Impact Factor

ISSN: 1449-1907

Int J Med Sci 2018; 15(14):1640-1647. doi:10.7150/ijms.27834 This issue Cite

Research Paper

The effect of the primary tumor location on the survival of colorectal cancer patients after radical surgery

1. Department of Radiation and Medical Oncology, the First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University, Wenzhou, China, 325000.

2. Department of Oncology Medicine, Yueqing Third People's Hospital, Wenzhou, China, 325000

*These authors contributed equally

Received 2018-1-27; Accepted 2018-2-9; Published 2018-11-4

Abstract

Background and Objectives: Colorectal cancer is one of the most common cancers and the leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide. The impact of the primary tumor location on the prognosis of patients with colorectal cancer has long been a concern, but studies have led to conflicting conclusions.

Methods: In total, 465 colorectal cancer patients who received radical surgery were reviewed in this study. Enrolled patients were divided into two groups according to the tumor location. Disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) were analyzed via the Kaplan-Meier method. A Cox regression model was employed to evaluate the independent prognostic factors for DFS and OS.

Results: The right colorectal cancer (RCC) and left colorectal cancer (LCC) groups comprised 202 and 140 patients, respectively. Univariate and multivariate analyses revealed that the tumor location and TNM stage were independent predictors of DFS and OS. Subgroup analyses by stage demonstrated that there were significant differences in DFS and OS between patients with stage II and III RCC and LCC, but not for those with stage I colorectal cancer.

Conclusions: Patients with stage II and III LCC had better survival than those with RCC. However, this improvement in DFS and OS was not observed in patients with stage I colorectal cancer.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer, Tumor location, Surgery, Overall survival, Disease-free survival

Introduction

Colorectal cancer is the third most common cancer and the second leading cause of cancer-related death in the United States, with an incidence of 134490 new cases and approximately 49,190 deaths per year, and colorectal cancer accounts for approximately 36.5% of new cancer cases [1,2]. In China, colorectal cancer is the fifth most common malignant neoplasm [3].

Surgery is considered the gold standard for treatment of colorectal cancer. For resectable non-metastatic colorectal cancer, the preferred surgical procedure is colectomy with en bloc removal of the regional lymph nodes [4]. Another choice is laparoscopic colectomy. No evidence has shown that the different traditional surgical methods impact the outcome [5, 6]. Adjuvant therapy is not recommended for patients with early-stage colorectal cancer but is recommended for patients with advanced stage disease [7, 8].

There are various embryological and biological differences between left-sided colorectal cancer (LCC) and right-sided colorectal cancer (RCC) [9]. RCC occurs in the cecum, ascending colon, and proximal two-thirds of the transverse colon, which arise from the embryonic midgut and receive blood perfusion from the superior mesentery artery, whereas LCC occurs in the distal one-third of the transverse colon, descending colon, sigmoid colon and rectum, which arise from the embryonic hindgut and are perfused by the inferior mesentery artery [10]. Studies have revealed that there are different pathologies and genomic patterns between LCC and RCC [11, 12]. However, the potential influence of these differences on prognosis has not been validated. Recently, studies have demonstrated that RCC presents a significantly worse prognosis than LCC in patients with stage IV disease [13]. Nonetheless, it remains unknown whether the primary tumor location affects the outcome for patients with stage I-III disease, particularly after radical surgery.

In this study, patients with colorectal cancer who underwent primary tumor radical resection were retrospectively reviewed to evaluate and compare the prognosis and survival factors for patients with stage I-III RCC and LCC after radical surgery.

Patients and Methods

Patients

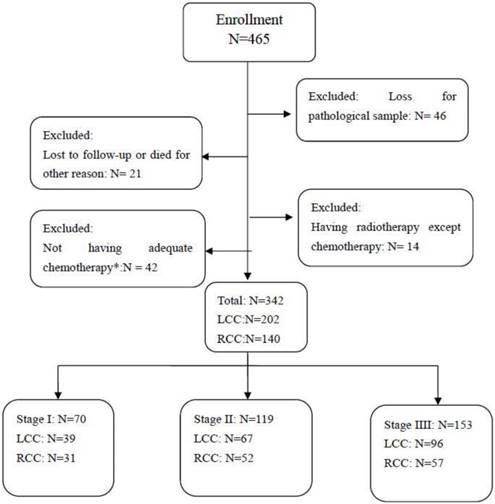

Consecutive patients diagnosed with colorectal cancer at the authors' hospital from Jan. 2011 to May 2014 were retrospectively reviewed. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are presented as a flow diagram in Figure I. The eligibility criteria were as follows: received radical surgery for colorectal cancer; PS≤2; had no serious dysfunction of major organs (e.g., heart failure or uremia); had an appropriate course of chemotherapy (Patients with stage I or low-risk stage II disease did not require adjuvant therapy. Patients with high-risk stage II and stage III disease should receive chemotherapy for at least 4-6 courses). Patients who received radiotherapy or without complete follow-up data were excluded.

