Impact Factor

ISSN: 1449-1907

Int J Med Sci 2023; 20(5):566-571. doi:10.7150/ijms.82054 This issue Cite

Research Paper

Peripheral Parenteral Nutrition Solutions and Bed Bath Towels as Risk Factors for Nosocomial Peripheral Venous Catheter-related Bloodstream Infection by Bacillus cereus

1. Clinical Pharmacology, Graduate School of Medicine, Yamaguchi University, Japan.

2. Pharmacy Department, Yamaguchi University Hospital, Japan

3. Department of Pharmacy, Hofu Institute of Gastroenterology, Japan

4. Clinical Laboratory, Yamaguchi University Hospital, Japan

5. Department of Infection Prevention and Control, Tokyo Medical University Hospital, Japan

6. Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Sanyo-Onoda City University, Japan

Received 2022-12-21; Accepted 2023-2-28; Published 2023-3-5

Abstract

In Japan, China, and Singapore, several studies have reported increased incidences of peripheral venous catheter-related bloodstream infection by Bacillus cereus during the summer. Therefore, we hypothesized that bed bathing with a B. cereus-contaminated “clean” towels increases B. cereus contact with the catheter and increases the odds of contaminating the peripheral parenteral nutrition (PPN). We found that 1) professionally laundered “clean” towels used in hospitals have B. cereus (3.3×104 colony forming units (CFUs) / 25cm2), 2) B. cereus is transferable onto the forearms of volunteers by wiping with the towels (n=9), and 3) B. cereus remain detectable (80∼660 CFUs /50cm2) on the forearms of volunteers even with subsequent efforts of disinfection using alcohol wipes. We further confirmed that B. cereus grow robustly (102 CFUs /mL to more than 106 CFUs /mL) within 24hours at 30°C in PPN. Altogether we find that bed bathing with a towel contaminated with B. cereus leads to spore attachments to the skin, and that B. cereus can proliferate at an accelerated rate at 30°C compared to 20°C in PPN. We therefore highly recommend ensuring the use of sterile bed bath towels prior to PPN administration with catheter in patients requiring bed bathing.

Keywords: venous catheter -related bloodstream infection, Bacillus cereus, peripheral parenteral nutrition, microbial growth

Introduction

Bacillus cereus is a type of spore-producing bacteria that is often detected in air, soil, dust, water, and food [1]. Furthermore, this type of bacteria may cause relatively mild food poisoning. In addition, several studies reported that the use of bed bath towels or sheets contaminated with B. cereus induced peripheral venous catheter-related bloodstream infection (PVC-BSI) [2-5]. On the other hand, when B. cereus is detected in sterile samples of the human body, the spores are extensively distributed in a hospital environment; therefore, the situation is often regarded as contamination. However, an increasing number of studies suggested that B. cereus causes serious septicemia (bacteremia) [6-21]. In addition, the administration of peripheral parenteral nutrition containing glucose, amino acids, and electrolytes (PPN) [22-25] and the summer season [26-28] have been indicated as risk factors for B. cereus-related septicemia. Of these risk factors, the former was extracted because B. cereus may proliferate in PPN. However, the reason why B. cereus-related septicemia frequently develops in the latter, the summer season, remains to be clarified. In this study, we examined the etiology of a high incidence of B. cereus-induced PVC-BSI in the summer.

Materials and Methods

Microorganisms employed

The following strains were used: B. cereus ATCC 11778, a total of 28 clinical isolates of B. cereus from blood (isolated in A university hospital and B university hospital), E. coli ATCC 25922, Klebsiella pneumoniae IFO 3318, Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853, Serratia marcescens IFO 3046, and Candida albicans IFO 1386.

Test solutions

3 types of PPN ((Bfluid® Injection, Otsuka Pharmaceutical Factory, Inc., Tokushima, Japan; Paresafe® and Pareplus®, AY Pharm, Co., Tokyo, Japan), soybean oil (Intralipos® 20%, Otsuka Pharmaceutical Factory, Inc.), albumin (Albumin 25% i.v. 5 g/20 mL- Benesis®, Japan Blood Products Organization., Tokyo, Japan), acetated Ringer's solution (Solacet® F, Terumo Co., Tokyo, Japan), normal saline (Isotonic Sodium Chloride Solution “Hikari®”, Hikari Pharmaceutical Co., Tokyo, Japan), 5% glucose (5% Glucose Injection PL "Fuso®", Fuso Pharmaceutical Industries, Ltd. Osaka, Japan), distilled water (Sterile Water for Injection®, Hikari Pharm. Co.), and 2 kinds of total parenteral nutrition (Elneopa-NF® No.2 Injection, Otsuka Pharmaceutical Factory, Inc., ; Fulcaliq® 2. Terumo Co.,) were used.

