Impact Factor

ISSN: 1449-1907

Int J Med Sci 2012; 9(1):59-64. doi:10.7150/ijms.9.59 This issue Cite

Research Paper

A Randomized Clinical Trial Comparing the Effect of Rapidly Infused Crystalloids on Acid-Base Status in Dehydrated Patients in the Emergency Department

1. Department of Emergency Medicine, Gulhane Military Medical Academy, GATA Acil Tip Anabilim Dali, Etlik, Ankara, Turkey 06010.

2. School of Medicine, University of Utah, 30 N. 1900 E. 1C26, Salt Lake City, UT 84132, USA.

Received 2011-9-26; Accepted 2011-11-16; Published 2011-11-23

Abstract

Study objective: To compare the effect of normal saline (NS), lactated Ringer's, and Plasmalyte on the acid-base status of dehydrated patients in the emergency department (ED).

Method: We conducted a prospective, double-blind, randomized trial of consecutive adult patients who presented to the emergency department with moderate-severe dehydration. Patients were randomly allocated to blindly receive normal saline (NS), lactated Ringer's or Plasmalyte at 20 ml/kg/h for 2 hours. Outcome measures of the study were pH and changes in electrolytes, including serum potassium, sodium, chloride and bicarbonate levels at 0, 60, and 120 minutes in venous blood gas samples.

Results: Ninety patients participated in the study and were randomized to NS (30 patients), lactated Ringer's (30 patients) and Plasmalyte (30 patients) groups. Mean age was 48±20 years and 50% (n=45) of the patients were female. All pH values were in the physiological range (7.35-7.45) throughout the study period. In the NS group there was a significant tendency to lower pH values, with pH values of 7.40, 7.37, and 7.36 at 0, 1, and 2 hours respectively. Average bicarbonate levels fell in the NS group (23.1, 22.2, and 21.5 mM/L) and increased in the Plasmalyte group (23.4, 23.9, and 24.4 mM/L) at 0, 1, and 2 hours, respectively. There were no significant changes in potassium, sodium, or chloride levels.

Conclusions: NS, lactated Ringer's, and Plasmalyte have no significant effect on acid-base status and all can be used safely to treat dehydrated patients in the emergency department. However, NS can effect acidosis which might be significant in patients who have underlying metabolic disturbances; thus, its use should be weighed before fluid administration in the ED.

Keywords: normal saline, crystalloids, acid-base status, dehydrated patients

Introduction

The maintenance of intravascular volume is essential in many clinical scenarios, such as severe dehydration and hypovolemic shock, in the emergency department (ED). Crystalloids, including normal saline (NS), lactated Ringer's, and Plasmalyte, are the preferred first-line treatments for such patients [1]. In particular, NS, which is known as physiological serum, is used widely as a well-known, traditional option in situations that require liquid therapy.

NS is significantly hypertonic (osmolality 308 mOsm/L) and contains very high chloride content. NS can cause metabolic acidosis, calling into question its 'normal' and 'physiological' properties [2-4]. High chloride content, the dilution effect due to extravascular bicarbonate, and a strong ion difference (SID) per Stewart's formula have been implicated as causes of acidosis [5].

The frequency and clinical significance of NS-induced acidosis, however, is not well described. Furthermore, in patients presenting to the ED with underlying metabolic disturbances, such as renal failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, choosing the right crystalloid that is associated with the best metabolic profile for the patient becomes more critical [6]. Although crystalloids are used routinely to treat hypovolemia in ED settings, limited data exist on their effects on acid-base status.

In this study, we compared the effect of NS, lactated Ringer's, and Plasmalyte on the acid-base status of dehydrated patients in the emergency department.

METHODS

Study design and setting

We conducted a randomized, double-blind, controlled trial of adults who received intravenous rehydration treatment from April 2009 until July 2010, in an ED that had an annual census of 120,000 patient visits. The institutional review board approved the study, and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Selection of participants

Attending physicians in the ED enrolled patients with signs of moderate and severe dehydration. Moderate and severe dehydration was defined as dry mucous membranes, systolic blood pressure lower than 90 mm Hg, heart rate higher than 100/min and intolerance of oral intake of liquids. Exclusion criteria were age <18 years, severe cardiovascular disease, liver dysfunction, serum potassium levels higher than 5.5 mM/L, acute pulmonary edema, and shock.

Interventions

Patients were randomized to 3 groups: Normal saline, lactated Ringer's and Plasmalyte. The randomization scheme was generated using a web-based program for randomization (http://www.randomization.com). The study solutions were unlabeled or covered. Solutions were numbered per the randomization scheme. Patients and treating physicians were blinded to the treatment. After the treating physician determined a patient's eligibility for the study, a study nurse was ordered to prepare the crystalloid solution per the randomization scheme. Another nurse, blinded to the study, administered the crystalloid solutions at 20 ml/kg/h for 2 hr. Two 16-gauge IV line were placed at each arm of the patient- one for infusion of the crystalloid fluid and the other for drawing blood samples.