Available variables, including routine blood test, liver and kidney function test, blood levels of tumor biomarkers, chest/abdominal computed tomography (CT), and colonoscopy if necessary, were regularly assessed at follow-up. For patients with stage I disease, colonoscopy was required at 1 year and then repeated at 3 years and every 5 years thereafter. In the case of a finding of advanced adenoma, colonoscopy was repeated every 1 year. Patients with stage II and III disease underwent surgery, physical examination and assessment of tumor biomarkers, such as carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and cancer antigen 199 (CA-199), which should be assessed every 3 months for 2 years and then every 6 months for a total of 5 years. Colonoscopy was required 1 year after cancer resection and repeated at 3 years and then every 5 years thereafter. In the case of a finding of advanced adenoma with follow-up colonoscopy, colonoscopy was repeated every 1 year. Assessment as mentioned above during follow-up was performed once every 3-6 months within the first 2 years after surgery, then every 6 months from the third to fifth years, and once a year thereafter. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the authors' hospital.

Study design

Enrolled patients were divided into two groups according to the location of the primary tumor: left-sided and right-sided colorectal cancer groups. The clinicopathologic characteristics of the patients in the two groups were balanced according to gender, age at diagnosis, and pathological diagnosis after surgery, including pathologic type, subtype, histological type, TNM classification (according to the 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM staging system), and tumor grade.

Statistical analysis

The endpoints for this study were disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS). The former was defined as the interval from the date of surgery to the date of the first recurrence or distant metastasis or death from colorectal cancer. The latter was defined as the interval from the date of diagnosis to death or to the date of the last follow-up.

The correlation between clinical pathological characteristics and tumor location (RCC vs LCC) according to the various cancer stages was calculated with Student's t-test for continuous variables or a chi-square test for categorical data. DFS and OS were analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier survival method. The Cox proportional hazards model was used for univariate and multivariate analyses to identify the independent prognostic factors for DFS and OS. Statistical analyses were carried out with SPSS 22.0 software. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant, and robust estimates of the standard error were used in all regression analyses.

Results

Patient characteristics

Among 465 patients diagnosed with colorectal cancer and who underwent radical surgery from Jan. 2011 to May 2014, 342 were enrolled in this study. Forty-six patients due to the loss of pathological samples, 21 patients due to being lost to follow-up, 14 patients who received radiotherapy and 42 patients without adequate chemotherapy were excluded (Figure 1). Of the 342 enrolled patients, the number of patients in stage I, stage II, and stage III was 70 (20.5%), 119 (34.8%), and 153 (44.7%), respectively. There were 140 (40.9%) patients with RCC and 202 with LCC (Figure 1).

Flow Diagram of the Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria. *Patients with stage I disease and patients with low-risk stage II disease are not required to receive adjuvant therapy. Patients with high-risk stage II or stage III disease can receive at least 4-6 courses of chemotherapy. RCC=right-side colorectal cancer; LCC=left-side colorectal cancer.

All the patients underwent radical resection via either traditional surgery or laparoscopic colectomy. Patients with stage I and low-risk stage II disease did not receive adjuvant therapy after surgery. Patients with high-risk stage II disease, defined as those with poor prognostic features, and stage III disease, were treated with adjuvant chemotherapy comprising an infusion of fluorouracil (5-FU), leucovorin (LV), and oxaliplatin (FOLFOX) (n=69, 20.2%) or oral capecitabine and an infusion of oxaliplatin (Xelox) (n=173, 50.6%). Overall, 87 (45.6%) patients received 4 cycles chemotherapy, and 104 (54.4%) patients received 4-8 cycles chemotherapy.