Viability of microorganisms in infusion solutions

All microbes used in the experiment were cultured on trypticase soy agar (TSA; Eiken Chemical Co., Tochigi, Japan) for 1-2 days at 35ºC, scraped into sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and centrifuged three times at 3,000 rpm for 10 min to remove the growth medium. Resuspension was carried out in PBS, yielding a concentration of approximately 104-105 colony forming units (CFUs)/mL. Next, 0.05 mL of the resuspension was added to 4.95 mL of each infusion solution. The test solutions were incubated at 20 and 30ºC, and plate counts were performed at 6, 24, 48 h. Each sample was diluted 10-, 102-, 103-, 104-, 105-, and 106- fold in normal saline. Pipettes were used to transfer 0.25 mL of undiluted or diluted samples to TSA. The plates were streaked with a glass 'hockey stick' and incubated at 35ºC for 1-2 days for measurement of the number of viable microorganisms. Each experiment was repeated 3 times and the mean of the 3 repeats was calculated.

Contaminated towels with B. cereus

We had initially observed that hospital bed bath towels shipped from the laundry service factory yield B. cereus. The bed bath towels were prepared by the laundry service, washing in high temperature at 80 ºC for 10 minutes, per regulatory guidelines in Japan. Approximately 1.3 × 103 CFUs / cm2 of B. cereus was found on the towels.

Transfer of B. cereus from a contaminated towel to the skin, and disinfection of B. cereus on the skin by alcohol

This study was conducted with the participation of volunteer pharmaceutical students and staff from the Sanyo-Onoda City University Ethics Review Committee (Title: Attachment of B. cereus to the skin related to bed bathing with B. cereus-contaminated towels, Approval date: September, 2022, Examination certificate management number: 22001).

In 12 subjects (volunteers), we initially screened for presence or absence of B. cereus on subject skin by wiping bilateral forearms (5 cm × 10 cm) with a piece of wet sterile gauze (5 cm × 5 cm). This gauze was placed in a bottle containing 20 mL of sterile physiological saline, and ultrasonically treated at 37kHz for 5 min. Subsequently, the solution in the bottles was diluted 10- fold in normal saline. Pipettes were used to transfer 1 mL (0.25 mL × 4) of undiluted or diluted samples to PBCW agar (Eiken Chemical Co., Ltd.) containing egg yolk. The plates were streaked with a glass 'hockey stick' and incubated at 35ºC for 24 h. Additionally, the residual solution was passed through 0.22 µm membrane filters, 5 cm in diameter (Thermo Scientific Nalgene Analytical Filter Unit 0.2 µm, Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, NC, USA), and the filters were placed on PBCW agar containing egg yolk. After incubation at 35ºC for 24 h, the colonies of B. cereus were counted [29].

Next, the following experiment was conducted in the 9 volunteers that we found B. cereus to be absent on the forearms. Two pieces (5 cm × 5 cm) of bed bath towel that were found to be contaminated with 1.3 × 103 CFUs/cm2 of B. cereus were each dampened with 2mL of sterile purified water. Using each piece, each subject's bilateral forearms (5 cm × 10 cm) were wiped. After naturally air drying, the unilateral forearm was wiped with sterile-water-drenched gauze, and the amount of B. cereus in this gauze was investigated to calculate the forearm B. cereus [30]. Additionally, the other forearm was wiped twice with a medical-grade absorbent cotton (4 cm × 8 cm) containing 1.6 mL of ethanol for disinfection (76.9-81.4 vol%), and wiped with a piece of sterile-water-drenched gauze after 1 min. Subsequently, the amount of B. cereus in this gauze was investigated to calculate the forearm CFUs of B. cereus after alcohol disinfection. The amount of B. cereus in the gauze used for wiping was calculated as described above. In 9 volunteers, this test was conducted twice. The forearm CFUs of B. cereus before and after alcohol disinfection was tested using Wilcoxon's signed-rank test.

