3.2

Impact Factor

ISSN: 1449-1907

Int J Med Sci 2018; 15(6):653-658. doi:10.7150/ijms.23733 This issue Cite

Research Paper

Impact of matrix metalloproteinase-11 gene polymorphisms upon the development and progression of hepatocellular carcinoma

1. Department of Hepatobiliary Surgery, Affiliated Dongyang Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University, Dongyang, Zhejiang, China

2. School of Chinese Medicine, China Medical University, Taichung, Taiwan

3. Department of Orthopedic Surgery, China Medical University Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan

4. Institute of Medicine, Chung Shan Medical University, Taichung, Taiwan

5. School of Medicine, Chung Shan Medical University, Taichung, Taiwan

6. Department of Surgery, Chung Shan Medical University Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan

7. Department of Biomedical Sciences Laboratory, Affiliated Dongyang Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University, Dongyang, Zhejiang, China

8. Department of Medical Research, Chung Shan Medical University Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan

9. Department of Pharmacology, School of Medicine, China Medical University, Taichung, Taiwan

10. Graduate Institute of Basic Medical Science, China Medical University, Taichung, Taiwan

11. Department of Biotechnology, College of Health Science, Asia University, Taichung, Taiwan

# These authors have contributed equally to this work

Received 2017-11-8; Accepted 2018-3-2; Published 2018-4-3

Abstract

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a liver malignancy and a major cause of cancer mortality worldwide. Matrix metalloproteinase-11 (MMP-11), also known as stromelysin-3, plays a critical role during tumor migration, invasion and metastasis. Here, we report on the association between five single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) - rs738791, rs2267029, rs738792, rs28382575, and rs131451 - of the MMP-11 gene and HCC susceptibility, as well as clinical outcomes, in 293 patients with HCC and in 586 cancer-free controls. We found that carriers of the CT+TT allele of the rs738791 variant were at greater risk of HCC compared with wild-type (CC) carriers. Moreover, carriers of at least one C allele (C/T+C/C genotype) at the MMP-11 SNP rs738792 were likely to progress to Child-Pugh B or C grade, while individuals with at least one C allele (C/T+C/C genotype) at the MMP-11 SNP rs28382575 were at higher risk of developing stage III/IV disease, large tumors or lymph node metastasis. We believe that genetic variations in the MMP-11 gene may help to predict early-stage HCC and act as reliable biomarkers for HCC progression.

Keywords: MMP-11 polymorphisms, Hepatocellular carcinoma, Single nucleotide polymorphism, Susceptibility

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the fifth most common cancer amongst men worldwide and the ninth in women, and a major cause of cancer-related mortality [1]. HCC is associated with a low 5-year survival rate and an increasing mortality rate [2, 3]. In Taiwan, HCC is the second leading cause of cancer-associated deaths [4, 5].

Genetic variation plays a key role in HCC susceptibility and development of the disease. The majority of people who are exposed to the well-known infectious, lifestyle or environmental risk factors (i.e., hepatitis B or C virus infection, alcohol abuse or non-alcoholic fatty liver disease associated with obesity, type 2 diabetes or insulin resistance) do not develop HCC, which suggests that individual susceptibility modulates tumorigenesis [4]. Genotype distribution frequency data can be used to map single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) diversity in a population and to examine the risk and development of specific diseases [6]. Emerging reports indicate an association between SNPs in certain genes and the susceptibility and clinicopathological status of HCC. For instance, individuals carrying specific interleukin-18 (IL-18), high-mobility group box protein 1 (HMGB1) or C-C chemokine ligand 4 (CCL4) SNPs are at higher risk of HCC than wild-type carriers [7-9].

Metastasis is a key step in tumor development and the chief cause of mortality for patients with cancer. There are several steps by which cells detach from the primary tumor and form a secondary tumor at a distant site [10]. Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are well-known proteases associated with the breakdown of the extracellular matrix (ECM) surrounding tumor cells [11]. Increasing evidence has indicated that raised levels of MMPs are associated with cancer development and are linked to shorter survival of patients [12].

