Impact Factor

ISSN: 1449-1907

Int J Med Sci 2011; 8(4):345-350. doi:10.7150/ijms.8.345 This issue Cite

Case Report

Foramen Magnum Arachnoid Cyst Induces Compression of the Spinal Cord and Syringomyelia: Case Report and Literature Review

1. Department of Neurosurgery, First Hospital of Jilin University, Changchun, 130021, P. R. China

2. Department of Radiology, First Hospital of Jilin University, Changchun, 130021, P. R. China

3. Department of Pathology, First Hospital of Jilin University, Changchun, 130021, P. R. China

* Haiyan Huang, Yunqian Li and Kan Xu contributed equally to the work.

Received 2011-4-21; Accepted 2011-5-16; Published 2011-5-27

Abstract

It is very rare that a foramen magnum arachnoid cyst induces compression of the spinal cord and syringomyelia, and currently there are few treatment experiences available. Here we reported the case of a 43-year-old male patient who admitted to the hospital due to weakness and numbness of all 4 limbs, with difficulty in urination and bowel movement. MRI revealed a foramen magnum arachnoid cyst with associated syringomyelia. Posterior fossa decompression and arachnoid cyst excision were performed. Decompression was fully undertaken during surgery; however, only the posterior wall of the arachnoid cyst was excised, because it was almost impossible to remove the whole arachnoid cyst due to toughness of the cyst and tight adhesion to the spinal cord. Three months after the surgery, MRI showed a reduction in the size of the arachnoid cyst but syrinx still remained. Despite this, the symptoms of the patient were obviously improved compared to before surgery. Thus, for the treatment of foramen magnum arachnoid cyst with compression of the spinal cord and syringomyelia, if the arachnoid cyst could not be completely excised, excision should be performed as much as possible with complete decompression of the posterior fossa, which could result in a satisfying outcome.

Keywords: foramen magnum, arachnoid cyst, syringomyelia.

Introduction

The commonest type of arachnoid cyst that causes compression of the spinal cord and development of syringomyelia is the Chiari malformation type I [1]. Other types of arachnoid cysts can occur as an occupied lesion in the posterior fossa and in Dandy-Walker syndrome [2-10]. Occasionally, a posterior fossa arachnoid cyst can induce compression of the spinal cord and development of syringomyelia [11,12]. Common features of these lesions are secondary cerebellar tonsillar herniation with syringomyelia due to mass effect, and the lesions cross most areas of the foramen magnum. It is very rare that a foramen magnum arachnoid cyst directly compresses the spinal cord and develops syringomyelia. Here we reported a rare case of foramen magnum arachnoid cyst with occupying only small area of the posterior fossa. We performed surgery on this patient. Meanwhile, we undertook a literature review on this topic as well, in order to provide better understanding and relate our experience in the diagnosis and treatment of foramen magnum arachnoid cyst.

Case report

A male patient, 43 years old, was admitted to First Hospital of Jilin University in October 2009 due to worsening weakness and numbness of all four limbs over the previous 6 years, and urination and bowel problems for one year. The patient had a history of tuberculous meningitis at 22 years of age with no sequelae after treatment. Physical examinations showed diminished superficial sensation in the bilateral upper limbs and trunk above the umbilicus, muscle wasting of the bilateral thenar and upper limbs, grade III muscle power of the upper and lower limbs, reduced tendon reflex, negative Babinski's sign, reduced cremasteric and anal reflexes. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed 5 cm of cystic lesion across the posterior part of the foramen magnum. The lesion in T1WI imaging appeared as a low signal, and as a high signal in T2WI imaging. The cerebellar tonsil was compressed upwards, the pons and cervical spinal cord appeared notch-like due to the compression of the cyst. The spinal cord was thickened from the pons to the thoracic spinal cord T10, and a syrinx was seen in the spinal cord with a low T1W1 signal and a high T2WI signal. The size of the supratentorial ventricular system was normal (Figure 1). Based on history and physical and MRI examinations, we diagnosed the lesion as a foramen magnum arachnoid cyst with syringomyelia.