Results

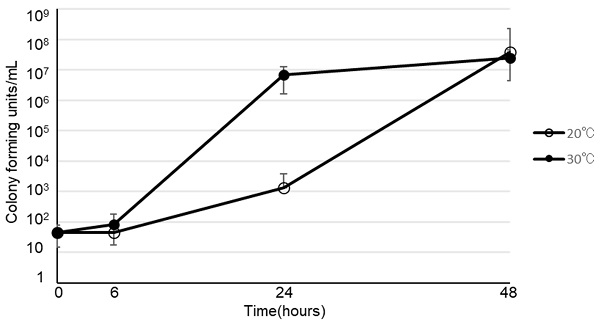

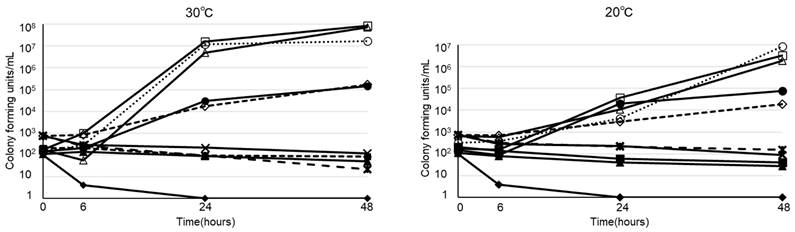

The viability of B. cereus in various types of infusion fluid are shown in Figure 1. At 30ºC, B. cereus promptly proliferated in all 3 types of PPN we tested. Furthermore, B. cereus also proliferated in soybean oil or albumin, but not in acetated Ringer's solution, normal saline, 5% glucose, or total parenteral nutrition. On the other hand, the growth rate at 20ºC was slower than at 30ºC. However, B. cereus proliferated robustly by the 48-hour timepoint in PPN, soybean oil, and albumin, as demonstrated at 30ºC. The viability of 28 clinical isolates of B. cereus in PPN (Bfluid®) are shown in Figure 2. These isolates promptly proliferated in PPN, as shown for a standard strain of B. cereus in Figure 1. After 24 h, these isolates had more rapidly proliferated at 30ºC, but the CFU of bacteria after 48 h was similar between 30ºC and 20ºC.

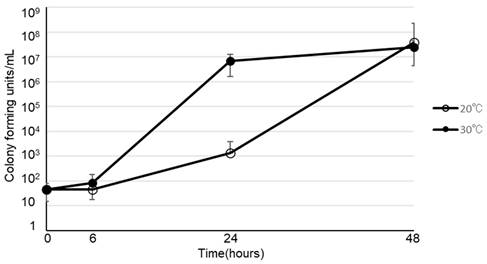

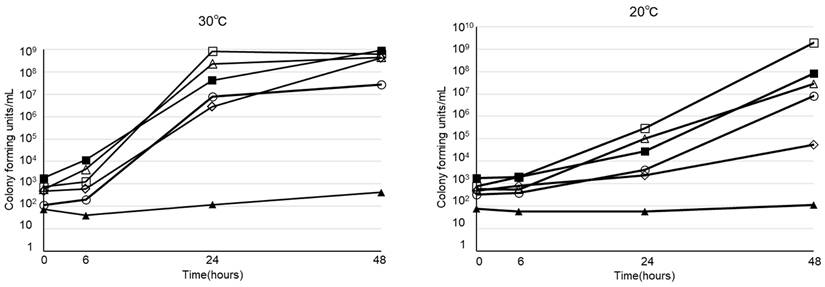

The viability of various microorganisms in PPN (Bfluid®) at 30ºC and 20ºC are shown in Figure 3. Of the 5 strains that we investigated, 4 (E. coli, K. pneumoniae, P. aeruginosa, S. marcescens), excluding C. albicans, promptly proliferated in PPN at 30ºC and 20ºC, as demonstrated for B. cereus.