MMP-11, also known as stromelysin-3, has been observed during wound healing in normal physiologic conditions and in intense tissue remodeling during embryogenesis, as well as tissue involution [13]. However, MMP-11 is unlike most MMP family members which does not cleave major components of the ECM. In addition, the laminin receptor, insulin-like growth factor binding protein 1, collagen VI, and α1-proteinase inhibitor are major substrates of MMP-11 [14]. Upregulation of MMP-11 expression has been found in human carcinomas, such as lung, ovarian, breast, colorectal, and HCC [15, 16]. Genetic polymorphisms of MMP-11 have been indicated in several different cancer types, including oral and breast cancers [17, 18]. Scant research has examined the association between MMP-11 SNPs, HCC risk and prognosis. We therefore conducted a case-control study to evaluate the role of five MMP-11 SNPs on HCC susceptibility and clinicopathological features in a cohort of Chinese Han individuals.

Materials and Methods

Participants

We enrolled 293 patients (cases) presenting with HCC to Chung Shan Medical University Hospital, Taiwan, between 2007 and 2015. A total of 586 anonymized healthy controls (HCs) without a history of cancer were randomly selected from the Taiwan Biobank Project. All study participants were of Chinese Han ethnicity. HCC patients were staged according to the 2010 American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM staging system, which incorporates tumor morphology, the number of lymph nodes affected, and metastases [19]. Before entering the study, each participant provided informed written consent and completed a structured questionnaire about sociodemographic status, cigarette and alcohol use. Liver cirrhosis was diagnosed by biopsy, appropriate sagittal CT or MRI scans, or biochemical evidence of liver parenchymal damage with endoscopic esophageal or gastric varices. The study was approved prior to commencement by Chung Shan Medical University Hospital's Institutional Review Board.

SNP selection

Five SNPs in MMP-11 were selected from the International HapMap Project data for this study. We included the nonsynonymous SNPs rs738792 (Ala38Val) and synonymous SNPs rs28382575 (Pro475Pro) in the coding sequences of the gene. To obtain adequate power to evaluate the potential association, we investigated rs2267029 with minor allelic frequencies of >5%. Furthermore, the rs738791 and rs131451 were selected in this study because the gene polymorphism of the SNP has been found to associate with myopia [20].

Determination of genotypes

Total genomic DNA was isolated from whole blood specimens using QIAamp DNA blood mini kits (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), as per the manufacturer's instructions. This DNA was dissolved in TE buffer (10 mM Tris pH 7.8, 1 mM EDTA) and stored at -20°C until it was subjected to quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis. Five MMP-11 SNPs (rs738791, rs2267029, rs738792, rs28382575, and rs131451) with minor allele frequencies >5% in the HapMap population were selected. The MMP-11 SNPs were examined using the commercially available TaqMan SNP genotyping assay (Applied Biosystems, Warrington, UK), according to the manufacturer's protocols [21].

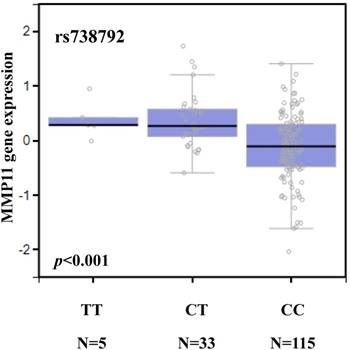

Bioinformatic analysis

Genotype-tissue expression (GTEx) data were used to identify correlations between SNPs and levels of MMP-11 expression [22, 23]. We conducted an investigation into expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs), to determine the functional role of phenotype-associated SNPs.

Statistical analysis

The genotype distribution of each SNP was analyzed for Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium and confirmed by Chi-square analysis. Demographic characteristics were compared between patients and controls using the Mann-Whitney U-test and Fisher's exact test. Associations between genotypes, HCC risk and clinicopathological characteristics were estimated using adjusted odds ratios (AORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) obtained from age- and gender-adjusted multiple logistic regression models. A p value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data were analyzed using SAS statistical software (Version 9.1, 2005; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Demographic characteristics did not differ significantly between the 293 patients with HCC and 586 cancer-free healthy controls (HCs) (Table 1). Significantly fewer (p < 0.001) controls compared with patients reported that they consumed alcohol, but cigarette smoking status did not differ between the two groups (p = 0.809) (Table 1). Compared with controls, significantly higher proportions of HCC patients were positive for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) (12.1% vs 42.3%; p < 0.001) and anti-hepatitis C virus (HCV) antibodies (4.4% vs 47.8%; p < 0.001) (Table 1). At study entry, 205 patients (70.0%) had stage I/II HCC and 88 (30.0%) had stage III/IV disease. Most patients had liver cirrhosis (83.3%) (Table 1).