Presurgical MRI examinations. A: Head MRI revealing a normal ventricle. B: MRI showing a cystic lesion across the foramen magnum. T2WI imaging showed the lesion as a high signal (arrow). C: T1WI imaging showed the lesion as a lower signal; the cerebellar tonsil was compressed and moved upwards. The pons and cervical spinal cord anterior to the lesion appeared notch-like (arrow). D: MRI showed the spinal cord thickened from the pons to T10; a syrinx can be seen. T2WI imaging appeared as a high signal (arrow).

Decompression of the posterior fossa and excision of the arachnoid cyst were then surgically performed. A straight median incision was made on the skull via the posterior temporal route. The occipital squama was cut off and the posterior edge of the foramen magnum and posterior arch of the atlas were then fully decompressed, followed by opening the dura mater. A blister-like cyst was seen to be located in the pons and posterior part of the cervical spinal cord. The cerebellar tonsil was compressed and pushed upwards. After opening the cyst, it was seen that there were multiple compartments of a hard texture within the cyst. The cyst tightly adhered to the cerebrum, pons and cervical spinal cord. The compartments were then separated and the posterior wall of the cyst was excised to break down the cystic structure. The tissue was sent for pathological examination. However, the cyst was not completely excised due to the tight adhesion of the anterior wall of the cyst to the cervical spinal cord. A suture wound closure of the dura mater was performed using artificial mesh repair.

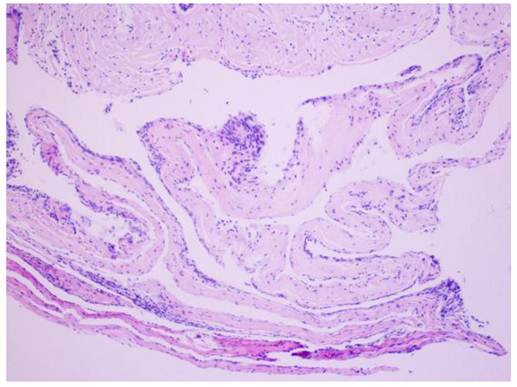

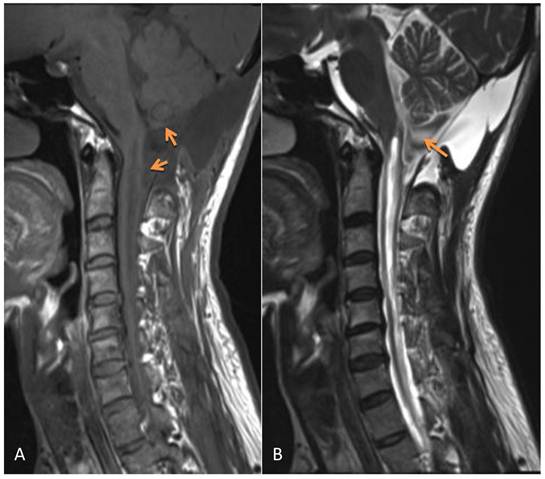

The postoperative symptoms were slightly improved compared to pre-surgery. The results of pathological examination showed that the wall of the cyst was composed of fibrous tissue but without epithelial cells; the diagnosis of arachnoid cyst was made (Figure 2). During three months of follow-up, the condition of this patient continued to improve with normal urination and bowel function and good daily self-management. Physical examinations showed that superficial sensation was gradually diminished and muscle power of upper and lower limbs increased to grade V. Tendon reflex was normal, however, there was no improvement in muscle wasting. MRI re-examination showed that the arachnoid cyst still remained, however, its size appeared slightly smaller than that before surgery. Although the compression on the cerebellar tonsil, pons and cervical spinal cord was reduced, the size of the syrinx was still the same as before surgery (Figure 3).

Results of pathology. H&E staining showing fibrous tissue on the wall of the cyst, and no epithelial cells were observed; arachnoid cyst was diagnosed. Magnification: ×200.

MRI 3 months after surgery shows the remaining arachnoid cyst (which was slightly smaller than before surgery), the compression on the cerebellar tonsil, the reduced pons and cervical spinal cord. However, the syrinx was the same as presurgery. A: T1WI; B: T2WI.

