Impact Factor

ISSN: 1449-1907

Int J Med Sci 2013; 10(4):427-433. doi:10.7150/ijms.5472 This issue Cite

Research Paper

Efficacy of Entecavir Treatment for up to 5 Years in Nucleos(t)ide-Naïve Chronic Hepatitis B Patients in Real Life

1. Department of Infectious Diseases, The Third Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou 510630, China;

2. Department of Pathology, Medical College of Jinan University, Guangzhou 510632, China.

Received 2012-10-31; Accepted 2013-2-22; Published 2013-3-1

Abstract

Objective: To analyze the efficacy and safety of entecavir (ETV) treatment for up to 5 years in nucleos(t)ide-naïve chronic hepatitis B patients in real life.

Methods: We retrospectively analyzed 230 nucleos(t)ide naïve chronic hepatitis B patients who received ETV 0.5 mg/day monotherapy for at least 3 months, of whom 113 were HBeAg positive and 117 were HBeAg negative. The primary endpoints was cumulative probability of achieving a virological response (undetectable serum HBV DNA, <100IU/mL). Secondary endpoints were rates of ALT normalization (ALT < upper limit of normal), HBeAg seroconversion, resistance, and safety.

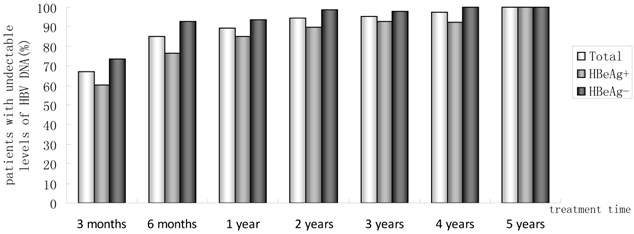

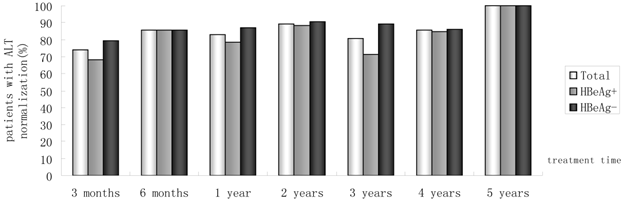

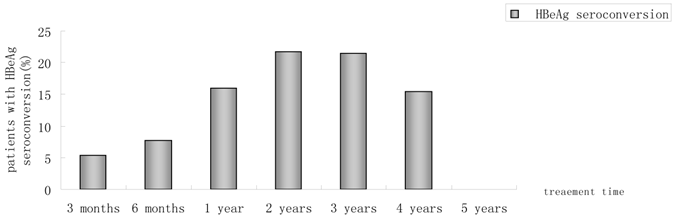

Results: The median follow-up duration was 27.5 months (3-73 months) and mean age was 42 years. With 230, 214, 180, 142, 88, 42 and 11 patients followed-up for at least 3 months,6 months, 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 years, respectively. In all, Incremental increases were observed in the rates of undetectable HBV DNA. 67.0%, 85.0%, 89.4%, 94.4%, 95.5%, 97.6%, 100% had undetectable HBV DNA at month 3, month 6, 1 year, 2 years, 3 years, 4 years and 5 years. Proportions of patients achieving normal ALT were 73.9%, 85.5%, 82.8%, 89.4%, 80.7%, 85.7%, 100%, respectively. The rate of HBeAg seroconversion reached 21.4% and 15.4% at year2, 3, respectively. One patient achieved HBsAg seroclearance after 1 year, and achieved anti-HBs seroconversion at year 3. Of 180 patients, HBV DNA was detectable (partial virological response, PVR) in 19 patients at year 1 of follow-up, twelve of 14 (85.7%) patients with PVR need more than 1 year of continuous ETV therapy to achieved VR. At baseline, no ETV-resistance was detected in 25 ETV-naïve patients. One patient developed ETV-resistance mutations due to noncompliance. No serious adverse event was reported.

Conclusion: Long-term ETV treatment of nucleos(t)ide-naïve was effective and safe in real life. Adjustment of ETV monotherapy in nucleos(t)ide-naïve patients with a partial virological response at 1 year may be unnecessary.