Outcomes stratified by stage

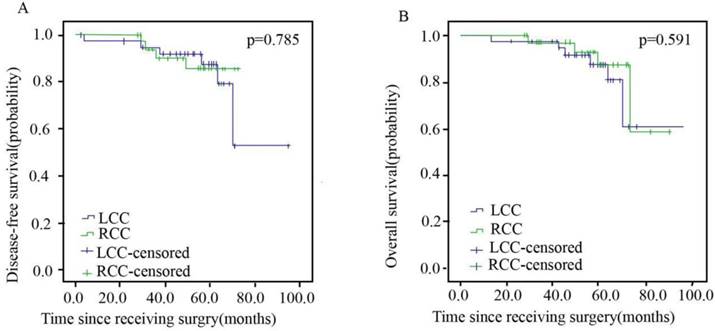

Patients in stage I, II and III between the RCC and LCC groups were well balanced with regard to gender, age, tumor grade, subtype, histological type, T-stage, N-stage, chemotherapy regimen and chemotherapy cycle. The characteristics of patients with stage I disease are shown in Table 1. Overall, 55.7% (n=39) and 44.3% (n=31) of the patients were in the LCC and RCC arms, respectively. The DFS and OS of stage I patients are presented in Figure 2, with no significant differences observed between the two arms.

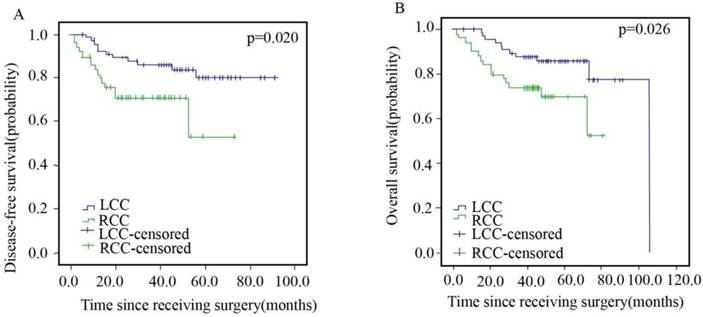

Of the 119 patients in stage II, 67 (56.3%) and 52 (43.7%) patients were in the LCC and RCC arms, respectively, with no significant differences in chemotherapy regimen and chemotherapy cycle (Table 2). The DFS and OS of stage II patients are presented in Figure 3. The patients in the LCC arm showed better DFS (HR=2.500; 95% CI, 1.123-5.563; p=0.020) and OS (HR=2.430; 95% CI, 1.087-5.433; p=0.026) than those in the RCC arm.

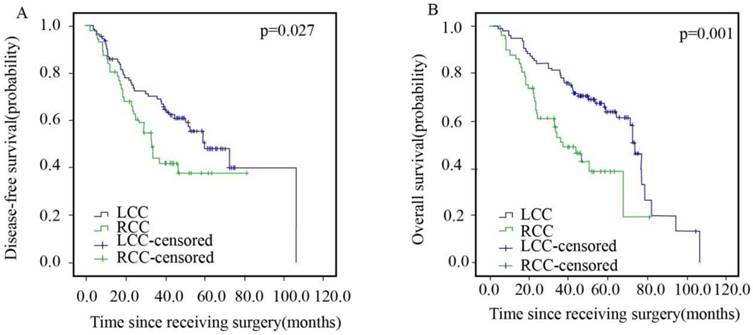

The detailed characteristics of 153 diffuse type patients in stage III are presented in Table 3. The average median DFS and OS for patients in the LCC and RCC arms were 59.5 months vs. 32.9 months and 73.5 months vs. 36.7 months, respectively, as shown in Figure 4. The patients in the LCC arm had a better DFS (HR=1.687, 95% CI: 1.057-2.693, p=0.027) and OS (HR=2.273, 95% CI: 1.405-3.677, p=0.001) than those in the RCC arm.