Discussion

There are two causes of compression of the spinal cord and syringomyelia induced by a foramen magnum lesion. One is a primary Chiari malformation type I, in which the cerebellar tonsil herniates into the foramen magnum and spinal canal to compress the spinal cord, consequently causing blockage of the spinal canal and the stoppage of cerebral spinal flow, leading to syringomyelia [13,14]. The other is an occupied lesion in the posterior fossa pushing the cerebellar tonsil downwards to develop a malformation, which is similar to Chiari malformation type I. Examples of foramen magnum lesions reported in the literature include Klekamp et al. [2] who reported 3 cases of posterior fossa tumor in 1995, Bhatoe et al. [3] reported one case of meningioma in the cerebellar tentorium in 2004, Muzumdar et al. [4] in 2006 and Wu et al. [7] in 2010 each reported one case of pilocytic astrocytoma in the posterior fossa, EI Hassani et al. [5] reported one case of cerebellar vermis medulloblastoma in 2009, and Suyama et al. [6] reported one case of a dermoid tumor in the cerebellum in 2009. These cases were all due to secondary cerebellar tonsillar herniation associated with syringomyelia, induced by an occupied lesion in the posterior fossa. The only large scale case study has been done by Tachibana et al. [8], who in 1995 showed that in 164 cases of posterior fossa tumor, twenty-four (14.6%) had secondary cerebellar tonsillar herniation. Of these, only 5 cases (20.8%) were complicated with syringomyelia. Apart from the tumors mentioned above, some arachnoid cysts in the posterior fossa also cause similar changes to that in Dandy-Walker syndrome[9,10,15,16].

Most posterior fossa arachnoid cysts result in cerebellar tonsillar herniation, consequently leading to compression of the spinal cord and syringomyelia due to the effect of the mass [15-18]. It is extremely rare for the foramen magnum arachnoid cyst to directly compress the spinal cord and develop syringomyelia. In 2000, Jain et al. [19] reported one case of a giant posterior fossa arachnoid cyst extending into the spinal canal to compress the spinal cord and develop syringomyelia; Kiran et al. [20] in 2010 also reported such a case. Although the case we reported here had similar features to these two cases, differences exist. The cyst in our case did not occupy most areas of the posterior fossa as these two cases did, instead it extended across the foramen magnum into the spinal canal at the level of the atlas. Thus, the lesion in our case was extremely rare, and it is also possible one of the reasons that the syrinx did not shrink considerably upon decompression of the foramen magnum as reported previously by most of case studies.

With the report of this case we also did a literature review in order to have a better understanding of arachnoid cysts. Currently, the noncogenital causes of arachnoid cysts are unclear. It has been hypothesized that infection, trauma, circulation of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and/or changes in CSF pressure contribute to the formation of arachnoid cysts. It is generally accepted that arachnoid cyst may be a congenital malformation due to the dynamic CSF pressure changes during development, leading to tearing of the arachnoid mater [21-23]. The patient we reported here had a history of tuberculous meningitis at 22 years of age; he recovered after treatment. Although arachnoid cyst associated with tuberculous meningitis is uncommon, such cases have been reported. Van et al. [24] in 1990 reported one case of acquired spinal cord arachnoid cyst after tuberculous meningitis. Lolge et al. [25] in 2004 also reported two such cases; the cyst in one was located at the anterior part of the foramen magnum. Because it is very difficult to know whether the cyst is congenital or acquired, it is unclear whether tuberculous meningitis was the cause of the foramen magnum arachnoid cyst formation. Nevertheless, whatever the cause the patient had 6 years of clinical presentation and his condition had worsened in the past year. MRI revealed that the arachnoid cyst extended across the forma magnum to compress the spinal cord, and thus surgical treatment was considered. Surgical indications should be considered when an arachnoid cyst becomes progressively enlarged and compresses surrounding blood vessels, leading to corresponding symptoms gradually worsening[26-28]. The features of the present case were considered a suitable standard for surgical indication. Thus, surgical treatment was performed in this case.