Keywords: Hepatitis B, Chronic, Entecavir, Nucleos(t)ide analogues, Resistance

Introduction

As stated in the Asian-Pacific consensus statement on the management of chronic hepatitis B, the goal of therapy for hepatitis B is to suppress HBV replication in a sustained manner and prevent progression of the disease to cirrhosis, decompensated cirrhosis, end-stage liver disease, HCC, and its complications, aiming to improve the quality of life and survival. Antiviral therapy is critical to reduce the HBV DNA to a level as low as possible [1].

Entecavir (ETV) is a cyclopentyl guanosine analogue and a potent and selective inhibitor of HBV replication in vitro. The rates of histologic improvement, virologic response, and normalization of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels were significantly higher with ETV than with lamivudine (LAM) and adefovir dipivoxil (ADV) [2,3]. Chang et al compared the efficiency of ETV and LAM in patients with HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B in a multi-center, random, double-blind trial. More patients in the entecavir group than in the LAM group had undetectable serum HBV DNA levels (67% vs. 36%, p<0.001) and normalization of ALT levels (68% vs. 60 %, p=0.02) at 48 weeks [2].The results of up to 2 years of ETV vs LAM therapy in nucleoside-naïve HBeAg-positive patients with chronic hepatitis B shows that 156 (64%) had serum HBV DNA <300 copies/mL at week 48, increasing to 180 (74%) at end of dosing. In year 2, 161 (66%) of patients treated with ETV had ALT normalization at 48 weeks, and at the end of dosing in year 2, this number had increased to 183 (79%) [4]. Chang et al presented the results after up to 5 years (240 weeks) of continuous entecavir therapy. At year 5, 94% (88/94) had HBV DNA <300 copies/mL and 80% (78/98) had normal ALT levels. In addition to patients who achieved serologic responses during study ETV-022, 23% (33/141) achieved HBeAg seroconversion and 1.4% (2/145) lost HBsAg [5]. After 96weeks in ETV-060 (120-148 weeks total ETV treatment time), 88% (127/144) of patients had HBV DNA <400 copies/mL. The 3-year cumulative probability of resistance was 1.2% for the 0.5 mg subset [6]. The above results indicate that ETV treatment for nucleoside-naïve patients resulted in high rates of virological, biochemical, and histological response, with minimal resistance.

Nucleos(t)ide analogues (NAs), including ETV and tenofovir (TDF), are potent HBV inhibitors and they have a high barrier to resistance. Thus they can be confidently used as first-line monotherapies. However, there are increasing number of patients who experienced treatment failure to different NA treatment regimens. They discontinued therapy or change treatment plan because of inadequate response, noncompliance, or financial barriers, which poses a growing problem in daily clinical practice. Compared to strictly-controlled clinical trials, however, efficacy and safety of ETV is often difficult to assess due to poor patient compliance and adherence in real-life. That is why we meant to conduct this research in order to provide objective real-life data for clinical use of ETV. In addition, early detection of patients with partial virological response (PVR) and appropriate intervention for achieving sustained viral suppression have been emphasised. It has been clearly demonstrated that patients who show PVR to LAM or telbivudine (LdT) are at high risk for developing resistance to antiviral therapy [7-8]. However, ten to 33% of patients on ETV monotherapy for 48 weeks showed a PVR [9]. It is thus unclear whether treatment adaptation is necessary for naive patients treated with the more potent drug ETV in real life. Therefore, the aims of this retrospective study were to (1) evaluate the long-term efficiency of ETV treatment in NA-naïve chronic hepatitis B patients in real life, (2) assess the efficacy of continuous ETV therapy in some ETV -naïve patients who failed to achieve virological response at 1 year.