In 3 of the 12 volunteers, 5, 9, and 17 CFUs of B. cereus were detected from the right forearm (50 cm2) and left forearm (50 cm2), respectively. However, B. cereus was not detected in any of the other 9 subjects. An experiment was conducted in these 9 volunteers. The amount of B. cereus transferred to the skin from the bed bath towel contamination with B. cereus was confirmed in 9 subjects shown in Table 1 (upper row: the right hand was wiped with alcohol, lower row: the left hand was wiped with alcohol). After forearm (50 cm2) wiping with a towel contaminated with 3.3×104 CFUs /25 cm2 of B. cereus, 240 to 1,260 (median 540) CFUs /50 cm2 of B. cereus was detected on the left forearm, and 260 to 3,200 (median 760) CFUs /50 cm2 of B. cereus on the right forearm. Even after disinfection with alcohol, 80 to 620 (median 240) CFUs /50 cm2 of B. cereus was attached to the right forearm, and 120 to 660 (median 320) CFUs /50 cm2 of B. cereus to the left forearm. Disinfection with alcohol significantly decreased the amount of B. cereus found on the skin (p < 0.05, Wilcoxon's signed-rank test). The median values for B. cereus even after ethanol disinfection as CFUs per cm2 on the left arm and right arm was calculated as 6.4 CFUs /cm2 and 4.8 CFUs /cm2 respectively.

Colony forming units of Bacillus cereus from the skin of the forearms (50 cm2) of 9 subjects after application of bed bathing with B. cereus-contaminated towels (3.3×104 cfu/25 cm2)

| Subject No. | Before wiping with alcohol | After wiping with alcohol |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 320 | 480 |

| 1000 | 120 | |

| 2 | 240 | 240 |

| 400 | 320 | |

| 3 | 240 | 80 |

| 3200 | 320 | |

| 4 | 560 | 160 |

| 1400 | 240 | |

| 5 | 540 | 260 |

| 620 | 540 | |

| 6 | 480 | 120 |

| 760 | 180 | |

| 7 | 640 | 120 |

| 260 | 420 | |

| 8 | 720 | 240 |

| 760 | 200 | |

| 9 | 1260 | 620 |

| 1200 | 660 | |

| Median* | 540 | 240*1 |

| 760 | 320*2 |

*1 p =0.02071, *2 p =0.02077 (Wilcoxon signed-rank test)

Viability of Bacillus cereus in peripheral parenteral nutrition (Bfluid® (○), Paresafe® (△), Paleplus® (□)), 5% albumin (◇), soybean oil (●), normal saline (▲), acetated Ringer's solution (■), 5% glucose (◆), and total parenteral nutrition (Elneopa-NF® No. 2 (⨯), Fulcaliq® 2 (⁎))

Viability of twenty-eight strains of clinically isolated Bacillus cereus in peripheral parenteral nutrition (Bfluid®)

Viability of Bacillus cereus (○), E. coli (△), Klebsiella pneumoniae (□), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (◇), Serratia marcescens (■), Candida albicans (▲) in peripheral parenteral nutrition (Bfluid®) at 30°C and 20°C

Discussion

In Japan, double-bag-type PPN products are routinely used. It was shown that a standard strain of B. cereus and its clinical isolates rapidly proliferated in 3 double-bag-type PPN products commercially available in Japan. The growth rate with PPN was equally robust as with fat emulsion or blood preparations (albumin). In this study we demonstrated that B. cereus proliferates in PPN, in addition to other organisms such as E. coli, S. marcescens, K. pneumoniae, and P. aeruginosa, reported by Omotani et al. [31]. In the CDC Guideline for the Prevention of Intravascular Catheter-Related Infections, it is prescribed that tubing used to administer blood, blood products, or lipid emulsion should be replaced within 24 h after the initiation of infusion [32]. Such a regulation may be necessary for PPN products (excluding one-bag-type acidic-pH products).

We had initially observed that hospital bed bath towels shipped from the laundry service factory yield B. cereus. The bed bath towels were prepared by washing in high temperature at 80ºC for 10 min, per regulatory guidelines in Japan. We determined that the washed “clean” bed bath towels we tested harbored approximately 1.3×103 CFUs/cm2 of B. cereus, despite undergoing recommended cleaning protocol set by industry-wide practice. Using these “clean” towels to wipe the volunteer forearms, we determined that 6.4 CFUs (median)/cm2 of B. cereus spores remained on the left and 4.8 CFUs (median)/cm2 on the right skin after wiping with contaminated bed bath towels, despite disinfecting the skins with ethanol wipes afterwards. Our calculation of B. cereus contamination via catheter placement, using the median CFUs /cm2 values, is the following: If a venous indwelling needle (22 G; catheter's cross-sectional area, 0.64 mm2) is inserted to the skin, since the cross-sectional area of the catheter is 0.64 mm2, B. cereus spores may contaminate the indwelling needle at a probability of 0.41% on the left arm and 0.31% on the right arm. If B. cereus contaminates the needle or the site of catheter placement, bloodstream infection is a possible outcome due to rapid proliferation in PPN.

