Impact Factor

ISSN: 1449-1907

Int J Med Sci 2012; 9(1):65-67. doi:10.7150/ijms.9.65 This issue Cite

Case Report

Delayed Intracerebral Hemorrhage Secondary to Ventriculoperitoneal Shunt: Two Case Reports and a Literature Review

Department of Neurosurgery, Second Affiliated Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University, China.

Received 2011-9-21; Accepted 2011-11-20; Published 2011-11-24

Abstract

Ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunt has become a popular operation to achieve cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) diversion, but is associated with many complications. Postoperative delayed intracerebral hemorrhage is a kind of rare but severe event, which has not thus far been reported in retrospective case analyses. Here we present two cases of delayed intracerebral hemorrhage, along the path of the ventricular catheter, which occurred on postoperative days 3 and 5. We also provide a literature review regarding this rare complication.

Keywords: delayed, intracerebral hemorrhage, ventriculoperitoneal shunt.

Introduction

The ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunt is routinely used for cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) diversion. A relatively straightforward procedure, it can be done safely even in infancy. However, placement of the VP shunt may be associated with several complications (infection, shunt malfunction, subdural hematoma, seizures, migrating catheter)1. Small amounts of blood are frequently seen on imaging in the ventricle or in the parenchyma along the catheter path, but clinically significant hemorrhage is rare2,3. In fact, postoperative intracerebral or intraventricular hemorrhage secondary to shunt placement is rare; only a few such patients have been reported4,5,6. In 1985, Matsumura reported the first case of delayed intracerebral hemorrhage after VP shunting in a 17-year-old male on postoperative day 75. The clinical features and mechanisms underlying this event are not clearly understood.

We report two cases of delayed intracerebral hemorrhage, along the path of the ventricular catheter, occurring on postoperative days 3 and 5. We also present a literature review regarding this rare complication.

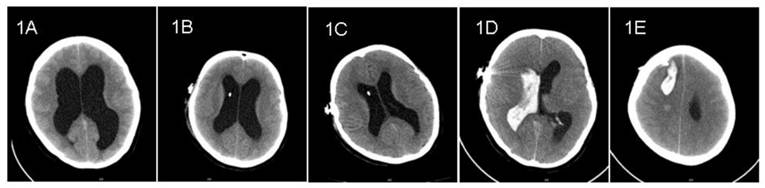

Case 1: A 32-year-old female complained of headache and dizziness for 2-month duration. Computed tomography (CT) showed markedly enlarged ventricles (Figure 1A). There were no space-occupying lesions on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Lumbar puncture revealed transparent CSF with an initial opening pressure of 255 mm H2O. A diagnosis of hydrocephalus was made and a VP shunt undertaken with a Medtronic Strata Programmable Valve System (pressure level, 2.5). Preoperative laboratory evaluation showed a normal prothrombin time (PT). The patient was not receiving anti-platelet or anti-coagulation medication. The VP shunt was inserted at the first attempt; no blood was observed in the CSF on ventricular cannulation. The patient recovered well and routine follow-up CT on postoperative days 1 and 3 showed collapsing ventricles without evidence of hemorrhage (Figure 1B, 1C). On postoperative day 5, the patient suddenly developed a headache and dizziness while urinating. Soon thereafter, the patient became unconscious; CT showed a large hematoma along the path of the ventricular catheter associated with an appreciable intraventricular hemorrhage (Figure 1D, 1E). Unfortunately, the patient died suddenly before evacuation of the hematoma was possible.

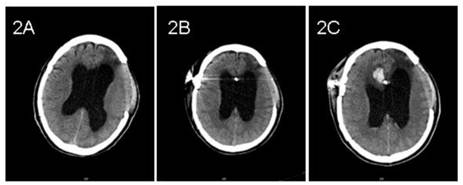

Case 2: A 58-year-old male underwent a decompressive left frontotemporal craniectomy and right frontotemporal craniotomy for traumatic intracerebral hematoma sustained during a motor vehicle collision 3 months previously. CT showed hydrocephalus with interstitial edema capping the frontal horns of the lateral ventricles (Figure 2A). Preoperative neurological examination was unremarkable. A VP shunt was placed with a Medtronic Strata Programmable Valve System (pressure level, 1.5). A ventricular catheter was inserted into the anterior horn of the right lateral ventricle at the first attempt. Twenty-four hours after surgery, CT imaging was normal and the pressure of the left decompressive window decreased (Figure 2B). On postoperative day 3, the pressure increased and the patient deteriorated. Emergent CT demonstrated hemorrhage along the path of the ventricular catheter and in both lateral ventricles (Figure 2C). The patient was treated conservatively and recovered gradually with a patent shunt tube.

Discussion

Delayed intracerebral or intraventricular hemorrhage after placement of a VP shunt has been reported, but is very rare2,7,8. In our institution, the prevalence is 1.08% (2/186) in the past 5 years.

Literature reviews revealed that almost all instances of postoperative intracerebral hemorrhage secondary to VP shunt placement occurred soon after the operation9. The hemorrhage might be caused by multiple attempts at ventricular puncture, puncture of the choroid plexus or incorrect placement of the tube within the brain parenchyma6,10,11. Other mechanisms whereby intracerebral hemorrhage might occur after ventricular cannulation included a coexistent bleeding disorder, disruption of an intracerebral vessel, hemorrhage from an occult vascular malformation and head trauma occurring shortly after shunt placement4.