Methods of measurement

Patient data, including demographics, medical history, and physical examination, were recorded by the treating physician. Venous blood gas samples were collected at 0, 60, and 120 minutes.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome of the study was change in pH in venous blood gas samples at 60 and 120 minutes. Secondary outcome measures were the changes in electrolytes, including serum potassium, sodium, chloride, and bicarbonate levels at 60 and 120 minutes.

Primary data analysis

We calculated that a minimum of 17 patients in each group would be required to detect a 0.05-unit difference between groups, assuming a standard deviation of 0.05 with 80% power at a 2-sided alpha level of 0.05.

Descriptive statistics were expressed as frequency (percentage) for categorical variables whereas continuous data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation for normally distributed data and median interquartile range (IQR) for non-normally distributed data. Metabolic parameters between groups were compared by analysis of variance. Homogeneity of variances was tested by Levene's test, and Tukey test was used for post hoc analysis between groups. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 16 (Chicago, IL) and p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

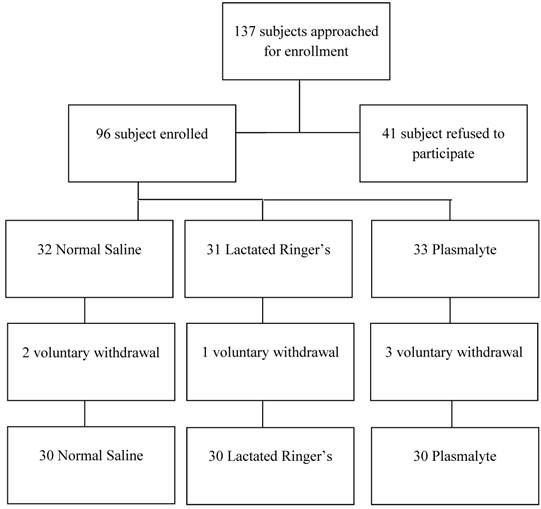

We screened 137 patients for eligibility, 41 of whom were excluded for meeting at least one of the predefined exclusion criteria or declining to participate (Figure 1). Ninety-five patients were randomized to the three treatment arms and 5 withdrew their consent during the study. Ultimately, 90 patients were included in the final analysis (n=30 in each group); 50% (n=45) of the patients were females, with a mean age of 48±20 years. Patient demographics were presented in Table 2.

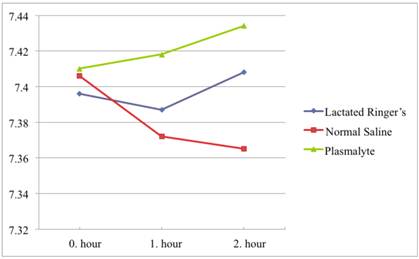

All pH values were in the physiological range (7.35-7.45). In the NS group there was a significant tendency to lower pH values with pH values of 7.40, 7.37, and 7.36 at 0, 1, and 2 hours, respectively. In contrast, pH did not change significantly in the Plasmalyte or Lactated Ringer's group. The average pH in the Plasmalyte group was 7.41, 7.41, and 7.43 versus 7.39, 7.38, and 7.40 in the lactated Ringer's group, respectively. (Figure 2)

When comparing pH values between groups, pH values differed between groups at the first (p<0.001) and second (p<0.001) hours of infusion, although there was no significant difference between groups in the initial blood samples. In the first hour of infusion, this pH difference was more significant between the NS and Plasmalyte groups (p=0.001) than it was between the Plasmalyte and lactated Ringer's groups (p=0.008). In the second hour of infusion, there was no significant difference in pH between the NS and lactated Ringer's groups (p=0.283) or the lactated Ringer's and Plasmalyte groups (p=0.071). However, pH difference was much more significant between NS and Plasmalyte groups (p<0.001) in the second hour of infusion. The pH changes in each group are shown in Table 3.

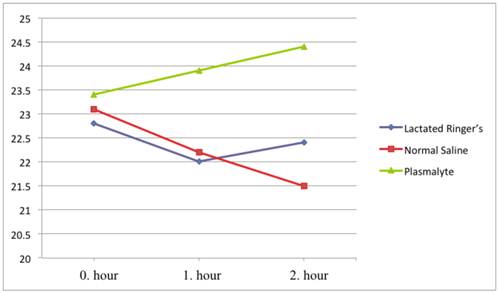

Bicarbonate levels were also in the physiological range (22-26 mM/L) in all groups. Bicarbonate levels decreased in the NS group (average values 23.1, 22.2, and 21.5 mM/L) and increased in the Plasmalyte group (average values 23.4, 23.9, and 24.4 mM/L) at 0, 1, and 2 hours, respectively. There was a significant difference in bicarbonate level between the NS and Plasmalyte groups at the first and second hours of infusion (p=0.002 and p<0.001, respectively). (Figure 3) There were no significant changes in potassium, sodium, or chloride levels during the study (Table 3). We had similar baseline values and responses for hemodynamic parameters responses in all groups. Mean arterial pressure and heart rate parameters were presented in Table 4.