The amount of B. cereus found in the bed bath towel used in this experiment was approximately 103 CFUs /cm2. However, in Japan with a climate of high temperature and high humidity, it is not rare that towels after washing in a cleaning factory may still harbor a higher concentration (104 CFUs /cm2) of B. cereus. If a towel contaminated with approximately 104 CFUs /cm2 of B. cereus was used for a bed bath, the probability at which B. cereus may access the venous indwelling needle will potentially be higher at 3.1 - 4.1% even after wiping the skin with ethanol. Ethanol is ineffective for killing B. cereus spores, and we show here that B. cereus has the potential to proliferate in the infusion fluids.

The detection rate of B. cereus in blood culture-positive samples is 1.2% according to the information published from the Japan Nosocomial Infections Surveillance (JANIS) in 2020. The rates in A and B Hospitals (736 and 904 beds, respectively) were 1.7 and 22.2%, respectively [28]. It is highly probable that bed bath towels contaminated with B. cereus may have contributed to the high outbreak rates of B. cereus in B Hospitals measured in the blood-culture-positive samples. Patients positive for B. cereus on blood culture were mostly patients requiring bed baths. B Hospital's bed bath towels used for bed bathing were from a cleaning factory. Several studies indicated that bed bath towel contamination with B. cereus was frequent in the summer of Japan, China, and Singapore [3-5, 33]. This may be because towels are often contaminated with B. cereus in the summer of Japan, China, and Singapore with a climate of high temperature and high humidity. The bed bath towels used in A Hospitals were independently confirmed by us to have absence of contamination with B. cereus.

B. cereus is regarded as lowly-pathogenic environmental bacteria [34]. However, if infusion fluids such as PPN, is contaminated with B. cereus, this type of bacteria may proliferate, and large numbers of bacteria may invade the body, leading to a serious outcome. We encountered a patient with sepsis in whom 1.0×107 CFUs/mL of B. cereus was detected in the route of administration during PPN administration [17]. Furthermore, several studies indicated that B. cereus sepsis was very serious [6, 7, 12, 14, 15, 16, 19, 20, 35], that there was no treatment response despite the administration of effective antimicrobial drugs [9, 21], and that catheter removal was required [8, 36], suggesting intra-route infusion fluid contamination with bacteria. In many hospitals, infusion fluid contamination with microorganisms during administration is not investigated and is often overlooked. However, physicians must recognize that infusion fluid may be contaminated with microorganisms during use.

We previously reported that measurement of the adenosine triphosphate (ATP) level was useful as a simple method to evaluate infusion fluid contamination with microorganisms [17, 37]. Since infusion fluid contamination can be estimated in a few minutes by measuring the ATP level, infusion fluid that is being administered should be checked using a simple detection method with ATP in patients in whom sepsis is suspected based on findings, such as a high procalcitonin level.

The inadvertent use of contaminated “clean” towels must be avoided, and to ensure quality control, laundry services for hospitals should be required to pass periodic pathogen screening to be given permission to supply and stock sterile towels. In addition, disposable wipes in turn may be particularly useful in the summer seasons. The implementation of standard guidelines that indicate use of sterile bed bath towels or disposable wipes for patients that require PPN would be beneficial for avoiding preventable infections.

Conclusion

The use of B. cereus-contaminated bed bath towels and administration of double-bag-type PPN products may be involved in higher incidence of B. cereus sepsis especially during the summer months in countries such as Japan, China, and Singapore. We demonstrate the ability of B. cereus to proliferate rapidly in PPN products and that higher temperatures lead to faster proliferation rate. If double-bag-type PPN products are contaminated with B. cereus, it is possible that B. cereus may proliferate rapidly in the host via catheter access point. Therefore, the use of sterile bed bath towels must be strongly considered for patients that require PPN.

Competing Interests

The authors have declared that no competing interest exists.