Demographic characteristics for 586 healthy volunteers (controls) and 293 patients with hepatocellular carcinoma.

| Variable | Controls (N=586) | Patients (N=293) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | Mean ± S.D. | Mean ± S.D. | |

| 59.39 ± 7.45 | 60.08 ± 9.50 | p = 0.284 | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 426 (72.7%) | 213 (72.7%) | |

| Female | 160 (27.3%) | 80 (27.3%) | p = 1.000 |

| Cigarette smoking status | |||

| No | 347 (59.2%) | 171 (58.4%) | |

| Yes | 239 (40.8%) | 122 (41.6%) | p = 0.809 |

| Alcohol consumption | |||

| No | 501 (85.5%) | 184 (62.8%) | |

| Yes | 85 (14.5%) | 109 (37.2%) | p < 0.001* |

| HBsAg | |||

| Negative | 515 (87.9%) | 169 (57.7%) | |

| Positive | 71 (12.1%) | 124 (42.3%) | p < 0.001* |

| Anti-HCV | |||

| Negative | 560 (95.6%) | 153 (52.2%) | |

| Positive | 26 (4.4%) | 140 (47.8%) | p < 0.001* |

| Stage | |||

| I+II | 205 (70.0%) | ||

| III+IV | 88 (30.0%) | ||

| Tumor T status | |||

| T1+T2 | 206 (70.3%) | ||

| T3+T4 | 87 (29.7%) | ||

| Lymph node status | |||

| N0 | 283 (96.6%) | ||

| N1+N2+N3 | 10 (3.4%) | ||

| Metastasis | |||

| M0 | 281 (95.9%) | ||

| M1 | 12 (4.1%) | ||

| Child-Pugh grade | |||

| A | 227 (77.5%) | ||

| B or C | 66 (22.5%) | ||

| Liver cirrhosis | |||

| Negative | 49 (16.7%) | ||

| Positive | 244 (83.3%) |

Mann-Whitney U test or Fisher's exact test was used between healthy controls and patients with HCC.

* p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The distribution of the MMP-11 genotypes between the HCC patients and HCs is shown in Table 2. In the HCs, all genotypic frequencies were in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (p > 0.05). In both patients and controls, most of those with the rs738791 SNP were homozygous for the C/C genotype, most of those with the rs2267029 SNP were homozygous for the G/G genotype, most of those with the rs738792 SNP were homozygous for T/T, most of those with the rs28382575 SNP were homozygous for T/T and most of those with the rs131451 SNP were homozygous for T/T (Table 2). After adjusting for potential confounders, subjects with CT+TT of the MMP-11 rs738791 polymorphism had a 1.389-fold- (95% CI: 1.004-1.921; p < 0.05) higher risk of developing HCC compared to those with C/C homozygotes. However, there were no significant between-group differences as to the proportions of HCC patients with the rs2267029, rs738792, rs28382575 and rs131451 polymorphisms, as compared with HCs (Table 2).

Genotyping and allele frequency of MMP-11 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in controls and patients with hepatocellular carcinoma.

| Variable | Controls (N=586) | Patients (N=293) | Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval)a |