Patients and methods

Study population

This retrospective study collected consecutive patients from the Department of Infectious Diseases, The Third Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University between June 2006 and September 2012. All chronic hepatitis B patients were diagnosed with the Guideline of Prevention and Treatment for Chronic Hepatitis B (2010 Version)[10] and were treated with ETV 0.5 mg/day monotherapy. Further eligibility criteria were: age 18-65; have detectable HBsAg for 6 Months; HBV DNA>2000IU/mL; ALT>2 upper limit of normal (ULN); duration of ETV monotherapy for at least 3 months. Patients were excluded from studies if they had HIV and other hepatitis viruses infections, or evidence of liver decompensation (alcoholic Hepatitis, autoimmune hepatitis, and drug-induced liver disease). Pregnant and nursing women were also excluded. The study protocol conformed to the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Third Affiliated Hospital Ethical Committee. Informed consent was obtained from each patient enrolled in the study. Among 246 patients treated with ETV 0.5 mg/day, 16 were excluded because of duration of ETV monotherapy less than 3 months (n=13), incomplete data at base line (n=3). A total of 230 patients were eligible for this analysis.

Study design

Subjects received entecavir 0.5 mg/day (Bristol-Myers Squibb, Shanghai) monotherapy. Routine hematologic analysis, hepatobiliary enzymes, HBV DNA, and serologic analysis, hepatic synthetic function, creatine kinase, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, blood lactate were assayed at base line and every 3-6 months thereafter. A 2 mL blood sample was collected at each follow-up for future assessment. Genotypic resistance was also assessed (1) in all HBV patients who had PVR; or (2) at baseline in 25 ETV-naïve HBV voluntary patients. The diagnosis of cirrhosis was based on histology or ultrasound examinations. The patients were carefully examined at each follow-up visit and asked to report any incidence of adverse events.

Endpoints

Primary endpoint was the proportions of patients achieving virological response (undetectable HBV DNA<100 IU/mL) at month 3, month 6, 1 year, 2 years, 3 years, 4 years and 5 years. Secondary endpoints were HBeAg loss and seroconversion, ALT normalization, and genotypic resistance testing. Partial virological response was defined as a decrease in HBV DNA of more than 2.0 log10 IU/mL but detectable HBV DNA by real-time PCR assay (100 IU/mL) at 48 weeks of ETV treatment [11].

Assay methods

Liver function and other biochemical indexes assays were measured using automated techniques. Serum HBV DNA levels were measured using a quantitative real-time PCR assay (DAAN Gene Co., Ltd., Guangzhou, China), with a lower limit of detection of 100 IU/mL. HBsAg, anti-HBs, HBeAg, and anti-HBe were measured using commercially available chemiluminescence assay kits (Roche Diagnostic Systems). Detection of HBV polymerase gene mutations was determined by direct sequencing PCR method (BGI-Shenzhen, Shenzhen, China).

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using the SPSS software package version 13.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Quantitative data were presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Categorical data were presented as counts and percentages. HBV DNA levels were presented as log transformation. Student's t test was used for quantitative data. Pearson chi-square and Fisher exact tests were used for categorical variables. Logistic regression analysis was used to investigate the factors were associated with PVR to ETV monotherapy. A two-tailed p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Subject disposition

Baseline characteristics of the study population are presented in Table 1. In total, 230 patients were treated with ETV 0.5 mg/day, of whom 113 were HBeAg-positive and 117 were HBeAg-negative. Overall, 85.2% (n=196) were male, 141 (61.3%) had family history of HBV infection, 74 (32.2%) patients had cirrhosis. Mean HBV DNA was 6.3 log10IU/mL. Mean age was 42 years and Median follow-up of the whole study population was 28(3-73) months. Among 230 NA-naïve CHB patients in our current study, 28 experienced interferon therapy. 25 patients were male, the mean age was 39 years, and the mean body mass index was 25.8. Mean HBV DNA was 6.7 log10IU/mL, 13 patients was HBeAg positive. 6 cases were treated pegylated interferon, 22 cases were treated conventional interferon. Fourteen patients were on treatment less than 1 month because of the high cost and poor compliance. Nine had been treated for 1 year and then were terminated therapy after achieving vriologic response. All these 9 patients finally developed virologic rebound at 2 years after cessation of interferon therapy. Another 5 patients failed to achieve response after 6 months-treatment and switched to ETV.