Clinicalpathological Characteristics of 70 Colorectal Cancer Patients with Stage I by Tumor Location

| Characteristics | Total (%) | LCC (%) | RCC (%) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | 70(100%) | 39(100%) | 31(100%) | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 39(55.7%) | 22(56.4%) | 17(54.8%) | |

| Female | 31(44.3%) | 17(43.6%) | 14(45.2%) | 0.895 |

| Age | ||||

| <60 | 38(54.3%) | 22(56.4%) | 16(51.6%) | |

| ≥60 | 32(45.7%) | 17(43.6%) | 15(48.4%) | 0.689 |

| Tumor grade | ||||

| Poorly or undifferentiated | 23(32.9%) | 12(30.8%) | 11(35.5%) | |

| Well or moderately differentiated | 47(67.1%) | 27(69.2%) | 20(64.5%) | 0.677 |

| Subtypes | ||||

| Ulcerative-type | 42(60.0%) | 25(64.1%) | 17(54.8%) | |

| Unulcerative-type | 28(40.0%) | 14(35.9%) | 14(45.2%) | 0.432 |

| Histological type | ||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 65(92.9%) | 37(94.9%) | 28(90.3%) | |

| Unadenocarcinoma | 5(7.1%) | 2(5.1%) | 3(9.7%) | 0.463 |

| T-stage | ||||

| Tis, T1, T2 | 70(100%) | 39(100%) | 31(100%) | |

| T3, T4 | 0(0%) | 0(0%) | 0(0%) | - |

| N-stage | ||||

| N0, N1a+b | 70(100%) | 39(100%) | 31(100%) | |

| N1c, N2 | 0(0%) | 0(0%) | 0(0%) | - |

Disease-free Survival (A) and Overall Survival (B) of Patients with Left- and Right sided Colorectal Cancer in Stage I.

Disease-free Survival (A) and Overall Survival (B) of Patients with Left- and Right sided Colorectal Cancer in Stage II.

Disease-free Survival (A) and Overall Survival (B) of Patients with Left- and Right sided Colorectal Cancer in Stage III.

Clinicalpathological Characteristics of 119 Colorectal Cancer Patients with Stage II by Tumor Location

| Clinicopathologic Variable | Total (%) | LCC (%) | RCC (%) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | 119(100%) | 67(100%) | 52(100%) | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 60(50.4%) | 37(55.2%) | 23(44.2%) | |

| Female | 59(49.6%) | 30(44.8%) | 29(55.8%) | 0.234 |

| Age | ||||

| <60 | 59(49.6%) | 32(47.8%) | 27(51.9%) | |

| ≥60 | 60(50.4%) | 35(52.2%) | 25(48.1%) | 0.652 |

| Tumor grade | ||||

| Poorly or undifferentiated | 26(21.8%) | 15(22.4%) | 11(21.2%) | |

| Well or moderately differentiated | 93(78.2%) | 52(77.6%) | 41(78.8%) | 0.872 |

| Subtypes | ||||

| Ulcerative-type | 79(66.4%) | 44(65.7%) | 35(67.3%) | |

| Unulcerative-type | 40(33.6%) | 23(34.3%) | 17(32.7%) | 0.851 |

| Histological type | ||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 113(95.0%) | 62(92.5%) | 51(98.1%) | |

| Unadenocarcinoma | 6(5.0%) | 5(7.5%) | 1(1.9%) | 0.343 |

| T-stage | ||||

| Tis, T1, T2 | 9(7.6%) | 6(9.0%) | 3(5.8%) | |

| T3, T4 | 110(92.4%) | 61(91.0%) | 49(94.2%) | 0.762 |

| N-stage | ||||

| N0, N1a+b | 5(4.2%) | 2(3.0%) | 3(5.8%) | |

| N1c, N2 | 114(95.8%) | 65(97.0%) | 49(94.2%) | 0.772 |

| Recurrent risk | ||||

| Low-risk | 30(25.2%) | 21(31.4%) | 9(17.3%) | |

| High-risk | 89(74.8%) | 46(68.6%) | 43(82.7%) | 0.080 |

| Chemotherapy regimens(high-risk) | ||||

| Xelox | 58(48.7%) | 32(47.8%) | 26(50.0%) | |

| Folfox | 31(26.1%) | 14(20.8%) | 17(32.7%) | 0.368 |

| Chemotherapy cycle (high-risk) | ||||

| 4 cycles | 23(19.3%) | 11(16.4%) | 12(23.1%) | |

| 4-8 cycles | 66(55.5%) | 35(52.2%) | 31(59.6%) | 0.667 |

Univariate and multivariate analysis

Table 4 shows the result of univariate and multivariate analyses. Gender and tumor grade were progression factors of OS according to univariate analysis. TNM stage was associated with DFS and OS according to multivariate analysis (both p<0.001).