|---|---|---|---|

| rs738791 | |||

| CC | 279 (47.6%) | 121 (41.3%) | 1.000 (reference) |

| CT | 248 (42.3%) | 143 (48.8%) | 1.402 (0.999-1.967) |

| TT | 59 (10.1%) | 29 (9.9%) | 1.332 (0.767-2.312) |

| CT+TT | 307 (52.4%) | 172 (58.7%) | 1.389 (1.004-1.921)b |

| rs2267029 | |||

| GG | 315 (53.8%) | 155 (52.9%) | 1.000 (reference) |

| AG | 228 (38.9%) | 116 (39.6%) | 1.113 (0.798-1.551) |

| AA | 43 (7.3%) | 22 (7.5%) | 0.970 (0.503-1.872) |

| AG+AA | 271 (46.3%) | 138 (47.1%) | 1.092 (0.793-1.505) |

| rs738792 | |||

| TT | 287 (49.0%) | 149 (50.9%) | 1.000 (reference) |

| CT | 244 (41.6%) | 119 (40.6%) | 0.967 (0.693-1.348) |

| CC | 55 (9.4%) | 25 (8.5%) | 0.770 (0.419-1.416) |

| CT+CC | 299 (51.0%) | 144 (49.1%) | 0.933 (0.677-1.284) |

| rs28382575 | |||

| TT | 562 (95.9%) | 281 (95.9%) | 1.000 (reference) |

| CT | 23 (3.9%) | 12 (4.1%) | 0.654 (0.272-1.571) |

| CC | 1 (0.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | - |

| CT+CC | 24 (4.1%) | 12 (4.1%) | 0.621 (0.260-1.483) |

| rs131451 | |||

| TT | 198 (33.8%) | 115 (39.3%) | 1.000 (reference) |

| CT | 278 (47.4%) | 134 (45.7%) | 0.907 (0.640-1.285) |

| CC | 110 (18.8%) | 44 (15.0%) | 0.656 (0.400-1.077) |

| CT+CC | 388 (66.2%) | 178 (60.7%) | 0.841 (0.603-1.172) |

a adjusted for the effects of age and gender.

b p = 0.047.

Next, we compared the distributions of clinical aspects and MMP-11 genotypes in HCC patients. Compared with patients with the T/T genotype, those with at least one polymorphic C allele at the rs738792 SNP (C/T+C/C genotype) were prone to developing moderate to severe liver failure (Child-Pugh B or C grade; p = 0.008) (Table 3). Moreover, carriers of the C/T+C/C genotype of rs28382575 had a higher risk than T/T carriers of developing stage III/IV disease (p = 0.039), large tumors (p = 0.036) or lymph node metastasis (p = 0.001) (Table 4).

Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) associated with clinical status and MMP-11 rs738792 genotypic frequencies in 293 patients with hepatocellular carcinoma.

| Variable | Genotypic frequencies | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TT (N=149) | CT+CC (N=144) | OR (95% CI) | p value | |

| Clinical Stage | ||||

| Stage I/II | 109 (73.2%) | 96 (66.7%) | 1.00 | p = 0.227 |

| Stage III/IV | 40 (26.8%) | 48 (33.3%) | 1.362 (0.825-2.249) | |

| Tumor size | ||||

| ≤T2 | 110 (73.8%) | 96 (66.7%) | 1.00 | p = 0.181 |

| >T2 | 39 (26.2%) | 48 (33.3%) | 1.410 (0.852-2.333) | |

| Lymph node metastasis | ||||

| No | 146 (98.0%) | 137 (95.1%) | 1.00 | p = 0.193 |

| Yes | 3 (2.0%) | 7 (4.9%) | 2.487 (0.630-9.809) | |

| Distant metastasis | ||||

| No | 144 (96.6%) | 137 (95.1%) | 1.00 | p = 0.518 |

| Yes | 5 (3.4%) | 7 (4.9%) | 1.471 (0.456-4.747) | |

| Vascular invasion | ||||

| No | 126 (84.7%) | 112 (77.8%) | 1.00 | p = 0.139 |

| Yes | 23 (15.4%) | 32 (22.2%) | 1.565 (0.865-2.832) | |

| Child-Pugh grade | ||||

| A | 125 (83.9%) | 102 (70.8%) | 1.00 | p = 0.008* |

| B or C | 24 (16.1%) | 42 (29.2%) | 2.145 (1.218-3.776) | |

| HBsAg | ||||

| Negative | 82 (55.0%) | 87 (60.4%) | 1.00 | p = 0.096 |

| Positive | 67 (45.0%) | 57 (39.6%) | 0.762 (0.554-1.049) | |

| Anti-HCV | ||||

| Negative | 80 (53.7%) | 73 (50.7%) | 1.00 | p = 0.647 |

| Positive | 69 (46.3%) | 71 (49.3%) | 0.924 (0.659-1.295) | |

| Liver cirrhosis | ||||

| Negative | 26 (17.4%) | 23 (16.0%) | 1.00 | p = 0.735 |

| Positive | 123 (82.6%) | 121 (84.0%) | 1.112 (0.601-2.056) | |

The ORs with analyzed by their 95% CIs were estimated by logistic regression models.

> T2: multiple tumor more than 5 cm or tumor involving a major branch of the portal or hepatic vein(s)

* p value < 0.05 as statistically significant.

When we investigated associations between MMP-11 gene polymorphisms and serum levels of alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), aspartate transaminase (AST) and alanine transaminase (ALT) in HCC patients [24], we found no significant associations between the levels of these HCC clinical pathologic markers and genotypes of any MMP-11 SNPs (Table 5).