Characteristics of patients at baseline

| Baseline demographics | Total (n=230) | HBeAg -positive (n=113) | HBeAg -negative (n=117) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (%) | 196(85.2) | 91(80.5) | 105(89.7) | 0.144 |

| Age (years, mean) | 42±12 | 37±10 | 46±12 | 0.001 |

| Body mass index | 22.7±3.1 | 22.7±3.11 | 22.8±3.1 | 0.938 |

| Follow-up ,months( median) | 28(3-73) | 23(3-65) | 30(3-73) | 0.167 |

| Family history of HBV (%) | 141(61.3) | 75(66.4) | 66(56.4) | 0.301 |

| Presence of cirrhosis (%) | 74(32.2) | 26(23.0) | 48(41.0) | 0.014 |

| Presence of hepatocellular carcinoma | 14(6.1) | 6(5.3) | 8(6.8) | 0.889 |

| Interferon experienced | 28(12.2) | 13(11.5) | 15(12.8) | 0.955 |

| ALT (U/L, median) | 68(3-2631) | 78(15-1539) | 63(3-2631) | 0.926 |

| HBV DNA (log10IU/mL) | 6.3±1.4 | 6.7±1.3 | 5.9±1.3 | 0.580 |

Efficacy of ETV in NA-naïve patients

Of 230 patients received ETV treatment for at least 3 months, The cumulative probability of achieving virological response at 3 months, 6 months, 1 year, 2 years, 3 years, 4 years, and 5 years was 67.0%, 85.0%, 89.4%, 94.4%, 95.5%, 97.6%, 100%, respectively (Fig. 1). Proportion of patients with normal ALT was 73.9%, 85.5%, 82.8%, 89.4%, 80.7%, 85.7% and 100% (Fig. 2). Among the 113 HBeAg-positive patients at baseline, 80.5% (n=91) were male, with a median follow-up of 23 (3-65) months. Mean HBV DNA was 6.7log10IU/mL (Table 1). The cumulative probability of achieving virological response at 3 months, 6 months, 1 year, 2 years, 3 years, 4 years, and 5 years was 60.2%, 76.7%, 85.2%, 89.9%, 92.9%, 92.3% and 100%, respectively. Proportion of patients with normal ALT was 68.1%, 85.4%, 78.4%, 88.4%, 71.4%, 84.6% and 100%. Rate of HBeAg seroconversion at 1, 2, 3, and 4 years was 15.9%, 21.7%, 21.4%, 15.4%, respectively (Fig. 3). One patient achieved HBsAg seroclearance after 1 year, and achieved anti-HBs seroconversion at year 3. In 117 HBeAg-negative patients at baseline, those who achieved virological response at 3 months, 6 months, 1 year, 2 years, 3 years, 4 years, and 5 years was 73.5%, 92.8%, 93.5%, 98.6%, 97.8% and 100%, respectively. The respective percentages of patients with normal ALT levels were 79.5%, 85.6%, 87.0%, 90.4%, 89.1%, 86.2%, and 100%.

Percentages of patients who had undetectable serum HBV DNA from month 3 to year 5.

Percentages of patients who had ALT normalization from month 3 to year 5.

Percentages of patients who had HBeAg seroconversion from month 3 to year 5.

Partial virological response in NA-naïve patients

Baseline demographics and disease characteristics of patients who gained PVR after 1 year were summarized in Table 2. Nineteen (19/180, 10.6%) patients achieved PVR after 1 year of treatment. The univariate and multivariate Logistic regression model were applied for high risk factors analysis for having a PVR. High baseline HBVDNA levels (OR,0.532; 95%CI,0.315-0.896; P=0.018) and virological non-response at week 24 (OR,6.093; 95%CI,2.099-17.685; P=0.001) to ETV monotherapy were the independent risk factors for a PVR at 1 year (Table 3). Twelve of 14 (85.7%) patients with PVR need more than 1 year of continuous ETV therapy to achieved VR (Table 2). Among the remained 5 patients, 3 patients were switched to ETV+ ADV combination therapy (One of these three patients developed ETV resistance due to noncompliance). 12 patients were followed up to 3 years, and 100% (12/12) achieved virological response. Four patients achieved virological response during follow up to year 4.