Discussion

Recently, much attention has been paid to the differences in clinical presentation, patient demographics and epidemiological, morphological and molecular characteristics between left- and right-sided colorectal cancers. This study demonstrated that patients with stage II or III left-sided colorectal cancer had better survival than those with right-sided colorectal cancer after radical resection. However, no significant differences were observed between these two groups for patients with stage I colorectal cancer.

The impact of primary tumor location on the prognosis of patients with colorectal cancer has long been a concern [14-16], but studies have reported conflicting conclusions [17]. A recent meta-analysis that included 15 studies demonstrated that patients with right-sided colon cancer had inferior OS (HR=1.14) compared with those with left-sided colon cancer [18]. Karim et al. [16] analyzed data from 6365 patients and found no difference in long-term survival between RCC and LCC patients. Warschkow et al. [12] noted that patients with LCC had a higher risk of mortality than those with RCC across all stages.

Clinicalpathological Characteristics of 153 Colorectal Cancer Patients with Stage III by Tumor Location

| Clinicopathologic Variable | Total(%) | LCC(%) | RCC(%) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | 153(100%) | 96(100%) | 57(100%) | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 87(56.9%) | 59(61.5%) | 28(49.1%) | |

| Female | 66(43.1%) | 37(38.5%) | 29(50.9%) | 0.136 |

| Age | ||||

| <60 | 71(46.4%) | 46(47.9%) | 25(43.9%) | |

| ≥60 | 82(53.6%) | 50(52.1%) | 32(56.1%) | 0.627 |

| Tumor grade | ||||

| Poorly or undifferentiated | 50(32.7%) | 27(28.1%) | 23(40.4%) | |

| Well or moderately differentiated | 103(67.3%) | 69(71.9%) | 34(59.6%) | 0.119 |

| Subtypes | ||||

| Ulcerative-type | 110(71.9%) | 70(72.9%) | 40(70.2%) | |

| Unulcerative-type | 43(28.1%) | 26(27.1%) | 17(29.8%) | 0.715 |

| Histological type | ||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 149(97.4%) | 93(96.9%) | 56(98.2%) | |

| Unadenocarcinoma | 4(2.6%) | 3(3.1%) | 1(1.8%) | 0.607 |

| T-stage | ||||

| Tis, T1, T2 | 29(19.0%) | 17(17.7%) | 12(21.1%) | |

| T3, T4 | 124(81.0%) | 79(82.3%) | 45(78.9%) | 0.610 |

| N-stage | ||||

| N0, N1a+b | 63(41.2%) | 43(44.8%) | 20(35.1%) | |

| N1c, N2 | 90(58.8%) | 53(55.2%) | 37(64.9%) | 0.238 |

| Chemotherapy regimens | ||||

| Xelox | 115(75.2%) | 75(78.1%) | 40(70.2%) | |

| Folfox | 38(24.8%) | 21(21.9%) | 17(29.8%) | 0.271 |

| Chemotherapy cycle | ||||

| 4 cycles | 64(41.8%) | 38(39.6%) | 26(45.6%) | |

| 4-8 cycles | 89(58.2%) | 58(60.4%) | 31(54.4%) | 0.465 |

In this study, no significant differences in DFS and OS were observed between the LCC and RCC arms for patients with stage I colorectal cancer. This was consistent with the results of a study by Weiss et al. [19] in which the mortality difference between patients with stage I right- or left-sided cancer was not significant (p=0.211). However, for patients with stage II colorectal cancer, a better prognosis for those with LCC was observed compared with those with RCC in terms of DFS (HR=2.500; 95% CI, 1.123-5.563; p=0.020) and OS (HR=2.430; 95% CI, 1.087-5.433; p=0.026). In contrast, Weiss et al. [19] and Warschkow et al.[12] reported that patients with stage II RCC had a lower mortality rate than those with stage II LCC (p=0.001). On the other hand, Weiss et al.[20] reported that there was no survival difference between LCC and RCC patients. These controversial conclusions concerning patients with stage II colorectal cancer may result from different adjuvant chemotherapy modalities applied in different studies, since there is no universally accepted adjuvant treatment modality for these patients. In this study, enrolled patients underwent radical surgical resection and received 4-8 cycles of standard adjuvant chemotherapy regularly without any radiotherapy.