We searched the GTEx database to investigate whether rs738792 was associated with MMP-11 expression. Individuals carrying a genotype with the variant C at rs738792 showed a trend for reduced expression of MMP-11, compared with the wild-type TT homozygous genotypes (p < 0.05; Figure 1).

Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) associated with clinical status and MMP-11 rs28382575 genotypic frequencies in 293 patients with hepatocellular carcinoma.

| Variable | Genotypic frequencies | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TT (N=281) | CT+CC (N=12) | OR (95% CI) | p value | |

| Clinical Stage | ||||

| Stage I/II | 200 (71.2%) | 5 (41.7%) | 1.00 | p = 0.039* |

| Stage III/IV | 81 (28.8%) | 7 (58.3%) | 3.457 (1.066-11.208) | |

| Tumor size | ||||

| ≦ T2 | 201 (71.5%) | 5 (41.7%) | 1.00 | p = 0.036* |

| > T2 | 80 (28.5%) | 7 (58.3%) | 3.517 (1.085-11.407) | |

| Lymph node metastasis | ||||

| No | 274 (97.5%) | 9 (75.0%) | 1.00 | p = 0.001* |

| Yes | 7 (2.5%) | 3 (25.0%) | 13.048 (2.892-58.868) | |

| Distant metastasis | ||||

| No | 269 (95.7%) | 12 (4.3%) | 1.00 | - |

| Yes | 12 (100.0%) | 0 (3.2%) | - | |

| Vascular invasion | ||||

| No | 230 (81.8%) | 8 (66.7%) | 1.00 | p = 0.198 |

| Yes | 51 (18.2%) | 4 (33.3%) | 2.255 (0.654-7.776) | |

| Child-Pugh grade | ||||

| A | 218 (77.6%) | 9 (75.0%) | 1.00 | p = 0.834 |

| B or C | 63 (22.4%) | 3 (25.0%) | 1.153 (0.303-4.389) | |

| HBsAg | ||||

| Negative | 162 (57.7%) | 7 (58.3%) | 1.00 | p = 0.419 |

| Positive | 119 (42.3%) | 5 (41.7%) | 0.692 (0.284-1.688) | |

| Anti-HCV | ||||

| Negative | 147 (52.3%) | 6 (50.0%) | 1.00 | p = 0.930 |

| Positive | 134 (47.7%) | 6 (50.0%) | 1.039 (0.447-2.414) | |

| Liver cirrhosis | ||||

| Negative | 46 (16.4%) | 3 (25.0%) | 1.00 | p = 0.438 |

| Positive | 235 (83.6%) | 9 (75.0%) | 0.587 (0.153-2.252) | |

The ORs with analyzed by their 95% CIs were estimated by logistic regression models.

> T2: multiple tumor more than 5 cm or tumor involving a major branch of the portal or hepatic vein(s)

* p value < 0.05 as statistically significant.

Discussion

Preclinical studies have indicated that MMP-11 mediates metastasis of cancer including MMP-11 expression regulates local or distant invasion in transgenic mice [25]. Furthermore, knockdown of MMP-11 expression in the mouse hepatocarcinoma cell line Hca-F inhibits its metastatic proliferation to lymph nodes [26]. In the breast cancer microenvironment also found MMP-11-positive mononuclear inflammatory cells infiltration and facilitated to form metastases [27]. The role of MMP-11 in the metastatic process, however, might be complex and even dual, probably depending on different spatiotemporal factors [28]. When we examined the influence of the MMP-11 gene upon the metastatic phenotype of HCC, we discovered a significantly higher likelihood of lymph node metastasis among patients carrying the rs28382575 C/T+C/C genotype as compared with T/T carriers. These results suggest that knockdown MMP-11 might be a valuable therapeutic strategy for HCC lymph node metastasis.

Association of MMP-11 genotypic frequencies with HCC laboratory status.