There are several types of treatment for arachnoid cyst, including cyst fenestration, cyst-peritoneal shunting and complete or partial excision. The most effective treatment is excision of the whole wall of the cyst to effectively prevent recurrence, particularly posterior fossa tumor [26,29,30]. Posterior fossa arachnoid cyst usually occupies the cerebellopontine angle, a condition from which most experience in its treatment has been obtained. For example, Samii et al.[31] in 1999 reported 12 cases of posterior fossa arachnoid cyst which extended into the cerebellopontine angle. Prognosis in most cases was good after excision of the cysts. However, the location of the cyst in the case we reported here was special and although simple excision can effectively prevent reoccurrence, it was difficult to release the pressure on the spinal cord or relieve syringomyelia due to the pathological changes similar to Chiari malformation type I. Based on the standard treatment of Chiari malformation type I, we thought that sufficient decompression of the posterior fossa and dural suture closure would have a better treatment effect [32-35]. It has been shown that decompression is certainly effective in patients with Chiari malformation type I associated with syringomyelia. Aghakhani et al. [32] reported 157 cases of treatment of Chiari malformation type I. Clinical improvement occurred in 63.06% of these cases, and the percentage of reduction in syrinxes was 90%. Wetjen et al. [33] in 2008 reported 29 cases in which 94% of the patients had improved symptoms. During 3-6 months of follow-up, MRIs revealed a decrease in syrinx size to a varied extent. Heiss et al. [34] in 2010 reported 16 cases of Chiari malformation type I, and syrinxes decreased in 15 patients (94%) after decompression.

The patient we reported here had markedly improved symptoms after decompression treatment. However, MRI demonstrated no reduction in the size of syrinx 3 months after surgery. We consider this to be related to the short follow-up period and incomplete excision of the arachnoid cyst. During surgery the wall of the arachnoid cyst was found to be thick and tough and it adhered tightly to the spinal cord, thus it was not completely excised. Moreover, the thickened arachnoid mater was possibly associated with the patient's tuberculous meningitis 21 years previously. We assume that it was the incomplete excision of the arachnoid cyst that caused a slight reduction in the size of the cyst, and is a possible reason for the insufficient result.

Conclusion

Thus, we think, for the cases of foramen magnum arachnoid cyst with compression of the spinal cord and syringomyelia, even if the arachnoid cyst could not be completely excised, excision should be performed as much as possible with complete decompression of the posterior fossa, which may result in a satisfying outcome.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

References

1. Park YS, Kim DS, Shim KW. et al. Factors contributing improvement of syringomyelia and surgical outcome in type I Chiari malformation. Childs Nerv Syst. 2009;25:453-9

2. Klekamp J, Samii M, Tatagiba M. et al. Syringomyelia in association with tumours of the posterior fossa. Pathophysiological considerations, based on observations on three related cases. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1995;137:38-43

3. Bhatoe HS. Tonsillar herniation and syringomyelia secondary to a posterior fossa tumour. Br J Neurosurg. 2004;18:70-1

4. Muzumdar D, Ventureyra EC. Tonsillar herniation and cervical syringomyelia in association with posterior fossa tumors in children: a case-based update. Childs Nerv Syst. 2006;22:454-9

5. El Hassani Y, Burkhardt K, Delavellle J. et al. Symptomatic syringomyelia occurring as a late complication of posterior fossa medulloblastoma removal in infancy in a boy also suffering from scaphocephaly. Childs Nerv Syst. 2009;25:1633-7

6. Suyama K, Ujifuku K, Hirao T. et al. Symptomatic syringomyelia associated with a dermoid tumor in the posterior fossa. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2009;49:434-7

7. Wu FZ, Fu JH, Chen JY. et al. Teaching NeuroImages: acquired Chiari malformation with syringohydromyelia caused by posterior fossa tumor. Neurology. 2010;75:e59

8. Tachibana S, Harada K, Abe T. et al. Syringomyelia secondary to tonsillar herniation caused by posterior fossa tumors. Surg Neurol. 1995;43:470-475

9. Kasliwal MK, Suri A, Sharma BS. Dandy Walker malformation associated with syringomyelia. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2008Mar;110(3):317-9

10. Richter EO, Pincus DW. Development of syringohydromyelia associated with Dandy-Walker malformation: treatment with cystoperitoneal shunt placement. Case report. J Neurosurg. 2006;104:206-9

11. Bauer AM, Mueller DM, Oró JJ. Arachnoid cyst resulting in tonsillar herniation and syringomyelia in a patient with achondroplasia. Case report. Neurosurg Focus. 2005;19:E14

12. Galarza M, López-Guerrero AL, Martínez-Lage JF. Posterior fossa arachnoid cysts and cerebellar tonsillar descent: short review. Neurosurg Rev. 2010;33:305-14

13. Oldfield EH. Syringomyelia. J Neurosurg. 2001;95:153-155

14. Milhorat TH, Johnson RW, Milhorat RH. et al. Clinicopathological correlations in syringomyelia using axial magnetic resonance imaging. Neurosurgery. 1995;37:206-13