Resistance

Twenty-five ETV-naïve patients had genotypic resistance testing at baseline. One showed ADV resistance (rtN236T). No mutation associated with resistance to LAM or ETV was revealed.

19 of ETV-naïve patients with PVR at 1 year had genotypic resistance detection. Among them, Only one patient developed ETV resistance (rtL180M + rtT184A + rtM204V) after ETV treatment for 1 year. Subsequently, it was switched to ETV+ADV combination therapy.

Safety

No severe adverse event was reported during the study. During follow-up, Transient elevations of creatine kinase were detected among 31 patients. They all had no muscle aches. In questioning history, these patients had a certain amount of exercise (such as playing basketball, climbing, and running). After reducing the amount of exercise, creatine kinase was restored to normal. None of the patients developed clinically evident elevated blood lactate (normal range 0.5-1.7mmol/L). To assess renal safety, we analyzed creatinine levels in a subset of 147 patients with an available baseline creatinine level. Sustained slightly elevated creatinine was observed in one patient who had been gone through hepatectomy. Eighteen patients developed hepatocellular carcinoma, of whom 15 was already present at the start of ETV treatment and 3 (who had a history of cirrhosis) were diagnosed during ETV treatment.

Baseline demographics and disease characteristics of patients who gained partial virological response after 1 year treatment.

| 1 year n=19 | 2 years n=14 | 3 years n=12 | 4 years n=4 | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (%) | 17 (89.5) | 12 (85.7) | 11 (91.7) | 4 (100) | 0.860 |

| Age(years, mean) | 40±11 | 41±12 | 43±12 | 42±16 | 0.937 |

| Body mass index | 22.0±2.4 | 21.3±2.4 | 21.6±2.4 | 22.9±0.9 | 0.651 |

| HBV DNA at baseline (log10 IU/mL) | 7.1±0.8 | 6.9±0.9 | 6.9±0.9 | 7.1±1.0 | 0.950 |

| HBeAg positive at baseline(n) | 13 (68.4) | 8 (57.1) | 7 (58.3) | 2 (50.0) | 0.857 |

| Virologic response (%) | 12(85.7) | 12(100) | 4(100) | 0.294 |

Univariate and multivariate analyses of host and viral factors associated with undetectable levels of HBV DNA at year 1.

| Parameter | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O R | ( 95% CI ) | P | O R | ( 95% CI ) | P | |

| Sex | 0.640 | 0.139-2.944 | 0.567 | |||

| Age (years) | 1.019 | 0.977-1.064 | 0.381 | |||

| Body mass index | 1.136 | 0.967-1.334 | 0.121 | |||

| HBeAg state at baseline | 0.393 | 0.142-1.084 | 0.071 | |||

| HBV DNA level at baseline (log10IU/ml) | 0.458 | 0.281-0.748 | 0.002 | 0.532 | 0.315-0.896 | 0.018 |

| ALT level at baseline (U/L) | 0.999 | 0.997-1.100 | 1.132 | |||

| HBV family history | 0.757 | 0.273-2.095 | 0.591 | |||

| Presence of cirrhosis | 1.535 | 0.526-4.478 | 0.433 | |||

| Virological response at week 12 | 2.550 | 0.970-6.705 | 0.058 | |||

| Virological response at week 24 | 8.827 | 3.166-24.610 | 0.000 | 6.093 | 2.099-17.685 | 0.001 |

Discussion

Compared with other available nucleos(t)ide analogs, ETV achieves more potent HBV DNA suppression than all agents except perhaps TDF, which is equivalent [12]. Our previous study [13] has shown that ETV had better rate of virologic response, lower incidence of resistance, commensurable safety as well as seroconversion rate when compared to LAM, ADV, LdT. In the registration trials of ETV, rates of genotypic resistance were rare in both HBeAg-positive and HBeAg-negative patients. Because of potent viral suppression and a large genetic barrier to resistance, ETV is recommended as a first-line choice in HBV treatment guidelines.

