation. Wan-guang Zhang: Resources, Investigation. Qian Chen: Resources, Investigation. Jing-jing Wang: Writing-review and editing, Supervision, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization.

Competing interests

The authors have declared that no competing interest exists.

References

1. Zhu X, Yue M, Zhang X, Han Y, Xia R, Zhang Q. et al. Global Disease Burden of Immune-Mediated Inflammatory Diseases (IMIDs), 1990-2021. Med Research. 2025;1:285-96

2. Furman D, Campisi J, Verdin E, Carrera-Bastos P, Targ S, Franceschi C. et al. Chronic inflammation in the etiology of disease across the life span. Nat Med. 2019;25:1822-32

3. Weiskirchen R, Weiskirchen S, Tacke F. Organ and tissue fibrosis: Molecular signals, cellular mechanisms and translational implications. Mol Aspects Med. 2019;65:2-15

4. Cai Z, Wang S, Li J. Treatment of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Comprehensive Review. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:765474

5. Yao Q, Wu X, Tao C, Gong W, Chen M, Qu M. et al. Osteoarthritis: pathogenic signaling pathways and therapeutic targets. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8:56

6. Jiang X, Savchenko O, Li Y, Qi S, Yang T, Zhang W. et al. A Review of Low-Intensity Pulsed Ultrasound for Therapeutic Applications. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2019;66:2704-18

7. Khanna A, Nelmes RT, Gougoulias N, Maffulli N, Gray J. The effects of LIPUS on soft-tissue healing: a review of literature. Br Med Bull. 2009;89:169-82

8. Bashardoust Tajali S, Houghton P, MacDermid JC, Grewal R. Effects of low-intensity pulsed ultrasound therapy on fracture healing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;91:349-67

9. Bernal A, Perez LM, De Lucas B, Martin NS, Kadow-Romacker A, Plaza G. et al. Low-Intensity Pulsed Ultrasound Improves the Functional Properties of Cardiac Mesoangioblasts. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2015;11:852-65

10. Cao Q, Liu L, Hu Y, Cao S, Tan T, Huang X. et al. Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound of different intensities differently affects myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury by modulating cardiac oxidative stress and inflammatory reaction. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1248056

11. Li X, Zhong Y, Zhang L, Xie M. Recent advances in the molecular mechanisms of low-intensity pulsed ultrasound against inflammation. J Mol Med (Berl). 2023;101:361-74

12. Chen J, Jiang J, Wang W, Qin J, Chen J, Chen W. et al. Low intensity pulsed ultrasound promotes the migration of bone marrow- derived mesenchymal stem cells via activating FAK-ERK1/2 signalling pathway. Artif Cells Nanomed Biotechnol. 2019;47:3603-13

13. Li Z, Ye K, Yin Y, Zhou J, Li D, Gan Y. et al. Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound ameliorates erectile dysfunction induced by bilateral cavernous nerve injury through enhancing Schwann cell-mediated cavernous nerve regeneration. Andrology. 2023;11:1188-202

14. Yi X, Wu L, Liu J, Qin YX, Li B, Zhou Q. Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound protects subchondral bone in rabbit temporomandibular joint osteoarthritis by suppressing TGF-beta1/Smad3 pathway. J Orthop Res. 2020;38:2505-12

15. Song WJ, Huang JW, Liu Y, Wang J, Ding W, Chen BL. et al. Effects of low-intensity pulsed ultrasound on the microorganisms of expressed prostatic secretion in patients with IIIB prostatitis. Sci Rep. 2024;14:15368

16. Pan C, Lu F, Hao X, Deng X, Liu J, Sun K. et al. Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound delays the progression of osteoarthritis by regulating the YAP-RIPK1-NF-kappaB axis and influencing autophagy. J Transl Med. 2024;22:286

17. Zhao K, Weng L, Xu T, Yang C, Zhang J, Ni G. et al. Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound prevents prolonged hypoxia-induced cardiac fibrosis through HIF-1alpha/DNMT3a pathway via a TRAAK-dependent manner. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2021;48:1500-14

18. Ouyang ZQ, Shao LS, Wang WP, Ke TF, Chen D, Zheng GR. et al. Low intensity pulsed ultrasound ameliorates Adriamycin-induced chronic renal injury by inhibiting ferroptosis. Redox Rep. 2023;28:2251237

19. Xia B, Chen G, Zou Y, Yang L, Pan J, Lv Y. Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound combination with induced pluripotent stem cells-derived neural crest stem cells and growth differentiation factor 5 promotes sciatic nerve regeneration and functional recovery. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2019;13:625-36