References

1. Bottone EJ. Bacillus cereus, a volatile human pathogen. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23(2):382-398 doi: 10.1128/CMR.00073-09

2. Barrie D, Wilson JA, Hoffman PN. et al. Bacillus cereus meningitis in two neurosurgical patients: an investigation into the source of the organism. J Infect. 1992;25(3):291-297 doi: 10.1016/0163-4453(92)91579-z

3. Dohmae S, Okubo T, Higuchi W. et al. Bacillus cereus nosocomial infection from reused towels in Japan. J Hosp Infect. 2008;69(4):361-367 doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2008.04.014

4. Sasahara T, Hayashi S, Morisawa Y. et al. Bacillus cereus bacteremia outbreak due to contaminated hospital linens. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011;30(2):219-226 doi: 10.1007/s10096-010-1072-2

5. Balm MN, Jureen R, Teo C. et al. Hot and steamy: outbreak of Bacillus cereus in Singapore associated with construction work and laundry practices. J Hosp Infect. 2012;81(4):224-230 doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2012.04.022

6. Akiyama N, Mitani K, Tanaka Y. et al. Fulminant septicemic syndrome of Bacillus cereus in a leukemic patient. Intern Med. 1997;36(3):221-226 doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.36.221

7. Ozkocaman V, Ozcelik T, Ali R. et al. Bacillus spp. among hospitalized patients with haematological malignancies: clinical features, epidemics and outcomes. J Hosp Infect. 2006;64(2):169-176 doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2006.05.014

8. Kassar R, Hachem R, Jiang Y. et al. Management of Bacillus bacteremia: the need for catheter removal. Medicine (Baltimore). 2009;88(5):279-283 doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e3181b7c64a

9. Inoue D, Nagai Y, Mori M. et al. Fulminant sepsis caused by Bacillus cereus in patients with hematologic malignancies: analysis of its prognosis and risk factors. Leuk Lymphoma. 2010;51(5):860-869 doi: 10.3109/10428191003713976

10. Ramarao N, Belotti L, Deboscker S. et al. Two unrelated episodes of Bacillus cereus bacteremia in a neonatal intensive care unit. Am J Infect Control. 2014;42(6):694-695 doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2014.01.025

11. Benusic MA, Press NM, Hoang LM. et al. A cluster of Bacillus cereus bacteremia cases among injection drug users. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2015;26(2):103-104 doi: 10.1155/2015/482309

12. Koizumi Y, Okuno T, Minamiguchi H. et al. Survival of a case of Bacillus cereus meningitis with brain abscess presenting as immune reconstitution syndrome after febrile neutropenia - a case report and literature review. BMC Infect Dis. 2020;20(1):15. doi: 10.1186/s12879-019-4753-1

13. Ikeda M, Yagihara Y, Tatsuno K. et al. Clinical characteristics and antimicrobial susceptibility of Bacillus cereus blood stream infections. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2015;14:43. doi: 10.1186/s12941-015-0104-2

14. Nath SR, Gangadharan SS, Kusumakumary P. et al. The spectrum of Bacillus cereus infections in patients with haematological malignancy. J Acad Clin Microbiol. 2017;19:27-31 doi: 10.4103/jacm.jacm_58_16

15. Glasset B, Herbin S, Granier SA. et al. Bacillus cereus, a serious cause of nosocomial infections: Epidemiologic and genetic survey. PLoS One. 2018;13(5):e0194346. doi: 10.1371/journal. pone.0194346

16. Uchino Y, Iriyama N, Matsumoto K. et al. A case series of Bacillus cereus septicemia in patients with hematological disease. Intern Med. 2012;51(19):2733-2738 doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.51.7258

17. Oie S, Kamiya A, Yamasaki H. et al. Rapid detection of microbial contamination in intravenous fluids by ATP-based monitoring system. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2020;73(5):363-365 doi: 10.7883/yoken.JJID.2019.534

18. Butcher M, Puiu D, Romagnoli M. et al. Rapidly fatal infection with Bacillus cereus/thuringiensis: genome assembly of the responsible pathogen and consideration of possibly contributing toxins. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2021;101(4):115534. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2021.115534

19. Koop L, Garg R, Nguyen T. et al. Bacillus cereus: Beyond gastroenteritis. WMJ. 2021;120(2):145-147

20. Arora S, Thakkar D, Upasana K. et al. Bacillus cereus infection in pediatric oncology patients: A case report and review of literature. IDCases. 2021;26:e01302. doi: 10.1016/j.idcr.2021.e01302

21. Nakashima M, Osaki M, Goto T. et al. Bacillus cereus bacteremia in patients with hematological disorders. Rinsho Ketsueki. 2021;62(3):157-162 doi: 10.11406/rinketsu.62.157

22. Pujol M, Hornero A, Saballs M. et al. Clinical epidemiology and outcomes of peripheral venous catheter-related bloodstream infections at a university-affiliated hospital. J Hosp Infect. 2007;67(1):22-29 doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2007.06.017

