Impact Factor

ISSN: 1449-1907

Int J Med Sci 2013; 10(5):641-646. doi:10.7150/ijms.5649 This issue Cite

Research Paper

Clinical and Virological Characteristics of Chronic Hepatitis B Patients with Hepatic Steatosis

Research and Therapy Center for Liver Disease, the Affiliated Dongnan Hospital of Xiamen University, Zhangzhou 363000, Fujian, China.

Received 2012-12-4; Accepted 2013-3-13; Published 2013-3-25

Abstract

Objective: This study aimed to explore clinical and virological characteristics of chronic hepatitis B (CHB) patients with hepatic steatosis in order to provide a theoretical basis for the prevention and control of hepatic steatosis.

Methods: A total of 360 CHB inpatients were recruited from Affiliated Dongnan Hospital of Xiamen University and divided into hepatic steatosis group and non- hepatic steatosis group. The body mass index (BMI), waist-to-hip ratio (WHR), fasting blood glucose (FBG), triglyceride (TG), total cholesterol (TC), aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT), hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg), hepatitis B virus DNA (HBV DNA) and hepatic histological changes were detected and compared between the two groups. The association of these factors with hepatic steatosis was evaluated in CHB patients.

Results: BMI, FPG, TG, TC, GGT, AST and HBV DNA showed statistically significant differences between two groups (P<0.01). The patients with hepatic steatosis had markedly higher BMI, FBG, TG and TC than those without steatosis did. No significant differences were found in ALT and HBeAg between two groups (P>0.05). In male patients, there was marked difference in the WHR between two groups (P < 0.01), which was not found in female patients (P > 0.05). The severity of hepatic steatosis increased in patients with hepatic steatosis, compared to those without steatosis (P < 0. 01), but the severities of inflammation and fibrosis in the non-hepatic steatosis group were dramatically higher than those in the hepatic steatosis group (P < 0. 01).

Conclusions: BMI, WHR, FBG, TG and TC appeared to be influencing factors of CHB combined with hepatic steatosis. Hepatic steatosis in CHB patients was closely related to changes in anthropometric indices and metabolic factors but not HBV. It is necessary to improve these factors to effectively prevent hepatic steatosis in CHB patients.

Keywords: Chronic hepatitis B, Hepatic steatosis, anthropometric index, Metabolic factor.

Introduction

The incidences of hyperlipidemia, obesity and diabetes mellitus increase significantly over years due to change in lifestyle, high-fat and high-sugar diet and lack of physical exercise. Correspondingly, the prevalence of hepatic steatosis is on the rise, being the second commonest liver disease in developed countries. Hepatic steatosis is associated with hyperlipidemia, hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, cardio-cerebrovascular diseases and some malignant tumors [1]. At the moment, hepatic steatosis ranks among the second commonest liver disease around the world secondary only to viral hepatitis, which imposes a large burden on human health. It is well known that hepatic steatosis plays an important role in hepatic inflammatory necrosis and fibrosis development in patients with chronic hepatitis C (CHC), and both the metabolic status and hepatitis C virus (HCV) are involved in the pathogenesis of hepatic steatosis [4]. Hepatic steatosis is frequently found in chronic hepatitis B (CHB) [5], a common epidemic disease in China. However, factors affecting the development of hepatic steatosis in CHB patients remain obscure despite coexisting of CHB and hepatic steatosis is frequently observed in clinical practice [6]. This study compared the clinical features among CHB patients with and without hepatic steatosis, so as to explore the factors affecting the development of hepatic steatosis in CHB patients and to provide evidence for clinical prevention and treatment of these conditions.