For patients with stage III colorectal cancer, our study also found that patients with LCC had a better prognosis than those with RCC in terms of DFS (HR=1.687, 95% CI: 1.057-2.693, p=0.027) and OS (HR=2.273, 95% CI: 1.405-3.677, p=0.001). This was consistent with the study of Price et al.[17], in which an inferior OS was observed for patients with RCC compared with those with LCC. Consistently, a previous meta-analysis [15, 18] indicated that left-sided primary tumors were associated with a significantly reduced risk of patient death (HR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.79-0.84; p<0.001). However, Warschkow et al. [12] found that the prognosis of patients with stage III RCC and LCC was similar (overall: HR=0.99, 95% CI: 0.95-1.03 and cancer-specific: HR=1.04, 95% CI: 0.99-1.09). The difference between these studies may contribute to different eligibility criteria and therapeutic strategies.

The univariate and multivariate analyses performed in our study indicated that gender and tumor grade were progression factors in OS, and TNM stage was associated with DFS and OS. Similarly, Valentine et al. [21] and Warschkow et al. [12] indicated that age, marital status and TNM stage were associated with survival. The specific mechanism underlying the different prognoses between RCC and LCC is still unclear, although studies have stated that LCC and RCC are two distinct diseases [12, 22].

Recent genetic studies have revealed distinguishable genomic patterns between LCC and RCC, including differences in microsatellite instability (MSI), chromosome instability (CIN), and CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP) [23, 24]. Accumulating evidence has demonstrated that MSI is an independent predictor of survival and is predominantly seen in right-sided colon cancer, while MSI-H is suggested to contribute to RCC carcinogenesis [25, 26]. CIN results from abnormal structure or number of chromosomes, which leads to a series of genetic changes. Accordingly, CIN contributes to approximately 75% of LCC and 30% of RCC [22, 27]. CIMP has also been suggested to contribute to RCC carcinogenesis and has been found to be an independent risk factor for poor prognosis in colorectal cancer patients [28, 29]. Certainly, more sophisticated molecular classifications are needed to reveal the progression differences between patients with LCC and RCC.

One limitation of the current study is that the study is retrospective in design. Another is that the study includes only patients from a single institution, and thus, the number of patients enrolled may be not sufficient. Moreover, the follow-up duration of the study may be not sufficiently long. The confounding factors of various treatments related to outcome could not be fully evaluated. Therefore, further research with a large population is needed to evaluate the relationship between tumor location and prognosis for patients with colorectal cancer. In addition, more genetic studies are needed to further investigate the mechanism underlying the progression differences between LCC and RCC.

Conclusion

The present study demonstrated that patients with stage II and III LCC had better survival than those with RCC after radical resection, but this difference was not observed in patients with stage I colorectal cancer. Therefore, the primary site of colorectal cancer may be a helpful factor in determining the treatment of patients with colorectal cancer.

Univariate and Multivariate Analysis for Disease-free Survival (DFS) and Overall Survival (OS) of All Patients

| DFS | OS | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate | Multivariate | Univariate | Multivariate | |||||

| Parameters | HR(95%CI) | p | HR(95%CI) | p | HR(95%CI) | p | HR(95%CI) | p |

| Gender | 1.267(0.869-1.848) | 0.219 | 1.451(0.908-2.318) | 0.120 | 1.581(1.074-2.327) | 0.020 | 1.876(1.156-3.045) | 0.101 |

| Age | 1.591(1.087-2.329) | 0.170 | 1.446(0.929-2.250) | 0.102 | 1.572(1.047-2.134) | 0.120 | 1.343(0.855-2.110) | 0.200 |

| Tumor grade | 0.739(0.473-1.156) | 0.185 | 0.791(0.447-1.402) | 0.423 | 0.627(0.397-0.990) | 0.045 | 0.679(0.379-1.216) | 0.193 |

| Subtypes | 1.029(0.690-1.534) | 0.889 | 1.236(0.763-2.000) | 0.389 | 1.039(0.696-1.551) | 0.852 | 1.195(0.732-1.950) | 0.476 |

| Histological type | 1.367(0.599-3.122) | 0.458 | 1.922(0.659-5.607) | 0.231 | 0.843(0.363-1.959) | 0.692 | 1.282(0.417-3.942) | 0.664 |

| T-stage | 2.837(1.759-4.578) | <0.001 | 2.305(1.036-5.131) | 0.041 | 2.796(1.734-4.506) | <0.001 | 1.991(0.904-4.382) | 0.087 |