| Characteristic | α-Fetoproteina (ng/mL) | AST (IU/L) | ALT (IU/L) | AST/ALT ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs738791 | ||||

| CC | 922.1 ± 477.2 | 57.01 ± 9.19 | 55.88 ± 8.61 | 1.18 ± 0.03 |

| TC+TT | 1020.9 ± 372.4 | 54.80 ± 4.38 | 52.60 ± 4.33 | 1.23 ± 0.05 |

| p value | 0.870 | 0.823 | 0.733 | 0.382 |

| p valueb | 0.865 | 0.809 | 0.713 | 0.401 |

| rs2267029 | ||||

| TT | 1280.4 ± 442.0 | 60.38 ± 8.47 | 58.11 ± 7.78 | 1.21 ± 0.05 |

| AT+AA | 708.9 ± 386.9 | 50.61 ± 3.50 | 49.48 ± 4.09 | 1.20 ± 0.03 |

| p value | 0.395 | 0.286 | 0.326 | 0.936 |

| p valueb | 0.390 | 0.298 | 0.333 | 0.938 |

| rs738792 | ||||

| TT | 1041.2 ± 407.8 | 61.93 ± 9.11 | 59.64 ± 8.35 | 1.21 ± 0.05 |

| GT+GG | 911.7 ± 432.1 | 49.83 ± 3.27 | 48.64 ± 3.84 | 1.20 ± 0.03 |

| p value | 0.828 | 0.212 | 0.232 | 0.894 |

| p valueb | 0.823 | 0.197 | 0.217 | 0.892 |

| rs28382575 | ||||

| AA | 886.2 ± 282.2 | 56.03 ± 5.00 | 54.40 ± 4.75 | 1.20 ± 0.03 |

| AG+GG | 3077.3 ± 3006.4 | 51.17 ± 10.60 | 46.89 ± 10.36 | 1.21 ± 0.09 |

| p value | 0.473 | 0.680 | 0.513 | 0.944 |

| p valueb | 0.134 | 0.837 | 0.738 | 0.965 |

| rs131451 | ||||

| AA | 1546.8 ± 584.5 | 55.17 ± 7.59 | 56.17 ± 8.62 | 1.17 ± 0.04 |

| AG+GG | 660.2 ± 328.8 | 56.20 ± 6.19 | 52.95 ± 5.27 | 1.22 ± 0.04 |

| p value | 0.187 | 0.918 | 0.750 | 0.375 |

| p valueb | 0.143 | 0.916 | 0.729 | 0.416 |

Mann-Whitney U test was used between two groups.

a Mean ± S.E.

b Adjusted age, sex, drink, HBsAg, and anti-HCV.

* p value < 0.05 as statistically significant

MMP-11 displays a significant eQTL association with the rs738792 genotype in liver tissue (GTEx data set).

In view of the high occurrence rate and lethality of HCC, lowering the incidence and mortality rates present an important challenge. Infection with HBV or HCV, a history of liver cirrhosis, family history of HCC, and alcohol consumption are the dominant etiological factors for HCC in Taiwan [29]. In this study, no between-group differences were observed between the ratios of cigarette smokers/nonsmokers among controls (40.8:59.2, respectively) and HCC patients (41.6:58.4, respectively), whereas a higher proportion of HCC patients consumed alcohol (37.2%) compared with controls (14.5%). This suggests that alcohol consumption is a risk factor for HCC development. Chronic alcohol consumption promotes hepatobiliary tumors by increasing microRNA-122-controlled HIF-1α activity and stemness [30]. This is supported by findings from a swine model of chronic hypercholesterolemia, in which moderate alcohol consumption altered autophagy- and apoptosis-regulated pathways [31]. Interestingly, the findings indicated that a hypercholesterolemic diet supplemented with vodka appeared to induce pro-apoptotic pathways in liver tissue, whereas wine appeared to induce anti-apoptotic signaling. Our data is consistent with clinical evidence showing that alcohol consumption is a risk factor for HCC [32, 33]; we found that HCC patients who consumed alcohol were at higher risk of worsening disease.

Previous research has found no significant difference in the occurrence of oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) amongst individuals with polymorphisms of the MMP-11 gene in rs738791 [18]. In addition, the patients with rs738791 polymorphism and betel nut chewing increased risk for OSCC when compared to subjects with wild-type genes and without a history of betel nut chewing [34]. In this study, we found that the MMP-11 rs738791 polymorphism was associated with HCC risk. These findings suggest that different MMP-11 polymorphisms play different roles in cancer development. This study found that HCC patients with the MMP1 rs738792 polymorphism had a higher risk of developing Child-Pugh B or C grade. Similarly, the MMP-11 rs28382575 polymorphism was also associated with a higher risk of developing stage III/IV disease, large tumors and lymph node metastasis. It is established that MMP-11 expression controls the miR-125a regulated metastasis of HCC [16]. In addition, CD147 regulated HCC invasion and multidrug resistance through MMP-11 upregulation [35]. More research is required to determine whether an association exists among advanced-stage disease, MMP-11 expression levels, and MMP-11 genotype, and clarification is needed in regard to the effects of the MMP-11 genotype on HCC risk.