Material and methods

Patients

A total of 291 CHB inpatients were recruited from the Affiliated Dongnan Hospital of Xiamen University between January 2008 and June 2011. CHB was diagnosed on the basis of clinical presentations and pathological features according to the “Guidelines for Prevention and Treatment of Chronic Hepatitis B (2010 version)” [7]. Infection of hepatitis A virus (HAV), HCV, hepatitis D virus (HDV) and hepatitis E virus (HEV), drug-induced hepatitis, alcoholic hepatitis and autoimmune hepatitis were ruled out before study. These patients were divided into two groups according to the presence of hepatic steatosis. Among all participants, 132 were diagnosed with hepatic steatosis (120 men and 12 women, age: 10-63 years [37.05 ± 9.55 years]) and hepatic steatosis was not observed in remaining 159 patients (138 men and 21 women, age: 19-65 years, [40.38 ± 16.61 years]). This study was approved by the Clinical Ethics Committee of Affiliated Dongnan Hospital of Xiamen University, and informed consent was obtained from all patients before study.

Anthropometry

The height, weight, waist and hip circumference were measured in all patients. Waist circumference was measured using a steel measuring tape, with measurements made halfway between the lower border of the ribs and the anterior superior iliac spine in a horizontal plane. Hip circumference was measured at the level of the greater femoral trochanter. All the subjects were clothed as lightly as possible, barefooted in a standing position, and examined by two well-trained physicians. Body mass index (BMI) and waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) were calculated with following equations: BMI = weight (kg)/height2(m2); WHR = waist circumference (cm)/hip circumference (cm).

Serum assays

Subjects were fasted for 12 h and 5 ml of venous blood was collected in the morning. The levels of glucose (FBG), triglyceride (TG), total cholesterol (TC), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and γ-glutamyltransferase (GGT) were determined.

Serum markers of HBV

HBV markers were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) with a commercially-available kit (Livzon Group Reagent Factory, Guangdong, China) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Detection of HBV DNA

HBV DNA level was determined by quantitative real-time fluorescence polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) using a AG-9600 Thermal Station and a AG-9600 Amplisensor Minilyzer (Biotronic, USA). The fluorescent reagent and the standard HBV DNA were provided by the same company. Asymmetric primer 1 was 5′-TGTCTCGTGTTACAGGCGGGGT-3', asymmetric primer 2 was 5′-GAGGCATAGCAGCAGGAGAAGAG-3', and fluorescent primer was 5′-TCGCTGGAAGTGTCTGCGGCGT-3'. One copy was defined as 3.2 kb HBV DNA in 1 ml of serum, and data were expressed as N = 10 × copies/ml.

Diagnostic criteria

According to the BMI criteria for Asians developed by the Regional Office for the Western Pacific Region of World Health Organization (WHO) (2000) [8], normal weight, overweight and obesity were defined as BMI= 18.5-23.0 kg/m2, 23.0-25.0 kg/m2 and ≥ 25.0 kg/m2, respectively. Central obesity was determined by WHR ≥ 0.9 (male) or ≥ 0.8 (female). Hyperglycemia was diagnosed when the FBG was ≥ 5.6 mmol/L according to the diagnostic criteria of diabetes mellitus by WHO (1999) [9] and the recommended criteria of diabetes mellitus by American Diabetes Association (ADA) (2003) [10]. Hypertriglyceridemia and hypercholesterolemia were diagnosed when TG was ≥ 1.7 mmol/L and TC was ≥ 5.2 mmol/L, respectively, according to the Guidelines on Prevention and Treatment of Blood Lipid Abnormality in Chinese Adults [11]. HBV DNA of ≥ 103 copies/ml was considered positive for virus replication. Hepatic steatosis was graded as: F0 (no significant lipid droplets in hepatocytes), F1 (< 30% hepatocytes with microvesicular steatosis), F2 (30~50% hepatocytes involved), F3 (50~75% hepatocytes involved) and F4 (>75% hepatocytes involved) [12].

Hepatic histology

Liver biopsy was performed to obtain the specimens under the ultrasound guidance within 1 week after admission, using a needle by which a negative pressure (suction) was applied. Each specimen was longer than 2 cm and had more than 10 portal areas. Specimens were immediately fixed in 4% formaldehyde, dehydrated, embedded, sliced, and examined after hematoxylin-eosin staining, Masson's trichrome staining and reticular fiber staining. All the sections were blindly and independently assessed by 2 experienced pathologists [13].

