Impact Factor

ISSN: 1449-1907

Int J Med Sci 2011; 8(5):424-427. doi:10.7150/ijms.8.424 This issue Cite

Case Report

Placenta Percreta-Induced Uterine Rupture Diagnosed By Laparoscopy in the First Trimester

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, College of Medicine, St. Vincent's Hospital, The Catholic University of Korea, Seoul, Korea

Received 2011-5-16; Accepted 2011-7-6; Published 2011-7-8

Abstract

Spontaneous uterine rupture is lethal in pregnant women. Placenta percreta-induced spontaneous uterine rupture in the first trimester is extremely rare and difficult to diagnose. A 35-year-old pregnant woman, with a history of 2 vaginal deliveries and 2 spontaneous abortions treated by dilatation and curettage, was admitted to the emergency department because of sudden severe abdominal pain; the gestational age as calculated by sonography was 14 weeks. Diagnostic laparoscopy was considered for surgical abdomen and fluid collection that was noted in sonography. During laparoscopy, uterine rupture with massive bleeding was detected; therefore, total abdominal hysterectomy was performed. The patient was discharged without any complications. Pathological analysis of the uterine specimen revealed placenta percreta to be the cause of the rupture. Uterine rupture should be considered in the differential diagnosis in all pregnant women who present with acute abdomen, show fluid collection in the peritoneal cavity. In addition, we recommend laparoscopy for the investigation of acute abdomen with unclear diagnosis in the first trimester of pregnancy.

Keywords: pregnancy, first trimester, uterine rupture, laparoscopy

Introduction

Uterine rupture due to placenta percreta is very rare, with an incidence of 1 in 5,000 pregnant women [1]. It often occurs in patients with a history of Cesarean section [2].

Based on our review of medical literature, spontaneous uterine ruptures mainly occur during the second or third trimester; its occurrence in the first trimester is extremely rare and in such cases, has a catastrophic outcome due to massive hemorrhage [2, 3].

Here, we report the case of a pregnant woman who suffered from a spontaneous uterine rupture due to placenta percreta at 14 weeks of gestation.

Case Report

A 35-year-old pregnant woman (gravida 5, para 2), with a history of 2 vaginal term deliveries and 2 spontaneous abortions treated by dilatation and curettage, was admitted to the emergency department because of sudden severe abdominal pain. At admission, the gestational age was calculated to be 14 weeks by sonography (Fig. 1); she had not received any antenatal care. During physical examination, abdominal tenderness was noted; in addition, her blood pressure was 110/60 mm Hg; heart rate, 98 beats/min; and body temperature, 36.1°C.

Ultrasound examination revealed moderate accumulation of free fluid in the peritoneal cavity. In addition, the placenta was located at the upper anterior uterine wall, the fetal heart rate was 171 beats/min, and uterine contractions were absent. Laboratory analysis showed a hemoglobin level of 10.3 g/dl and an elevated white blood cell count of 17550 cells/mm3. Because the pregnancy was intrauterine and not otherwise, our initial clinical impression was appendicitis; however, in the absence of fever, the diagnosis of appendicitis could not be confirmed. To diagnose the cause of continuous severe abdominal pain, we decided to conduct diagnostic laparoscopy to exclude appendicitis, cholecystitis, and peritonitis.