This present results show that a gradual increase of the cumulative virological response rate in ETV-naïve patients at all time points through treatment for up to 5 years in real life. More than 90% patients had HBV DNA undetectable after 2 years. There was obvious serum HBV DNA reduction and increased virological response at 12 weeks and 24 weeks, which confirms ETV to be a highly potent antiviral agent. The rate of ALT normalization was increased over time too. Rate of HBeAg seroconversion at 2 years and 3 years were 21.7% and 21.4%, which are consistent with previous results [14-17]. All included patients in this study were NA-naïve, 28(12.2%) of which had experience of interferon. Since the antiviral and immunoregulatory effects of interferon, it has been approved for first-line treatment option of CHB. However, it is still unsure how previous interferon exposure affects the efficacy of ETV therapy. But in this study, the proportion of interferon -experienced cases was not high. Their duration of treatment was mostly less than 1 month, or at least 2 years away from the start of ETV therapy. Thus, the impact of interferon to ETV therapy may be limited.

In this study, a small number of ETV-naïve patients (19/180) achieved PVR after 1 year of ETV treatment, similar with that of previous results (10%-30%) [9]. The present study investigated several baseline and viral factors that may influence the antiviral efficacy [18-19]. We further analyzed the high risk factors of patients with PVR by applying the univariate and multivariate Logistic regression model. It is stated that VR of ETV-naïve patients at year 1 was significantly affected by baseline HBV DNA level, VR at month 6, while gender, age, BMI, hepatitis B family history, baseline ALT level, VR at month 3 were irrelevant to VR at week 48. In other words, it was easier to achieve VR at year 1 in patients with lower baseline HBV DNA level and in those who achieved VR at month 6. Therefore, it was recommended that ETV-naïve patients with PVR should be managed differently according to treatment response and baseline HBV DNA level, if they are compliant [20]. Marcellin et al [21] suggested that the characteristics of the patients and virus were important when assessing the chance of success and when choosing the best therapeutic strategy. In a word, more and more data needed to allow a more personalized approach for optimizing treatment in individual patients.

The clinical relevance of NAs PVR relates to the high risk these patients face of developing resistance to long-term anti-HBV treatment, particularly when LAM and LdT are involved [22]. Treatment adaptation is suggested in the roadmap for management of patients with PVR receiving oral therapy for chronic hepatitis B proposed by Keeffe et al [23-24]. But ETV is a large genetic barrier to resistance drug, Long-term monitoring showed low rates of resistance in nucleoside-naïve patients during 5 years of ETV therapy. Thus, this strategy for patients with PVR may be different from LAM and LdT. It was reported that ETV monotherapy can be continued in NA-naïve patients with detectable HBV DNA at week 48, particularly in those with a low viral load, because long-term ETV leads to a virological response in the vast majority of patients [18]. We continued ETV therapy in 19 patients with detectable HBV DNA at year 1. Virological response was achieved in 85.7% (12/14), 100%(12/12), 100%(4/4) of NA-naïve patients at 2 years, 3 years, and 4 years, respectively. Most of the patients can finally achieve virological response if therapy is continued beyond 1 year. On the other hand, a sustained low viremia were found in patients with PVR to 48-week ETV monotherapy. In addition, ETV resistance is unique because it requires up to three mutations for full resistance to develop [25]. In this study, only one patient with PVR developed ETV resistance (rtL180M + rtT184A + rtM204V) after ETV treatment for 1 year. The reason is this patient did not take medicine following the doctor,s medical advice. Thus, it was suggested that adjustment of ETV monotherapy in NA-naïve patients with a PVR at 1 year may be unnecessary in real life. Whether this kind of therapy would increase risk of resistance in longer time or not is undefined, which need further study.