20. da Silva Junior EM, Mesquita-Ferrari RA, Franca CM, Andreo L, Bussadori SK, Fernandes KPS. Modulating effect of low intensity pulsed ultrasound on the phenotype of inflammatory cells. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;96:1147-53

21. Wu B, Zhang T, Chen H, Shi X, Guan C, Hu J. et al. Exosomes derived from bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell preconditioned by low-intensity pulsed ultrasound stimulation promote bone-tendon interface fibrocartilage regeneration and ameliorate rotator cuff fatty infiltration. J Orthop Translat. 2024;48:89-106

22. Miller DL, Smith NB, Bailey MR, Czarnota GJ, Hynynen K, Makin IR. et al. Overview of therapeutic ultrasound applications and safety considerations. J Ultrasound Med. 2012;31:623-34

23. Baker KG, Robertson VJ, Duck FA. A review of therapeutic ultrasound: biophysical effects. Phys Ther. 2001;81:1351-8

24. Zhou T, Zhou CX, Zhang QB, Wang F, Zhou Y. LIPUS Alleviates Knee Joint Capsule Fibrosis in Rabbits by Regulating SOD/ROS Dynamics and Inhibiting the TGF-beta1/Smad Signaling Pathway. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2023;49:2510-8

25. Hu R, Yang ZY, Li YH, Zhou Z. LIPUS Promotes Endothelial Differentiation and Angiogenesis of Periodontal Ligament Stem Cells by Activating Piezo1. Int J Stem Cells. 2022;15:372-83

26. Lin G, Reed-Maldonado AB, Lin M, Xin Z, Lue TF. Effects and Mechanisms of Low-Intensity Pulsed Ultrasound for Chronic Prostatitis and Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome. Int J Mol Sci. 2016 17

27. Tanaka E, Kuroda S, Horiuchi S, Tabata A, El-Bialy T. Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound in dentofacial tissue engineering. Ann Biomed Eng. 2015;43:871-86

28. Warden SJ. A new direction for ultrasound therapy in sports medicine. Sports Med. 2003;33:95-107

29. Ahmadi F, McLoughlin IV, Chauhan S, ter-Haar G. Bio-effects and safety of low-intensity, low-frequency ultrasonic exposure. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2012;108:119-38

30. Watson T. Ultrasound in contemporary physiotherapy practice. Ultrasonics. 2008;48:321-9

31. Wu S, Xu X, Sun J, Zhang Y, Shi J, Xu T. Low-Intensity Pulsed Ultrasound Accelerates Traumatic Vertebral Fracture Healing by Coupling Proliferation of Type H Microvessels. J Ultrasound Med. 2018;37:1733-42

32. Li W, Li X, Kong Z, Chen B, Zhou H, Jiang Y. et al. Efficacy of low-intensity pulsed ultrasound in the treatment of COVID-19 pneumonia. Ultraschall Med. 2023;44:e274-e83

33. Zhou J, Zhu Y, Ai D, Zhou M, Li H, Fu Y. et al. Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound regulates osteoblast-osteoclast crosstalk via EphrinB2/EphB4 signaling for orthodontic alveolar bone remodeling. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2023;11:1192720

34. Pei F, Liu J, Zhang L, Pan X, Huang W, Cen X. et al. The functions of mechanosensitive ion channels in tooth and bone tissues. Cell Signal. 2021;78:109877

35. Zhang G, Li X, Wu L, Qin YX. Piezo1 channel activation in response to mechanobiological acoustic radiation force in osteoblastic cells. Bone Res. 2021;9:16

36. Subramanian A, Budhiraja G, Sahu N. Chondrocyte primary cilium is mechanosensitive and responds to low-intensity-ultrasound by altering its length and orientation. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2017;91:60-4

37. Xia P, Shen S, Lin Q, Cheng K, Ren S, Gao M. et al. Low-Intensity Pulsed Ultrasound Treatment at an Early Osteoarthritis Stage Protects Rabbit Cartilage From Damage via the Integrin/Focal Adhesion Kinase/Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Signaling Pathway. J Ultrasound Med. 2015;34:1991-9

38. Tapial Martinez P, Lopez Navajas P, Lietha D. FAK Structure and Regulation by Membrane Interactions and Force in Focal Adhesions. Biomolecules. 2020 10

39. Zhao X, Guan JL. Focal adhesion kinase and its signaling pathways in cell migration and angiogenesis. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2011;63:610-5