Statistical analysis

A case-control study was conducted. Variables with normal distribution were compared using rank sum test. Quantitative data were expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD). Where appropriate, comparisons were performed using a paired t test or a Mann-Whitney U test. Qualitative data were presented as rate and compared with Chi-square test. A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was done with SPSS version 13.0 for Windows.

Results

Comparison of genders, ages and anthropometric indices

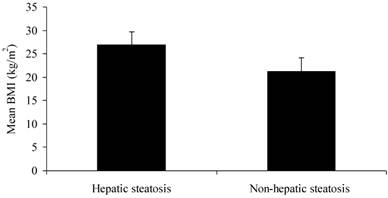

There were no significant differences in gender or age between two groups (P > 0.05). The CHB patients with hepatic steatosis had significantly higher BMI (26.89 ± 2.78 kg/m2) than those without steatosis did (21.17 ± 2.96 kg/m2) (Figure 1; P < 0.01). The WHR of male patients with steatosis (0.93 ± 0.05) was markedly higher than those without steatosis did (0.87 ± 0.06) (P < 0.01). However, the WHR of female patients was comparable between two groups (P > 0.05) (Table 1).

BMI of CHB patients with and without hepatic steatosis

Gender, age and anthropometric indices of CHB patients with and without hepatic steatosis.

| Hepatic steatosis group | Non-hepatic steatosis group | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 132 | 159 | — |

| Gender | 0.270 | ||

| Male (n, %) | 120 (90.91%) | 138 (86.79%) | |

| Female (n, %) | 12 (9.09%) | 21 (13.21%) | |

| Age (yr) | 37.05±9.55 | 40.38±16.61 | 0.220 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.89±2.78 | 21.17±2.96 | 0.000 |

| WHR | |||

| Male | 0.93±0.05 | 0.87±0.06 | 0.000 |

| Female | 0.88±0.06 | 0.87±0.06 | 0.711 |

Serum biochemical parameters

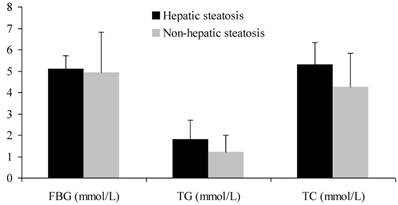

CHB patients with steatosis had significantly higher levels of FBG, TG and TC than those without steatosis did (P < 0.01) (Figure 2). On the other hand, GGT and AST were markedly higher in patients without steatosis than in those with steatosis (P < 0.01). There was no significant difference in ALT between two groups (P > 0.05) (Table 2).

FBG, TG and TC of CHB patients with and without hepatic steatosis

Serum biochemical parameters of CHB patients with and without hepatic steatosis.

| Hepatic steatosis group | Non-hepatic steatosis group | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| FBG (mmol/L) | 5.11±0.62 | 4.94±1.89 | 0.000 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.81±0.89 | 1.21±0.79 | 0.000 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 5.29±1.05 | 4.25±1.58 | 0.000 |

| GGT (IU/L) | 65.04±53.89 | 146.48±200.39 | 0.009 |

| AST (IU/L) | 65.60±71.52 | 165.35±180.57 | 0.003 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 135.39±151.99 | 273.99±336. 88 | 0.385 |

Virological parameters

There was no significant difference in positive rate of HBeAg between two groups (P > 0.05), while the positive rate of HBV DNA in non-hepatic steatosis group was significantly higher (P < 0.01). The positive rates of HBeAg and HBV DNA in patients with steatosis were 43.18% and 70.45%, respectively, while they were 49.06% and 84.91%, respectively, in patients without steatosis (Table 3).

Virological parameters of CHB patients with and without hepatic steatosis.

| Hepatic steatosis group (N=132) | Non-hepatic steatosis group (N=159) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HBeAg | 0.317 | ||

| + | 57 (43.18%) | 78 (49.06%) | |

| — | 75 (56.82%) | 81 (50.94%) | |

| HBV DNA | 0.003 | ||

| + | 93 (70.45%) | 135 (84.91%) | |

| — | 39 (29.55%) | 24 (15.09%) |

Pathological findings

Patients with hepatic steatosis had more severe fatty degeneration than those without hepatic steatosis did (P < 0. 01). However, the prevalence of hepatic inflammation and fibrosis were markedly higher in patients without steatosis when compared with those with steatosis (P < 0. 01). Histological features of CHB patients with and without hepatic steatosis are summarized in Table 4.