Patient flow chart.

pH values over time.

Bicarbonate levels over time.

Composition of Solutions and Normal Blood Plasma (mM/L).

| Sodium | Potassium | Chloride | Lactate | Calcium | Magnesium | Bicarbonate | Osmolarity | pH | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal Saline | 154 | 154 | 308 mOsm/L | 5 | |||||

| Lactated Ringer's | 130 | 4 | 115 | 28 | 3 | 273 mOsm/L | 6.5 | ||

| Plasmalyte | 140 | 5 | 98 | 3 | 27 (acetate) 23 (gluconate) | 294 mOsm/L | 5 | ||

| Normal blood plasma | 134-146 | 3.4-5 | 98-108 | 2.25-2.65 | 0.7-1.1 | 22-32 | 290 mOsm/L | 7.4 |

Patient demographics.

| Lactated Ringer's | Normal Saline | Plasmalyte | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender M/F (n) | 15/15 | 16/14 | 14/16 |

| Age (year) | 43.8 ± 22.2 | 53.3 ± 18.4 | 48.8 ± 19.7 |

| Diagnosis | |||

| AGE | 18 (% 20) | 19 (% 21.1) | 20 (% 22.2) |

| DWI | 12 (% 13.2) | 11 (% 12.1) | 10 (% 11) |

| Vomiting | 2 (% 6.6) | 2 (% 6.6) | 2 (% 6.6) |

AGE: Acute gastroenteritis, DWI: Decreased water intake.

Changes in metabolic parameters between groups.

| Lactated Ringer's | Normal Saline | Plasmalyte | p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | ||||||

| 0. hour | 7.396±0.049 | 7.406±0.065 | 7.410±0.041 | 0.580 | ||

| 1. hour | 7.387±0.035 | 7.372±0.043 | 7.418±0.039 | <0.001 | ||

| 2. hour | 7.408±0.043 | 7.365±0.055 | 7.434±0.032 | <0.001 | ||

| Bicarbonate (mM/L) | ||||||

| 0. hour | 22.8±2.3 | 23.1±2.3 | 23.4±1.7 | 0.896 | ||

| 1. hour | 22.0± 2.5 | 22.2±2.4 | 23.9±1.7 | 0.002 | ||

| 2. hour | 22.4±2.2 | 21.5±2.3 | 24.4±2.0 | <0.001 | ||

| Sodium (mM/L) | ||||||

| 0. hour | 141.3±3.7 | 140.0±3.7 | 141.5±2.6 | 0.197 | ||

| 1. hour | 141.0±3.6 | 140.6±2.9 | 141.6±2.8 | 0.451 | ||

| 2. hour | 140.6±3.4 | 141.5±3.4 | 141.8±2.6 | 0.301 | ||

| Potassium (mM/L) | ||||||

| 0. hour | 3.8±0.5 | 3.7±0.6 | 3.7±0.4 | 0.948 | ||

| 1. hour | 3.5±0.6 | 3.5±0.6 | 3.6±0.6 | 0.516 | ||

| 2. hour | 3.5±0.5 | 3.5±0.6 | 3.6±0.4 | 0.491 | ||

| Chloride (mM/L) | ||||||

| 0. hour | 98.4±3.5 | 98.7±3.3 | 100.5±2.6 | 0.026 | ||

| 1. hour | 100.7±3.6 | 101.6±3.4 | 101.4±3.6 | 0.246 | ||

| 2. hour | 101.0±2.5 | 102.8±3.9 | 101.1±3.0 | 0.051 | ||

Changes in hemodynamic parameters between groups.