HBV has quasispecies characteristics and can have various mutations before NAs treatment, possibly responsible for pre-existing resistance [26-27]. Though the occurrence of pre-existing resistance is rare, it has been found to eliminate the antiviral efficacy of LAM therapy [28]. But for ADV, its primary non-response was considered irrelevant to pre-existing resistance [29]. In this study, we had not detected pre-existing resistance in all ETV-naïve patients because of the high cost. Genotypic resistance at baseline was tested in 25 ETV-naïve voluntary patients and no mutation associated with resistance to ETV was revealed. ETV has rare occurrence of resistance in NA-naive patients [30]. Considering cost-effectiveness, detecting mutations for pre-existing resistance to ETV in NA-naive patients is of limited significance. In contrast, a reduced barrier to resistance was observed in LAM-refractory patients, resulting in a 5-year cumulative probability of genotypic ETV-resistance of 51% [30]. It's reported that prior ADV-experience or even presence of ADV-resistance did not influence antiviral response to ETV. Presence of LAM-resistant mutations at the start of ETV monotherapy was significantly associated with a reduced probability of achieving virological response [31]. Therefore, Genotypic resistance testing before initiating ETV treatment is not necessary for NA-naive patients, but necessary for LAM-experienced patients regardless with LAM-resistance or not.

In conclusion, long-term treatment of ETV 0.5 mg/day for up to 5 years suppressed HBV-DNA to undetectable levels in more than 90% of ETV-naïve chronic hepatitis B patients. Adjustment of ETV monotherapy in NA-naive patients with a PVR at 1 year may be not needed, if ETV resistance did not happen. Most patients could achieve virological response if therapy was continued beyond 1 year. Moreover, it was also a very safe antiviral agent.

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by the 11th five-year National Science and Technology Major Project (NO. 2009ZX10001-018), and funded by Sino-American Shanghai Squibb Pharmaceuticals Ltd.

Competing Interests

The authors have declared that no competing interest exists.

References

1. Liaw YF, Kao JH, Piratvisuth T. et al. Asian-Pacific consensus statement on the management of chronic hepatitis B: a 2012 update. Hepatol Int. 2012;6:531-561

2. Chang TT, Gish RG, de Man R. et al. A comparison of entecavir and lamivudine for HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B. New Engl J Med. 2006;354:1001-1010

3. Lai CL, Shouval D, Lok AS. et al. Entecavir versus lamivudine for patients with HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B. New Engl J Med. 2006;354:1011-1020

4. Chang TT, Chao YC, Gorbakov VV. et al. Results of up to 2 years of entecavir vs lamivudine therapy in nucleoside-naïve HBeAg-positive patients with chronic hepatitis B. J Viral Hepat. 2009;16:784-789

5. Chang TT, Lai CL, Yoon SK. et al. Entecavir treatment for up to 5 years in patients with hepatitis B e antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2010;51:422-430

6. Yokosuka O, Takaguchi K, Fujioka S. et al. Long-term use of entecavir in nucleoside -naive Japanese patients with chronic hepatitis B infection. J Hepatol. 2010;52:791-799

7. Lai CL, Gane E, Liaw YF. et al. Telbivudine versus lamivudine in patients with chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2576-2588

8. Liaw YF, Gane E, Leung N. et al. 2-Year GLOBE trial results: telbivudine is superior to lamivudine in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:486-495

9. Lampertico P. Partial virological response to nucleos(t)ide analogues in naïve patients with chronic hepatitis B: From guidelines to field practice. J Hepatol. 2009;50:644-647

10. Chinese Society of Hepatology, Chinese Society of Infectious Diseases, Chinese Medical Association. The Guideline of Prevention and Treatment for Chronic Hepatitis B (2010 Version). Chin J Exp Clin Infect Dis (Electronic Version). 2011;5:79-100

11. Li LJ, Hou JL. Experts proposal on combination therapy of nucleos(t)ide analogues for chronic hepatitis B. Chin J Clin Infect Dis. 2011;4:65-68

12. Osborn M. Safety and efficacy of entecavir for the treatment of chronic hepatitis B. Infection and Drug Resistance. 2011;4:55-64

13. Wu YK, Li XY, Lin GL. et al. Comparation of the efficacy of lamivudine, adefovir dipivoxil, telbivudine and entecavir in treating NAs-naive patients with chronic HBV infection: 4-year real life data. Hepatology. 2012;56(Suppl):377A