Histological features of CHB patients with and without hepatic steatosis.

| Hepatic steatosis group (N=132) | Non-hepatic steatosis group (N=159) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Steatosis | 0.000 | ||

| F0 | 0 | 159 | |

| F1 | 36 | 0 | |

| F2 | 48 | 0 | |

| F3 | 43 | 0 | |

| F4 | 5 | 0 | |

| Inflammation activity | 0.000 | ||

| G0 | 78 | 0 | |

| G1 | 29 | 18 | |

| G2 | 25 | 98 | |

| G3 | 0 | 43 | |

| Fibrosis stage | 0.000 | ||

| S1 | 118 | 35 | |

| S2 | 13 | 97 | |

| S3 | 0 | 22 | |

| S4 | 1 | 5 | |

Discussion

The incidence of CHB is decreasing as a result of effective implementation of hepatitis B vaccination, and the proportion of HBV carriers also significantly declines due to proper use of antiviral agents [14]. The prevalence of HBsAg positive patients in China also decreases, although it is still as high as 7.18% [7]. In clinical practice, hepatic steatosis is frequently found in CHB patients [6] with a reported incidence of 18%-27% [15, 16]. With the improvement of living standard and change in lifestyle in recent years, the distributions of BMI, WHR and WC also significantly alter. The BMI, WHR and WC are continuously increasing in both developed and developing countries. The numbers of overweight and obese subjects are 14.6 billion and 500 million, respectively, around the world [17]. The prevalence of hepatic steatosis in CHB patients tends to increase over years, and patients with these conditions may develop cirrhosis or even hepatocarcinoma [2]. Hepatic steatosis can be induced by excessive alcohol intake, drug abuse, nutrition imbalance and metabolic diseases and is generally associated with hyperlipidemia, hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, cardio-cerebrovascular diseases and some malignant tumors, exerting important impacts on human health [18]. CHB patients usually have different lifestyles and diet habits from healthy people because of lack of exercise and improvement in appetite during recovery period. Therefore, to determine factors influencing the development of hepatic steatosis in CHB patients may help us in the prevention and treatment of these conditions. It is also crucial for screening and confirming these influencing factors of these diseases so that we can timely prevent and early diagnose steatosis in CHB patients.

This was a case-control study on CHB patients with and without hepatic steatosis which was confirmed by clinical and pathological features. There were no significant differences in gender and age between two groups. Our results showed that the BMI of steatosis patients was significantly higher than that of non-steatosis patients. The mean WHR of male patients differed between two group, which was not observed in female patients, probably because of different distribution patterns of body fat between males and females [19]. It is well known that WHR is one of most important anthropometric indices that can predict the occurrence of simple fatty liver [20]. The present study showed that CHB patients with steatosis had higher BMI and WHR than those without steatosis did. CHB patients are more likely to develop hepatic steatosis as their BMI and WHR increase, suggesting that increased BMI and WHR may promote hepatic fat deposition in CHB patients. Thus, to control the increases in BMI and WHR is an effective way to prevent hepatic steatosis in CHB patients. Moreover, steatosis patients had higher levels of FBG, TG and TC than non-steatosis patients, indicating that inflammation in the liver is related to disordered metabolism of blood glucose and lipid (especially hypertriglyceridemia). It is important to closely monitor the BMI, WHR, blood glucose and lipid and to treat hypertriglyceridemia in CHB patients which may prevent the occurrence of hepatic steatosis. In addition, the levels of ALT, AST and GGT were significantly higher in steatosis patients than in non-steatosis patients. It is possible that CHB patients with hepatic steatosis develop metabolic disorders, according to the increased BMI and WHR. The metabolic disorders may interact with CHB, further causing damage to liver function [22]. Our results indicated that, in order to prevent hepatic steatosis in CHB patients, it is beneficial to periodically monitor BMI and WHR, to properly control the blood glucose and lipid, as well as to educate these patients about healthy lifestyle, scientific dieting and physical exercise.