| Mean Arterial Pressure | Moderate dehydration | Severe dehydration | |

| Normal Saline | 0. hour | 71.21±9.69 | 61.21 ± 9.69 |

| 1. hour | 77.69±6.21 | 68.41 ± 8.43 | |

| 2. hour | 82.43±9.44 | 76.92 ± 9.45 | |

| Lactated Ringer's | 0. hour | 72.55±8.95 | 62.55 ± 8.95 |

| 1. hour | 77.76±7.74 | 67.25 ± 7.78 | |

| 2. hour | 81.68±8.84 | 77.24 ± 6.35 | |

| Plasmalyte | 0. hour | 73.18± 9.79 | 63.38 ± 9.79 |

| 1. hour | 78.41±6.21 | 68.18 ± 7.73 | |

| 2. hour | 81.96±9.15 | 76.92 ± 9.45 | |

| Heart Rate | Moderate dehydration | Severe dehydration | |

| Normal Saline | 0. hour | 103.8±8,98 | 131.86±11.24 |

| 1. hour | 95.7±6,68 | 119.64±7.68 | |

| 2. hour | 86.78±6,63 | 98,36±7.71 | |

| Lactated Ringer's | 0. hour | 102.9±8,76 | 132.56±9.14 |

| 1. hour | 93.8±5,49 | 118.87±6.56 | |

| 2. hour | 85.91±5,67 | 100,11±5,48 | |

| Plasmalyte | 0. hour | 103.8±8,98 | 133.27±9.55 |

| 1.hour | 96.34±6,68 | 120.26±7.27 | |

| 2. hour | 87.13±6,63 | 99,68±6.42 | |

DISCUSSION

Our study demonstrates that rapidly infused crystalloid solutions, including NS, lactated Ringer's, and Plasmalyte, have no significant effect on acid-base status. However, there was a significant tendency to lower pH values when using NS, in contrast to Plasmalyte and lactated Ringer's. These findings are consistent with other studies that have shown that large volumes of NS solutions cause acidosis [2-4].

Scheingraber et al. compared the effects of NS with lactated Ringer's in 24 patients who were undergoing major intra-abdominal gynecological surgery, noting that infusion of NS at 30 ml/kg/h, but not lactated Ringer's solution, caused metabolic acidosis with hyperchloremia. In another study, Hadimioglu et al. observed hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis in patients who received NS while undergoing renal transplantation. In the same study, the authors suggested that hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis is related to renal impairment, and that NS infusions exacerbate acidosis [6]. In a similar study, O'Malley et al. examined 51 patients who were undergoing renal transplantation, noting metabolic acidosis in 8 of 26 patients who received NS versus 0 patients who were given lactated Ringer's [7].

In contrast to other studies, all pH values in our patients were within physiological limits (7.35-7.45), which might be attributed to differences in patient populations and infusion rates. Our patients had no previous metabolic disturbances such as renal failure, and the selected infusion rate (20 ml/kg/h) was lower than in other studies (30-50 ml/kg/h). These findings suggest that underlying metabolic disturbances in patients should be considered before fluid is administered in the ED. In patients with acidosis, lactated Ringer's or Plasmalyte might be a better alternative to NS, and the infusion rate should be lower in these patients.

One limitation of our study was the relatively brief observation period. We limited the observation period to 120 minutes, and no follow-up was performed, which might have prevented us from detecting late effects of crystalloid fluids.

In conclusion, rapidly infused crystalloid solutions, including NS, lactated Ringer's, and Plasmalyte, have no significant effect on acid-base status and can be used safely to treat dehydrated patients in the emergency department. However, NS can effect acidosis, which might be significant in patients who have underlying metabolic disturbances—an issue that should be considered before administering fluids in the ED.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

References

1. Tintinalli's Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide, 7e; 2011. Tintinalli JE, Stapczynski JS, Cline DM, Ma OJ, Cydulka RK, Meckler GD. http://www.accessmedicine.com/content.aspx?aID=6358094

2. Scheingraber S. et al. Rapid saline infusion produces hyperchloremic acidosis in patients undergoing gynecologic surgery. Anesthesiology. 1999;90(5):1265-70

3. McFarlane C, Lee A. A comparison of Plasmalyte 148 and 0.9% saline for intra-operative fluid replacement. Anaesthesia. 1994;49(9):779-81

4. Prough D.S, Bidani A. Hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis is a predictable consequence of intraoperative infusion of 0.9% saline. Anesthesiology. 1999;90(5):1247-9

5. Gunnerson K.J. Clinical review: the meaning of acid-base abnormalities in the intensive care unit part I - epidemiology. Crit Care. 2005;9(5):508-16

6. Hadimioglu N. et al. The effect of different crystalloid solutions on acid-base balance and early kidney function after kidney transplantation. Anesth Analg. 2008;107(1):264-9

7. O'Malley C.M, Frumento R.J, Bennett-Guerrero E. Intravenous fluid therapy in renal transplant recipients: results of a US survey. Transplant Proc. 2002;34(8):3142-5

Author contact

![]() Corresponding author: Hakan Hasman, MD. Department of Emergency Medicine, Gulhane Military Medical Academy, GATA Acil Tip Anabilim Dali, Etlik, Ankara, Turkey 06010. 0090-312-304-3080; hakan_hascom.

Corresponding author: Hakan Hasman, MD. Department of Emergency Medicine, Gulhane Military Medical Academy, GATA Acil Tip Anabilim Dali, Etlik, Ankara, Turkey 06010. 0090-312-304-3080; hakan_hascom.

Global reach, higher impact

Global reach, higher impact