40. Atherton P, Lausecker F, Harrison A, Ballestrem C. Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound promotes cell motility through vinculin-controlled Rac1 GTPase activity. J Cell Sci. 2017;130:2277-91

41. Jang KW, Ding L, Seol D, Lim TH, Buckwalter JA, Martin JA. Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound promotes chondrogenic progenitor cell migration via focal adhesion kinase pathway. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2014;40:1177-86

42. Zhang X, Hu Z, Hao J, Shen J. Low Intensity Pulsed Ultrasound Promotes the Extracellular Matrix Synthesis of Degenerative Human Nucleus Pulposus Cells Through FAK/PI3K/Akt Pathway. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2016;41:E248-54

43. Numakawa T, Kajihara R. Involvement of brain-derived neurotrophic factor signaling in the pathogenesis of stress-related brain diseases. Front Mol Neurosci. 2023;16:1247422

44. Bjorkholm C, Monteggia LM. BDNF - a key transducer of antidepressant effects. Neuropharmacology. 2016;102:72-9

45. Liu SH, Lai YL, Chen BL, Yang FY. Ultrasound Enhances the Expression of Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor in Astrocyte Through Activation of TrkB-Akt and Calcium-CaMK Signaling Pathways. Cereb Cortex. 2017;27:3152-60

46. Massague J, Sheppard D. TGF-beta signaling in health and disease. Cell. 2023;186:4007-37

47. Sato T, Takeda N. The roles of HIF-1alpha signaling in cardiovascular diseases. J Cardiol. 2023;81:202-8

48. Yang T, Liang C, Chen L, Li J, Geng W. Low-Intensity Pulsed Ultrasound Alleviates Hypoxia-Induced Chondrocyte Damage in Temporomandibular Disorders by Modulating the Hypoxia-Inducible Factor Pathway. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:689

49. Klunko NS, Achmad H, Abdullah TM, Mohammed S, Saha I, Salim KS. et al. The Anti-hypoxia Potentials of Trans-sodium Crocetinate in Hypoxiarelated Diseases: A Review. Curr Radiopharm. 2024;17:30-7

50. Kelly MJ, Breathnach C, Tracey KJ, Donnelly SC. Manipulation of the inflammatory reflex as a therapeutic strategy. Cell Rep Med. 2022;3:100696

51. Nunes NS, Chandran P, Sundby M, Visioli F, da Costa Goncalves F, Burks SR. et al. Therapeutic ultrasound attenuates DSS-induced colitis through the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway. EBioMedicine. 2019;45:495-510

52. Pasparakis M, Luedde T, Schmidt-Supprian M. Dissection of the NF-kappaB signalling cascade in transgenic and knockout mice. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:861-72

53. Sato M, Kuroda S, Mansjur KQ, Khaliunaa G, Nagata K, Horiuchi S. et al. Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound rescues insufficient salivary secretion in autoimmune sialadenitis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2015;17:278

54. Vereecke L, Beyaert R, van Loo G. The ubiquitin-editing enzyme A20 (TNFAIP3) is a central regulator of immunopathology. Trends Immunol. 2009;30:383-91

55. Zhao X, Zhao G, Shi Z, Zhou C, Chen Y, Hu B. et al. Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound (LIPUS) prevents periprosthetic inflammatory loosening through FBXL2-TRAF6 ubiquitination pathway. Sci Rep. 2017;7:45779

56. Yi W, Chen Q, Liu C, Li K, Tao B, Tian G. et al. LIPUS inhibits inflammation and catabolism through the NF-kappaB pathway in human degenerative nucleus pulposus cells. J Orthop Surg Res. 2021;16:619

57. Kadomoto S, Izumi K, Mizokami A. Macrophage Polarity and Disease Control. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 23

58. Qin H, Luo Z, Sun Y, He Z, Qi B, Chen Y. et al. Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound promotes skeletal muscle regeneration via modulating the inflammatory immune microenvironment. Int J Biol Sci. 2023;19:1123-45

59. Zhang X, Hu B, Sun J, Li J, Liu S, Song J. Inhibitory Effect of Low-Intensity Pulsed Ultrasound on the Expression of Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Inflammatory Factors in U937 Cells. J Ultrasound Med. 2017;36:2419-29

60. Chen Y, Zhang H, Hu X, Cai W, Jiang L, Wang Y. et al. Extracellular Vesicles: Therapeutic Potential in Central Nervous System Trauma by Regulating Cell Death. Mol Neurobiol. 2023;60:6789-813