23. Sakihama T, Tokuda Y. Use of peripheral parenteral nutrition solutions as a risk factor for Bacillus cereus peripheral venous catheter-associated bloodstream infection at a Japanese tertiary care hospital: a Case-Control Study. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2016;69(6):531-533 doi: 10.7883/yoken.JJID.2015.489

24. Kutsuna S, Hayakawa K, Kita K. et al. Risk factors of catheter-related bloodstream infection caused by Bacillus cereus: Case-control study in 8 teaching hospitals in Japan. Am J Infect Control. 2017;45(11):1281-1283 doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2017.04.281

25. Yamada K, Shigemi H, Suzuki K. et al. Successful management of a Bacillus cereus catheter-related bloodstream infection outbreak in the pediatric ward of our facility. J Infect Chemother. 2019;25(11):873-879 doi: 10.1016/j.jiac.2019.04.013

26. Kato K, Matsumura Y, Yamamoto M. et al. Erratum to: Seasonal trend and clinical presentation of Bacillus cereus bloodstream infection: association with summer and indwelling catheter. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2016;35(5):875-883 doi: 10.1007/s10096-016-2618-8

27. Matsumoto S, Suenaga H, Naito K. et al. Management of suspected nosocomial infection: an audit of 19 hospitalized patients with septicemia caused by Bacillus species. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2000;53(5):196-202

28. Nakamura I, Takahashi H, Sakagami-Tsuchiya M. et al. The seasonality of peripheral venous catheter-related bloodstream infections. Infect Dis Ther. 2021;10(1):495-506 doi: 10.1007/s40121-021-00407-9

29. Oie S, Yanagi C, Matsui H. et al. Contamination of environmental surfaces by Staphylococcus aureus in a dermatological ward and its preventive measures. Biol Pharm Bull. 2005;28(1):120-123 doi: 10.1248/bpb.28.120

30. Oie S, Kamiya A. Microbial contamination of brushes used for preoperative shaving. J Hosp Infect. 1992;21(2):103-110 doi: 10.1016/0195-6701(92)90029-l

31. Omotani S, Tani K, Nagai K. et al. Water soluble vitamins enhance the growth of microorganisms in peripheral parenteral nutrition solutions. Int J Med Sci. 2017;14(12):1213-1219 doi: 10.7150/ijms.21424

32. O'Grady NP, Alexander M, Dellinger EP. et al. Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections. Centers for disease control and prevention. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2002;51(RR-10):1-29

33. Cheng VCC, Chen JHK, Leung SSM. et al. Seasonal outbreak of Bacillus bacteremia associated with contaminated linen in Hong Kong. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64(suppl_2):S91-S97 doi: 10.1093/cid/cix044

34. Weinstein MP, Towns ML, Quartey SM. et al. The clinical significance of positive blood cultures in the 1990s: a prospective comprehensive evaluation of the microbiology, epidemiology, and outcome of bacteremia and fungemia in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24(4):584-602 doi: 10.1093/clind/24.4.584

35. Zhang JW, Zeng YX, Liang JY. et al. Rapidly progressive, fata infection caused by Bacillus cereus in a patient with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Clin Lab. 2018;64(10):1761-1764 doi: 10.7754/Clin.Lab.2018.180528

36. Gurler N, Oksuz L, Muftuoglu M. et al. Bacillus cereus catheter related bloodstream infection in a patient with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2012;4(1):e2012004. doi: 10.4084/MJHID.2012.004

37. Oie S, Kouda K, Furukawa H. et al. Rapid detection of Candida parapsilosis contamination in the infusion fluid. Clin Nurs Stud. 2018;6(4):80-83 doi: 10.5430/cns.v6n4p80

Author contact

![]() Corresponding author: Shigeharu Oie, Ph.D, Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Sanyo-Onoda City University, 1-1-1, Daigakudori, Sanyo-Onoda 756-0884, Japan. Tel.: +81-836-39-9156, Fax: +81-836-88-3400; E-mail: oiesocu.ac.jp

Corresponding author: Shigeharu Oie, Ph.D, Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Sanyo-Onoda City University, 1-1-1, Daigakudori, Sanyo-Onoda 756-0884, Japan. Tel.: +81-836-39-9156, Fax: +81-836-88-3400; E-mail: oiesocu.ac.jp

Global reach, higher impact

Global reach, higher impact