15. Galarza M, López-Guerrero AL, Martínez-Lage JF. Posterior fossa arachnoid cysts and cerebellar tonsillar descent: short review. Neurosurg Rev. 2010;33:305-14

16. Marin SA, Skinner CR, Da Silva VF. Posterior fossa arachnoid cyst associated with Chiari I and syringomyelia. Can J Neurol Sci. 2010;37:273-5

17. Martínez-Lage JF, Almagro MJ, Ros de San Pedro J. et al. Regression of syringomyelia and tonsillar herniation after posterior fossa arachnoid cyst excision. Case report and literature review. Neurocirugia (Astur). 2007;18:227-31

18. Martínez-Lage JF, Ruiz-Espejo A, Guillén-Navarro E. et al. Posterior fossa arachnoid cyst, tonsillar herniation, and syringomyelia in trichorhinophalangeal syndrome Type I. J Neurosurg. 2008;109:746-50

19. Jain R, Sawlani V, Phadke R. et al. Retrocerebellar arachnoid cyst with syringomyelia: a case report. Neurol India. 2000;48:81-3

20. Kiran NA, Kasliwal MK, Suri A. et al. Giant posterior fossa arachnoid cyst associated with syringomyelia. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2010;112:454-5

21. Brooks ML, Mayer DP, Sataloff RT. et al. Intracanalicular arachnoid cyst mimicking acoustic neuroma: CT and MRI. Comput Med Imaging Graph. 1992;16:283-5

22. Inoue T, Matsushima T, Fukui M. et al. Immunohistochemical study of intracranial cysts. Neurosurgery. 1988;23:576-81

23. Rengachary SS, Watanabe I. Ultrastructure and pathogenesis of intracranial arachnoid cysts. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1981;40:61-83

24. Van Paesschen W, Van den Kerchove M, Appel B. et al. Arachnoiditis ossificans with arachnoid cyst after cranial tuberculous meningitis. Neurology. 1990;40:714-6

25. Lolge S, Chawla A, Shah J. et al. MRI of spinal intradural arachnoid cyst formation following tuberculous meningitis. Br J Radiol. 2004;77:681-4

26. Ciricillo SF, Cogen PH, Harsh GR. et al. Intracranial arachnoid cysts in children. A comparison of the effects of fenestration and shunting. J Neurosurg. 1991;74:230-5

27. Haberkamp TJ, Monsell EM, House WF. et al. Diagnosis and treatment of arachnoid cysts of the posterior fossa. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1990;103:610-4

28. Jallo GI, Woo HH, Meshki C. et al. Arachnoid cysts of the cerebellopontine angle: diagnosis and surgery. Neurosurgery. 1997;40:31-7

29. Lange M, Oeckler R. Results of surgical treatment in patients with arachnoid cysts. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1987;87(3-4):99-104

30. Yokota J, Imai H, Okuda O. et al. Inverted Bruns' nystagmus in arachnoid cysts of the cerebellopontine angle. Eur Neurol. 1993;33:62-4

31. Samii M, Carvalho GA, Schuhmann MU. et al. Arachnoid cysts of the posterior fossa. Surg Neurol. 1999;51:376-82

32. Aghakhani N, Parker F, David P. et al. Long-term follow-up of Chiari-related syringomyelia in adults: analysis of 157 surgically treated cases. Neurosurgery. 2009;64:308-15

33. Wetjen NM, Heiss JD, Oldfield EH. Time course of syringomyelia resolution following decompression of Chiari malformation Type I. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2008;1:118-23

34. Heiss JD, Suffredini G, Smith R. et al. Pathophysiology of persistent syringomyelia after decompressive craniocervical surgery. Clinical article. J Neurosurg Spine. 2010;13:729-42

35. Spena G, Bernucci C, Garbossa D. et al. Clinical and radiological outcome of craniocervical osteo-dural decompression for Chiari I-associated syringomyelia. Neurosurg Rev. 2010;33:297-303

Author contact

![]() Corresponding author: Jinlu Yu, +86043188782331, E-mail: jinluyucom

Corresponding author: Jinlu Yu, +86043188782331, E-mail: jinluyucom

Global reach, higher impact

Global reach, higher impact