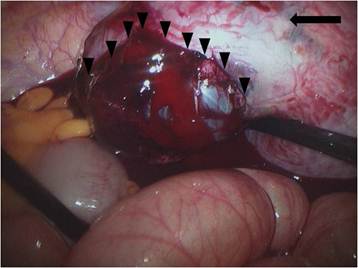

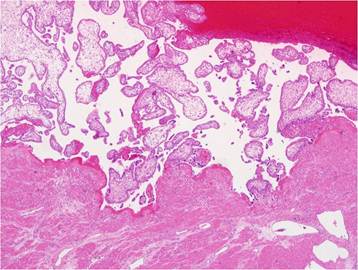

At the time of laparoscopy, 800 ml of fresh blood and 0.5-cm fundal defect of the uterus were noted (Fig. 2). The placenta and amniotic membrane were seen bulging spontaneously and slowly, and the uterine defect was gradually enlarging, with its size increased to 3 cm as last noted. Because the amount of blood in the ruptured area increased rapidly, we decided to convert laparoscopy to laparotomy. At the beginning of the laparotomy, the fetus was spontaneously delivered through the ruptured site. We preferred total abdominal hysterectomy to conservative management because of the large, fragile, and thin uterine wall with abundant blood vessels on the surface. The total estimated blood loss during the operation was 1000 ml; the patient was transfused 4 units of packed red blood cells and 2 units of fresh frozen plasma. Her recovery was uneventful, and she was discharged on postoperative day 6. The final pathological examination revealed that the chorionic villi had invaded the entire myometrium up to the serosa, confirming the diagnosis of placenta percreta (Fig. 3). The length of the fetus measured from the crown to rump was 9.0 cm, and fetal weight was 69.3 g; these measurements were consistent with 14 weeks of gestation.

Ultrasound examination showing intrauterine pregnancy at 14 weeks gestation.

Ruptured uterus and bulging amnion and placenta enlarging the ruptured hole. arrow: uterine fundus; arrow head: amnion and placenta.

Chorionic villi in the myometrium of uterus, which explains the placenta percreta, are noted at microscopic field (x 40).

Discussion

Placenta percreta-induced uterine rupture in the first trimester in our patient may be attributed to the previous dilatation and curettage. Placenta percreta is the rarest form of placental abnormalities, with a 5-7% incidence among all placenta accreta cases [4]. In placenta percreta, the decidua basalis is partially or completely absent, and the chorionic villi invade the entire myometrium up to the serosa [5].

Uterine rupture caused by placenta percreta mainly occurs during the later period of pregnancy, with very few reports of its occurrence during the first trimester [3]. However, it has been reported to occur at as early as 9 weeks of gestation [6]. In most cases of uterine ruptures that occur during delivery, the affected site is the lower uterine segment; however, in cases of uterine rupture during the first trimester, the site commonly affected is the fundus, as noted in our patient [7]. The uterine ruptures in the first trimester were summarized in Table 1 [3, 6, 8-11].

The most common risk factor for uterine rupture is a history of Cesarean section. Other risk factors include placenta previa; high parity; advanced maternal age; and a history of endometriosis, dilatation and curettage, myomectomy, or irradiation [12, 13]. In the present case, the patient had no history of Cesarean section but had 2 spontaneous abortions treated by dilatation and curettage.

Fluid collection during pregnancy is sometimes considered insignificant if the vital signs are stable; however, fluid collection in the peritoneal cavity along with acute abdomen should be evaluated for the differential diagnosis such as appendicitis and hemoperitoneum. The gradual increase in the size of the uterus with advancing pregnancy can cause a delay in the diagnosis and appropriate treatment. The first laparoscopic surgery during pregnancy was cholecystectomy, performed in 1991 [14]. Thereafter, laparoscopy has been widely used in pregnant women for the differential diagnosis of acute abdomen such as appendicitis, cholecystitis, or adnexal masses [15]. In addition, laparoscopic surgery during pregnancy is regarded safe [14, 16]. Hence, in vague and emergent conditions, such as in the case of our patient, laparoscopy can be helpful for the early diagnosis of hemoperitoneum due to uterine rupture.

In general, the area of placenta percreta-induced uterine rupture exhibits more vascularization than the site of previous scar-induced rupture; therefore, uterine rupture caused by placenta percreta can be more dangerous than that caused by a previous scar [13]. Total hysterectomy is considered in the case of life-threatening severe bleeding or insufficient hemostasis [13, 17].

Conservative treatments for placenta percreta-induced uterine rupture have been reported, such as uterine curettage along with packing, adjuvant chemotherapy, and bilateral uterine vessel occlusion [18, 19]. However, considering a 4-fold mortality rate associated with these conservative treatments as compared to hysterectomy, the latter is usually preferred in an emergent situation [5].

In conclusion, this report highlights the significance of a history of spontaneous abortion treated by dilatation and curettage in uterine rupture caused by placenta percreta. Uterine rupture should be considered in the differential diagnosis in all pregnant women who present with acute abdomen, show fluid collection in the peritoneal cavity, and have specific risk factors, even during the first trimester. In addition, we recommend laparoscopy for the investigation of acute abdomen with unclear diagnosis in the first trimester of pregnancy.