| N-stage | 2.101(1.426-3.096) | <0.001 | 1.041(0.615-1.763) | 0.881 | 1.927(1.307-2.841) | 0.001 | 0.951(0.556-1.626) | 0.854 |

| TNM stage | 2.497(1.867-3.340) | <0.001 | 3.104(1.772-5.437) | <0.001 | 2.354(1.759-3.150) | <0.001 | 2.915(1.672-5.081) | <0.001 |

| The following data for only stage II, III patients received chemotherapy | ||||||||

| XELOX/FOLFOX | 0.808(0.571-1.144) | 0.229 | 0.676(0.458-0.997) | 0.058 | 0.912(0.650-1.279) | 0.594 | 0.869(0.590-1.280) | 0.477 |

| 4courses/4-8 courses | 1.034(0.625-1.711) | 0.897 | 1.091(0.641-1.857) | 0.748 | 0.818(0.493-1.357) | 0.436 | 0.886(0.523-1.500) | 0.652 |

CI=confidence interval, HR=hazard ratio, DFS=disease-free survival, OS=overall survival

Abbreviations

LCC: left-sided colorectal cancer; RCC: right-sided colorectal cancer; DFS: disease-free survival; OS: overall survival; AJCC: American Joint Committee on Cancer; vs: versus; HR: hazard ratio; CI: confidence interval; CSS: cancer-specific survival; CEA: carcinoembryonic antigen; CA-199: cancer antigen 199; MSI: microsatellite instability; CIN: chromosome instability; CIMP: CpG island methylator phenotype.

Acknowledgements

The study was partially founded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 11675122) and Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (grant numbers LY16H160046 and Y17H160051).

Availability of data and material

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author contributions

XC and DG acquired and analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. MC made contributions to patient follow-up. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics Committee Approval and Patient Consent

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This study was approved by the Regional Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University.

Consent for publication

Written, informed consent was obtained from each patient prior to publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest

References

1. Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM. et al. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69-90

2. Siegle RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. et al. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:7-30

3. Dai Z, Zheng RS, Zou XN. et al. Analysis and prediction of colorectal cancer incidence trend in China. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2012;46:598-603

4. West NP, Hohenberger W, Weber K. et al. Complete mesocolic excision with central vascular ligation produces an oncologically superior specimen compared with standard surgery for carcinoma of the colon. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:272-8

5. Homma S, Kawamata F, Yoshida T. et al. The Balance Between Surgical Resident Education and Patient Safety in Laparoscopic Colorectal Surgery: Surgical Resident's Performance has No Negative Impact. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2017;27:295-300

6. Yamaguchi S, Tashiro J, Araki R. et al. Laparoscopic versus open resection for transverse and descending colon cancer: Short-term and long-term outcomes of a multicenter retrospective study of 1830 patients. Asian J Endosc Surg. 2017;10:268-275

7. Kuebler JP, Wieand HS, O'Connell MJ. et al. Oxaliplatin combined with weekly bolus fluorouracil and leucovorin as surgical adjuvant chemotherapy for stage II and III colon cancer: results from NSABP C-07. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2198-204

8. Twelves C, Wong A, Nowacki MP. et al. Capecitabine as adjuvant treatment for stage III colon cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2696-704

9. Hansen IO, Jess P. Possible better long-term survival in left versus right-sided colon cancer - a systematic review. Dan Med J. 2012;59:A4444

10. Masoomi H, Buchberg B, Dang P. et al. Outcomes of right vs. left colectomy for colon cancer. Gastrointest Srug. 2011;15:2023-8

11. Xiang L, Zhan Q, Zhao XH. et al. Risk factors associated with missed colorectal flat adenoma: a multicenter retrospective tandem colonoscopy study. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:10927-37

12. Warschkow R, Sulz MC, Marti L. et al. Better survival in right-sided versus left-sided stage I - III colon cancer patients. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:554

13. Tejpar S, Stintzing S, Ciardiello F. et al. Prognostic and Predictive Relevance of Primary Tumor Location in Patients With RAS Wild-Type Metastatic Colorectal Cancer: Retrospective Analyses of the CRYSTAL and FIRE-3 Trials. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:194-201

14. Qin Q, Yang L, Sun YK. et al. Comparison of 627 patients with right- and left-sided colon cancer in China: Differences in clinicopathology, recurrence, and survival. Chronic Dis Transl Med. 2017;3:51-59