A large body of evidence has demonstrated that HCV combined with hepatic steatosis is associated with type 3 HCV gene, which accounts for 80% of all HCV infections [4]. The mechanism of type 3 HCV infection lies in that the core protein of HCV inhibits the activity of microsomal triglyceride transfer protein and interferes with the assembly and secretion of very low density lipoprotein [21]. In the present study, the positive rates of HBeAg and HBV DNA were compared between patients with and without steatosis, and results showed that there was no significant difference in the positive rate of HBeAg between two groups, while the positive rate of HBV DNA was significantly different. These results suggest that liver injury in CHB patients without hepatic steatosis is related to HBV. The positive rate of HBV DNA in patients with steatosis was lower than that in patients without steatosis, which means that HBV is not directly related to the hepatic steatosis in CHB patients. It was reported that the HBV DNA load was significantly lower in CHB patients with hepatic steatosis than in those without hepatic steatosis and that hepatic steatosis in CHB patients was not related to HBV infection [23]. Previous clinical studies revealed that both CHB patients with hepatic steatosis and hepatic steatosis patients had hyperlipidemia and obesity, suggesting that the occurrence and development of hepatic steatosis in CHB patients are closely associated with metabolic factors [24], which is consistent with our results.

Pathological examination in the present study showed that the prevalence of hepatic inflammation and fibrosis was significantly higher in patients without steatosis, suggesting that, when HBV infection and hepatic steatosis coexist, hepatic steatosis may not affect the severity of hepatic inflammation and fibrosis of patients with HBV infection, but these results remain to be confirmed in epidemiologic studies and clinical cohort studies.

Early diagnosis of hepatic steatosis in CHB patients seems to be difficult. The pathological features are the golden standard for the diagnosis of hepatic steatosis in CHB patients, but it is impossible for wide application in clinical practice. In addition, the noninvasive method of fibroscan for diagnosis of hepatic steatosis is currently in the exploratory stage [25, 26]. Our findings showed that anthropometric indices and metabolic factors were related to hepatic steatosis in CHB patients, and BMI, WHR, FBG, TG and TC, but not HBV, were influencing factors of steatosis. Therefore, to monitor anthropometric indices (especially BMI and WHR) and to measure biochemical parameters (such as FBG, TG and TC) are helpful for early diagnosis of hepatic steatosis, evaluation of antiviral treatment and improvement of prognosis in CHB patients. There are some limitations in this study, such as lack of evaluation of antiviral treatment. It remains controversial whether hepatic steatosis influences the efficacy of antiviral therapy. Clinical investigations showed that treatment with polyethylene glycol interferon in CHB patients with hepatic steatosis for 48 weeks had no influence on the virological response but altered the biochemical response [27]. However, another study showed that hepatic steatosis was significantly associated with Entecavir treatment failure [28]. Thus, the antiviral treatment in CHB patient with hepatic steatosis needs to be further assessed to determine whether the hepatic steatosis affects the efficacy of antiviral treatment.

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by the Zhangzhou Technology Project (Z04094) and Tianqing Hepatic Disease Fund of Chinese Foundation of Hepatitis Prevention and Control (TQGB2011018).

Competing Interests

The authors have declared that no competing interest exists.

References

1. Anand SS, Yusuf S. Stemming the global tsunami of cardiovascular disease. Lancet. 2011;377:529-532

2. Fan JG, Farrell GC. Epidemiology of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in China. J Hepatol. 2009;50:204-210

3. Bjornsson E, Angulo P. Hepatitis C and steatosis. Arch Med Res. 2007;38:621-627

4. Bondini S, Younossi ZM. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and hepatitis C infection. Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol. 2006;52:135-143

5. [Fan JG, Chitturi S. Hepatitis B and fatty liver: causal or coincidental? J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:779-782

6. Zheng RD, Xu CR, Jiang L. et al. Predictors of hepatic steatosis in HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B patients and their diagnostic values in hepatic fibrosis. Int J Med Sci. 2010;7:272-277