The summary of uterine ruptures in the first trimester [3, 6, 8-11].

| Authors | Year | Gestational age (weeks) | Ruptured site of uterus | Risk factors | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Helkjaer et al | 1982 | 11 | Low segment | Cesarean section | Primary closure |

| Singh et al | 2000 | 10 | Fundus | Multiparity | Hysterectomy |

| Matsuo et al | 2004 | 10 | Low segment | Cesarean section | Primary closure |

| Park et al | 2005 | 10 | Fundus | Multiparity | Primary closure |

| Dabulis et al | 2007 | 9 | Low segment | Cesarean section, dilatation and curettage | Hysterectomy |

| Ismail et al | 2007 | 6 | Low segment | Cesarean section | Methotrexate |

Conflict of Interest

The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

References

1. Gardeil F, Daly S, Turner MJ. Uterine rupture in pregnancy reviewed. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1994;56:107-10

2. Turner MJ. Uterine rupture. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2002;16:69-79

3. Park YJ, Ryu KY, Lee JI, Park MI. Spontaneous uterine rupture in the first trimester: a case report. J Korean Med Sci. 2005;20:1079-81

4. Hudon L, Belfort MA, Broome DR. Diagnosis and management of placenta percreta: a review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1998;53:509-17

5. Moriya M, Kusaka H, Shimizu K, Toyoda N. Spontaneous rupture of the uterus caused by placenta percreta at 28 weeks of gestation: a case report. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 1998;24:211-4

6. Dabulis SA, McGuirk TD. An unusual case of hemoperitoneum: uterine rupture at 9 weeks gestational age. J Emerg Med. 2007;33:285-7

7. Schrinsky DC, Benson RC. Rupture of the pregnant uterus: a review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1978;33:217-32

8. Helkjaer PE, Petersen PL. [Rupture of the uterus in the 11th week of pregnancy]. Ugeskr Laeger. 1982;144:3836-7

9. Singh A, Jain S. Spontaneous rupture of unscarred uterus in early pregnancy--a rare entity. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2000;79:431-2

10. Matsuo K, Shimoya K, Shinkai T. et al. Uterine rupture of cesarean scar related to spontaneous abortion in the first trimester. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2004;30:34-6

11. Ismail SI, Toon PG. First trimester rupture of previous caesarean section scar. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2007;27:202-4

12. Smith L, Mueller P. Abdominal pain and hemoperitoneum in the gravid patient: a case report of placenta percreta. Am J Emerg Med. 1996;14:45-7

13. Miller DA, Chollet JA, Goodwin TM. Clinical risk factors for placenta previa-placenta accreta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;177:210-4

14. Chohan L, Kilpatrick CC. Laparoscopy in pregnancy: a literature review. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2009;52:557-69

15. Kilpatrick CC, Monga M. Approach to the acute abdomen in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2007;34:389-402

16. Al-Fozan H, Tulandi T. Safety and risks of laparoscopy in pregnancy. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2002;14:375-9

17. Medel JM, Mateo SC, Conde CR, Cabistany Esque AC, Rios Mitchell MJ. Spontaneous uterine rupture caused by placenta percreta at 18 weeks' gestation after in vitro fertilization. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2010;36:170-3

18. Legro RS, Price FV, Hill LM, Caritis SN. Nonsurgical management of placenta percreta: a case report. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;83:847-9

19. Wang LM, Wang PH, Chen CL, Au HK, Yen YK, Liu WM. Uterine preservation in a woman with spontaneous uterine rupture secondary to placenta percreta on the posterior wall: a case report. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2009;35:379-84

Author contact

![]() Corresponding author: Sung Jong Lee, Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, St. Vincent's Hospital, 93-6 Ji-dong, Paldal-gu, Suwon, Kyeonggi 442-723, Korea Tel: 82-31-249-7300; Fax: 82-31-254-7481; E-mail: orlandoac.kr

Corresponding author: Sung Jong Lee, Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, St. Vincent's Hospital, 93-6 Ji-dong, Paldal-gu, Suwon, Kyeonggi 442-723, Korea Tel: 82-31-249-7300; Fax: 82-31-254-7481; E-mail: orlandoac.kr

Global reach, higher impact

Global reach, higher impact