In conclusion, the current study suggests a potentially clinically significant finding showing that several variants of the MMP-11 gene are associated with the clinical status and susceptibility of HCC. However, we dose not recruited the survival results of HCC. Future research could evaluate the association of HMGB1 polymorphisms with survival of HCC. We found that individuals carrying the CT+TT allele of the MMP-11 SNP rs738791 were at higher risk of HCC than wild-type (C/C) carriers. Genetic variations in the gene encoding MMP-11 may be a significant predictor of early HCC occurrence and a reliable biomarker for disease progression.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from Taiwan's Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST106-2320-B-039-005).

Competing Interests

The authors have declared that no competing interest exists.

References

1. Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2013;63:11-30

2. Blechacz B, Mishra L. Hepatocellular carcinoma biology. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2013;190:1-20

3. Ezzikouri S, Benjelloun S, Pineau P. Human genetic variation and the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma development. Hepatology international. 2013;7:820-31

4. Bosch FX, Ribes J, Cleries R, Diaz M. Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Liver Dis. 2005;9:191-211 v

5. Wu CY, Huang HM, Cho DY. An acute bleeding metastatic spinal tumor from HCC causes an acute onset of cauda equina syndrome. Biomedicine (Taipei). 2015;5:18

6. Shastry BS. SNP alleles in human disease and evolution. Journal of human genetics. 2002;47:561-6

7. Lau HK, Hsieh MJ, Yang SF, Wang HL, Kuo WH, Lee HL. et al. Association between Interleukin-18 Polymorphisms and Hepatocellular Carcinoma Occurrence and Clinical Progression. International journal of medical sciences. 2016;13:556-61

8. Wang B, Yeh CB, Lein MY, Su CM, Yang SF, Liu YF. et al. Effects of HMGB1 Polymorphisms on the Susceptibility and Progression of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. International journal of medical sciences. 2016;13:304-9

9. Wang B, Chou YE, Lien MY, Su CM, Yang SF, Tang CH. Impacts of CCL4 gene polymorphisms on hepatocellular carcinoma susceptibility and development. International journal of medical sciences. 2017;14:880-4

10. Lopez-Soto A, Gonzalez S, Smyth MJ, Galluzzi L. Control of Metastasis by NK Cells. Cancer cell. 2017;32:135-54

11. John A, Tuszynski G. The role of matrix metalloproteinases in tumor angiogenesis and tumor metastasis. Pathology oncology research: POR. 2001;7:14-23

12. Yang HK, Jeong KC, Kim YK, Jung ST. Role of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) 2 and MMP-9 in soft tissue sarcoma. Clinics in orthopedic surgery. 2014;6:443-54

13. Lefebvre O, Regnier C, Chenard MP, Wendling C, Chambon P, Basset P. et al. Developmental expression of mouse stromelysin-3 mRNA. Development. 1995;121:947-55

14. Fiorentino M, Fu L, Shi YB. Mutational analysis of the cleavage of the cancer-associated laminin receptor by stromelysin-3 reveals the contribution of flanking sequences to site recognition and cleavage efficiency. International journal of molecular medicine. 2009;23:389-97

15. Rouyer N, Wolf C, Chenard MP, Rio MC, Chambon P, Bellocq JP. et al. Stromelysin-3 gene expression in human cancer: an overview. Invasion & metastasis. 1994;14:269-75

16. Bi Q, Tang S, Xia L, Du R, Fan R, Gao L. et al. Ectopic expression of MiR-125a inhibits the proliferation and metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma by targeting MMP11 and VEGF. PloS one. 2012;7:e40169

17. Koleck TA, Bender CM, Clark BZ, Ryan CM, Ghotkar P, Brufsky A. et al. An exploratory study of host polymorphisms in genes that clinically characterize breast cancer tumors and pretreatment cognitive performance in breast cancer survivors. Breast cancer. 2017;9:95-110

18. Lin CW, Yang SF, Chuang CY, Lin HP, Hsin CH. Association of matrix metalloproteinase-11 polymorphisms with susceptibility and clinicopathologic characteristics for oral squamous cell carcinoma. Head & neck. 2015;37:1425-31

19. Vauthey JN, Lauwers GY, Esnaola NF, Do KA, Belghiti J, Mirza N. et al. Simplified staging for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1527-36