7. Chinese Society of Hepatology, Chinese Society of Infectious Diseases. The guideline of prevention and treatment for chronic hepatitis B (2010 version). Chin Prev Med. 2011;12:1-15

8. International Diabetes Institute. The Asia-Pacific Perspective: Redefining Obesity and Its Treatment. Melbourne: Health Communications Australia. 2000

9. World Health Organization. Diagnosis, and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications. Report of a WHO consultation. Part I: Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Geneva: World Health Organization. 1999

10. The Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Follow-up report on the diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:3160-3167

11. Kleiner DE, Brunt EM. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: pathologic patterns and biopsy evaluation in clinical research. Semin Liver Dis. 2012;32(1):3-13

12. The joint committee for guideline of prevention and treatment of lipid abnormality in Chinese adults. The guideline of prevention and treatment of lipid abnormality in Chinese adults. Chin J Cardiol. 2007;35:390-413

13. Zheng RD, Lu LG, Meng JR. et al. A clinical and pathological study of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Chin J Hepatol. 2006;14:449-452

14. Romano' L, Paladini S, Van Damme P. et al. The worldwide impact of vaccination on the control and protection of viral hepatitis B. Dig Liver Dis. 2011;43:S2-7

15. Thomopoulos KC, Arvaniti V, Tsamantas AC. et al. Prevalence of liver steatos is in patients with chronic hepatitis B: a study of associated factors and of relationship with fibrosis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;18:233-237

16. Gordon A, Mclean CA, Pedersen JS. et al. Hepatic steatosis in chronic hepatitis B and C: predictors, distribution and effect on fibrosis. J Hepatol. 2005;43:38-44

17. Finucane MM, Stevens GA, Cowan MJ. et al. National, regional and global trends in body-mass index since 1980: systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with 960 country-years and 9.1 million participants. Lancet. 2011;377:557-567

18. Onyekwere CA, Ogbera AO, Balogun BO. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and the metabolic syndrome in an urban hospital serving an African community. Ann Hepatol. 2011;10:119-124

19. Reid AE. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:710-723

20. Jiang L, Chen XW, Zheng RD. et al. Waist-to-hip ratio is a superior predictor for non-alcoholic simple fatty liver. Chin J Hepatol. 2010;18:859-861

21. Fan JG, Guan YF. Strengthen researches on hyperlidaemia and fatty liver with Chinese characteristics. Chin J Hepatol. 2011;19:641-642

22. Perlemuter G, Sabile A, Letteton P. et al. Hepatitis C virus core protein inhibits microsomal triglyceride transferprotein activity and very low density lipoprotein secretion: a model of viral-related steatosis. FASEB J. 2002;16:185-194

23. Rastogi A, Sakhuja P, Kumar A. et al. Steatosis in chronic hepatitis B: prevalence and correlation with biochemical, histologic, viral, and metabolic parameters. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2011;54(3):454-9

24. Altlparmak E, Koklu S, Yalinkilic M. et al. Viral and host causes of fatty liver in chronic hepatitis B. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:3056-3059

25. Shi JP, Xun YH, Su YX. et al. Metabolic syndrome and severity of fibrosis in patients with chronic viral hepatitis B infection or non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Afr J Microbiol Res. 2011;5:481-484

26. Myers RP, Pollett A, Kirsch R. et al. Controlled Attenuation Parameter (CAP): a noninvasive method for the detection of hepatic steatosis based on transient elastography. Liver Int. 2012;32:902-910

27. Shi JP, Lu L, Qian JC, Ang J. et al. Impact of liver steatosis on antiviral effects of pegylated interferon-alpha in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi. 2012;20:285-288

28. Jin X, Chen YP, Yang YD. et al. Association between hepatic steatosis and entecavir treatment failure in Chinese patients with chronic hepatitis B. PLoS One. 2012;7:e34198

Author contact

![]() Corresponding author: Yan-hui Lu, Email: proflunet; zhengruidanedu.cn.

Corresponding author: Yan-hui Lu, Email: proflunet; zhengruidanedu.cn.

Global reach, higher impact

Global reach, higher impact