14. Yao GB, Ren H, Xu DZ. et al. Results of 3 years of continuous entecavir treatment in nucleos(t)ide-naive chronic hepatitis B patients. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi. 2009;17:881-886

15. Ono A, Suzuki F, Kawamura Y. et al. Long-term continuous entecavir therapy in nucleos(t)ide -naïve chronic hepatitis B patients. J Hepatol. 2012;57:508-514

16. Lam YF, Yuen MF, Seto WK. et al. Current antiviral therapy of chronic hepatitis B: efficacy and Safety. Curr Hepatitis Rep. 2011;10:235-243

17. Yuen MF, Seto WK, Fung J. et al. Three years of continuous entecavir therapy in treatment -naïve chronic hepatitis B patients: Viral suppression, viral resistance, and clinical safety. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1264-1271

18. Zoutendijk R, Reijnders JG, Brown A. et al. Entecavir treatment for chronic hepatitis B: Adaptation is not needed for the majority of naïve patients with a partial virological response. Hepatology. 2011;54:443-451

19. European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2012;57:167-185

20. Chon YE, Kim SU, Lee CK. et al. Partial virological response to entecavir in treatment-naïve patients with chronic hepatitis B. Antiviral Therapy. 2011;16:469-477

21. Marcellin P, Liang J. A personalized approach to optimize hepatitis B treatment in treatment -naïve patients. Antiviral therapy. 2010;15(suppl 3):53-59

22. European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL clinical practice guidelines: management of chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2009;50:227-242

23. Keeffe EB, Zeuzem S, Koff RS. et al. Report of an international workshop: Roadmap for management of patients receiving oral therapy for chronic hepatitis B. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:890-897

24. Keeffe EB, Dieterich DT, Han SH. et al. A treatment algorithm for the management of chronic hepatitis B virus Infection in the United States: 2008 Update. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:1315-1341

25. Tenney DJ, Levine SM, Rose RE. et al. Clinical emergence of entecavir-resistant hepatitis B virus requires additional substitutions in virus already resistant to lamivudine. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:3498-3507

26. Mirandola S, Campagnolo D, Bortoletto G. et al. Large-scale survey of naturally occurring HBV polymerase mutations associated with anti-HBV drug resistance in untreated patients with chronic hepatitis B. Journal of Viral Hepatitis. 2011;18:e212-e216

27. Fung SK, Mazzulli T, Sherman M. et al. Pre-existing antiviral resistance mutations among treatment naïve HBV patients can be detected by a sensitive line probe assay. J Hepatol. 2008;48(Suppl 2):S256

28. Fung S, Wong F, Mazzulli T. et al. Pre-existing antiviral-resistant mutation may be associated with primary non-response to lamivudine among treatment-naïve chronic hepatitis B patients. Hepatology. 2009;50(Suppl):523A

29. Carrouee-Durantel S, Durantel D, Werle-Lapostolle B. et al. Suboptimal response to adefovir dipivoxil therapy for chronic hepatitis B in nucleoside-naïve patients is not due to pre-existing drug-resistant mutants. Antivir Ther. 2008;13:381-388

30. Tenney DJ, Rose RE, Baldick CJ. et al. Long-term monitoring shows hepatitis B virus resistance to entecavir in nucleoside-naïve patients is rare through 5 years of therapy. Hepatology. 2009;49:1503-1514

31. Reijnders JG, Deterding K, Petersen J. et al. Antiviral effect of entecavir in chronic hepatitis B: Influence of prior exposure to nucleos(t)ide analogues. J Hepatol. 2010;52:493-500

Author contact

![]() Corresponding author: Yutian Chong, MD, PhD. Address: Department of Infectious Diseases, The Third Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University, Tianhe Road No. 600, Guangzhou 510630, China. Tel & Fax: +86-010-85252378. E-mail: ytchong2005com.

Corresponding author: Yutian Chong, MD, PhD. Address: Department of Infectious Diseases, The Third Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University, Tianhe Road No. 600, Guangzhou 510630, China. Tel & Fax: +86-010-85252378. E-mail: ytchong2005com.

Global reach, higher impact

Global reach, higher impact