20. Schache M, Baird PN. Assessment of the association of matrix metalloproteinases with myopia, refractive error and ocular biometric measures in an Australian cohort. PloS one. 2012;7:e47181

21. Li TC, Li CI, Liao LN, Liu CS, Yang CW, Lin CH. et al. Associations of EDNRA and EDN1 polymorphisms with carotid intima media thickness through interactions with gender, regular exercise, and obesity in subjects in Taiwan: Taichung Community Health Study (TCHS). Biomedicine (Taipei). 2015;5:8

22. Consortium GT. The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project. Nature genetics. 2013;45:580-5

23. Wang CQ, Tang CH, Wang Y, Jin L, Wang Q, Li X. et al. FSCN1 gene polymorphisms: biomarkers for the development and progression of breast cancer. Scientific reports. 2017;7:15887

24. Simpson HN, McGuire BM. Screening and detection of hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Liver Dis. 2015;19:295-307

25. Andarawewa KL, Boulay A, Masson R, Mathelin C, Stoll I, Tomasetto C. et al. Dual stromelysin-3 function during natural mouse mammary tumor virus-ras tumor progression. Cancer research. 2003;63:5844-9

26. Jia L, Wang S, Cao J, Zhou H, Wei W, Zhang J. siRNA targeted against matrix metalloproteinase 11 inhibits the metastatic capability of murine hepatocarcinoma cell Hca-F to lymph nodes. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology. 2007;39:2049-62

27. Eiro N, Fernandez-Garcia B, Gonzalez LO, Vizoso FJ. Cytokines related to MMP-11 expression by inflammatory cells and breast cancer metastasis. Oncoimmunology. 2013;2:e24010

28. Brasse D, Mathelin C, Leroux K, Chenard MP, Blaise S, Stoll I. et al. Matrix metalloproteinase 11/stromelysin-3 exerts both activator and repressor functions during the hematogenous metastatic process in mice. International journal of cancer. 2010;127:1347-55

29. Chen TH, Chen CJ, Yen MF, Lu SN, Sun CA, Huang GT. et al. Ultrasound screening and risk factors for death from hepatocellular carcinoma in a high risk group in Taiwan. International journal of cancer. 2002;98:257-61

30. Ambade A, Satishchandran A, Szabo G. Alcoholic hepatitis accelerates early hepatobiliary cancer by increasing stemness and miR-122-mediated HIF-1alpha activation. Scientific reports. 2016;6:21340

31. Potz BA, Lawandy IJ, Clements RT, Sellke FW. Alcohol modulates autophagy and apoptosis in pig liver tissue. The Journal of surgical research. 2016;203:154-62

32. Yang MD, Hsu CM, Chang WS, Yueh TC, Lai YL, Chuang CL. et al. Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha Genotypes Are Associated with Hepatocellular Carcinoma Risk in Taiwanese Males, Smokers and Alcohol Drinkers. Anticancer Res. 2015;35:5417-23

33. Urata Y, Yamasaki T, Saeki I, Iwai S, Kitahara M, Sawai Y. et al. Clinical characteristics and prognosis of non-B non-C hepatocellular carcinoma patients with modest alcohol consumption. Hepatol Res. 2015

34. Wang C, Yan Q, Hu M, Qin D, Feng Z. Effect of AURKA Gene Expression Knockdown on Angiogenesis and Tumorigenesis of Human Ovarian Cancer Cell Lines. Targeted oncology. 2016;11:771-81

35. Jia L, Xu H, Zhao Y, Jiang L, Yu J, Zhang J. Expression of CD147 mediates tumor cells invasion and multidrug resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer investigation. 2008;26:977-83

Author contact

![]() Corresponding authors: Chih-Hsin Tang, PhD. E-mail: chtangcmu.edu.tw, Department of Pharmacology, School of Medicine, China Medical University, Taichung, Taiwan and Shun-Fa Yang, PhD. E-mail: ysfedu.tw, Institute of Medicine, Chung Shan Medical University, Taichung, Taiwan

Corresponding authors: Chih-Hsin Tang, PhD. E-mail: chtangcmu.edu.tw, Department of Pharmacology, School of Medicine, China Medical University, Taichung, Taiwan and Shun-Fa Yang, PhD. E-mail: ysfedu.tw, Institute of Medicine, Chung Shan Medical University, Taichung, Taiwan

Global reach, higher impact

Global reach, higher impact