Pre- and post- operative CT imaging of case 1. 1A: Preoperative CT showed enlarged ventricles. 1B and 1C: CT showed shrinking ventricles on postoperative days 1 and 3. 1D and 1E: CT on postoperative day 5 showed intraventricular hemorrhage and intracerebral hematoma along the path of ventricular catheter.

Pre- and post- operative CT imaging of case 2. 2A: Preoperative CT showed hydrocephalus. 2B: Routine CT showed no evidence of hemorrhage on postoperative day 1. 2C: CT showed hemorrhage along the path of ventricular catheter on postoperative day 3.

Literature review of cases of delayed intracerebral hemorrhage after ventriculoperitoneal shunt insertion.

| Series | Age(sex) | Primary disease | Shunt operation | Onset day of hemorrhage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site | Operative finding | ||||

| Matusmura et al (1985) | 17 (M) | brain contusion | AH | Uneventful | 7 |

| Snow et al (1986) | 43 (F) | iNPH | AH | Uneventful | 5-7 |

| Alcarza et al (2007) | 64 (F) | SAH | AH | Uneventful | 6 |

| Misaki et al (2010) | 55 (M) | SAH, meningitis | PH | Uneventful | 7 |

| Misaki et al (2010) | 64 (M) | SAH, meningitis | PH | Uneventful | 6-13 |

| Case 1 | 32 (F) | no | AH | Uneventful | 5 |

| Case 2 | 58 (M) | brain contusion | AH | Uneventful | 3 |

AH: anterior horn of lateral ventricle, iNPH: idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus, PH: posterior horn of lateral ventricle, SAH: subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Neither of our two patients had any of the above predisposing risk factors. Misaki and Alcazar explored the mechanism underlying the delayed aspect of the hemorrhage, suggesting erosion of cerebral blood vessels from the catheter as an explanation12,13. Although this did not explain all post-shunt hemorrhages, we thought that ventricular collapse after tube insertion (postoperative CT imaging can show this) might induce the tighter contact between the catheter and vasculature and lead to subsequent erosion of the vasculature. This may (at least in part) explain the delayed aspect of the hemorrhage. We summarized the reported cases of delayed intracerebral hemorrhage after shunt insertion based on the work of Misaki13 (Table 1).

In conclusion, delayed intracerebral hemorrhage secondary to VP shunt is a rare but severe complication with a high mortality rate. We suggest that CT should be undertaken on postoperative day 1 after shunt insertion. Repeat CT or MRI is necessary if the patient complains of additional symptoms.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

References

1. Wu Y, Green NL, Wrensch MR, Zhao S, Gupta N. ventriculoperitoneal shunt complications in California: 1990-2000. Neurosurg. 2007;61:557-62

2. Ivan LP, Choo SH, Ventureyra ECG. Complications of ventriculoatrial and ventriculoperitoneal shunts in a New Children's Hospital. Can J Surg. 1980;23:566-8

3. Palmieri A, Pasquini U, Menichelli F, Salvolini U. Cerebral damage following ventricular shunt for infantile hydrocephulus evaluated by computed tomography. Neuroradiol. 1981;21:33-5

4. Snow RB, Zimmerman RD, Devinsky O. Delayed intracerebral hemorrhage after ventriculoperitoneal shunting. Neurosurg. 1986;19:305-7

5. Matsumura A, Shinohara A, Munekata K, Maki Y. Delayed intracerebral hemorrhage after ventriculoperitoneal shunt. Surg Neurol. 1985;24:503-6

6. Savitz MH, Bobroff LM. Low incidence of delayed intracerebral hemorrhage secondary to ventriculoperitoneal shunt insertion. J Neurosurg. 1999;91:32-4

7. Kuwamura K, Kokunai T. Intraventricular hematoma secondary to a ventriculoperitoneal shunt. Neurosurg. 1982;10:384-6

8. Udvarhelyi GB, Wood JH, James AE, Bartlet D. Results and complications in 55 shunted patients with normal pressure hydrocephalus. Surg Neurol. 1975;3:271-5

9. Fukamachi A, Koizumi H, Nukui H. Postoperative intracerebral hemorrhages: a survey of computed tomographic findings after 1074 intracrainal operations. Surg Neurol. 1985;23:575-80

10. Derdeyn CP, Delashaw JB, Broaddus WC, Jane JA. Detection of shunt-induced intracerebral hemorrhage by postoperative skull films: a report of two cases. Neurosurg. 1988;22:755-7

11. Lund-Johansen M, Svendsen F, Wester K. Shunt failures and complications in adults as related to shunt type, diagnosis and the experience of the surgeon. Neurosurg. 1994;35:839-44

12. Alcazar L, Alfaro R, Tamarit M. et al. Delayed intracerebral hemorrhage after ventriculoperitoneal shunt insertion. Case report and literature review. Neurocirugia (Astur). 2007;18:128-33

13. Misaki K, Uchiyama N, Hayashi Y, Hamada J. Intracerebral hemorrhage secondary to ventriculoperitoneal shunt insertion-four cases report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2010;50:76-9

Author contact

![]() Corresponding author: Dr Xiangdong Zhu, MD. Department of Neurosurgery, Second Affiliated Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University. Address: Jiefang Road 88, Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province, China. Zip code: 310009 Tel: +86 571 87784716 Email: zhuxdcom

Corresponding author: Dr Xiangdong Zhu, MD. Department of Neurosurgery, Second Affiliated Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University. Address: Jiefang Road 88, Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province, China. Zip code: 310009 Tel: +86 571 87784716 Email: zhuxdcom

Global reach, higher impact

Global reach, higher impact