15. Petrelli F, Tomasello G, Borgonovo K. et al. Prognostic Survival Associated With Left-Sided vs Right-Sided Colon Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:211-219

16. Karim S, Brennan K, Nanji S. et al. Association Between Prognosis and Tumor Laterality in Early-Stage Colon Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:1386-1392

17. Price TJ, Beeke C, Ullah S. et al. Does the primary site of colorectal cancer impact outcomes for patients with metastatic disease? Cancer. 2015;121:830-5

18. Yahagi M, Okabayashi K, Hasegawa H. et al. The Worse Prognosis of Right-Sided Compared with Left-Sided Colon Cancers: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2016;20:648-55

19. Weiss JM, Pfau PR, O'Connor ES. et al. Mortality by stage for right- versus left-sided colon cancer: analysis of surveillance, epidemiology, and end results-Medicare data. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4401-9

20. Weiss JM, Schumacher J, Allen GO. et al. Adjuvant Chemotherapy for Stage II Right- and Left-Sided Colon Cancer: Analysis of SEER-Medicare Data. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:1781-91

21. Nfonsam V, Aziz H, Pandit V. et al. Analyzing clinical outcomes in laparoscopic right vs. left colectomy in colon cancer patients using the NSQIP database. Cancer Treat Commun. 2016;8:1-4

22. Shen H, Yang J, Huang Q. et al. Different treatment strategies and molecular features between right-sided and left-sided colon cancers. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:6470-8

23. Wang HL, Lopategui J, Amin MB. et al. KRAS mutation testing in human cancers: The pathologist's role in the era of personalized medicine. Adv Anat Pathol. 2010;17:23-32

24. Lee MS, Menter DG, Kopetz S. et al. Right Versus Left Colon Cancer Biology: Integrating the Consensus Molecular Subtypes. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2017;15:411-419

25. Yiu AJ, Yiu CY. Biomarkers in Colorectal Cancer. Anticancer Res. 2016;36:1093-102

26. Gatalica Z, Vranic S, Xiu J. et al. High microsatellite instability (MSI-H) colorectal carcinoma: a brief review of predictive biomarkers in the era of personalized medicine. Fam Cancer. 2016;15:405-12

27. Neumann JH, Jung A, Kirchner T. et al. Molecular pathology of colorectal cancer. Pathologe. 2015;36:137-44

28. Juo YY, Johnston FM, Zhang DY. et al. Prognostic value of CpG island methylator phenotype among colorectal cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:2314-27

29. Barault L, Charon-Barra C, Jooste V. et al. Hypermethylator phenotype in sporadic colon cancer: study on a population-based series of 582 cases. Cancer Res. 2008;68:8541-6

Author biographies

Dr. Congying Xie is a professor who has engaged in tumor research for more than 10 years. She obtained her medical degree in 2012. Her current research interests are in esophageal cancer, colorectal cancer and lung cancer. She was invited to give a speech at the IASLC 18th world conference on lung cancer (WCLC) in 2017.

Dr. Dianna Gu obtained her medical degree from the First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University, Wenzhou, China. She obtained her medical degree from the Shanghai Jiao Tong University of China in 2017. Her research is centered on tumor pathophysiology.

![]() Corresponding author: Dr. Xiance Jin, Ph.D., Department of Radiation and Medical Oncology, the First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University, Wenzhou, China, 325000 Phone: 0086-577-88069370, Fax: 0086-577-55578999-664166 E-mail: jinxc1979com Dr. Congying Xie, Ph.D., Department of Radiation and Medical Oncology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University, No.2 Fuxue Lane, Wenzhou, China, 325000 Phone: (0086)13867711881, Fax: 0086-577-55578999-611881E-mail: wzxiecongyingcom

Corresponding author: Dr. Xiance Jin, Ph.D., Department of Radiation and Medical Oncology, the First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University, Wenzhou, China, 325000 Phone: 0086-577-88069370, Fax: 0086-577-55578999-664166 E-mail: jinxc1979com Dr. Congying Xie, Ph.D., Department of Radiation and Medical Oncology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University, No.2 Fuxue Lane, Wenzhou, China, 325000 Phone: (0086)13867711881, Fax: 0086-577-55578999-611881E-mail: wzxiecongyingcom

Global reach, higher impact

Global reach, higher impact