Impact Factor

ISSN: 1449-1907

Int J Med Sci 2011; 8(1):84-87. doi:10.7150/ijms.8.84 This issue Cite

Case Report

Bronchial Anthracofibrosis Case with Endobronchial Tuberculosis

1. Department of Pulmonary Medicine, Konya Education and Research Hospital, Konya, Turkey;

2. Department of Pulmonary Medicine, Meram Medical Faculty, Selcuk University, Konya, Turkey;

3. Department of Diagnostic Radiology, George-August-University Hospital, Göttingen, Germany.

Received 2010-8-18; Accepted 2011-1-11; Published 2011-1-11

Abstract

We reported a case with bronchial anthracofibrosis and endobronchial tuberculosis. Our case demonstrated this possible correlation between anthracofibrosis and endobronchial tuberculosis. We showed this correlation visually and microbiologically.

Keywords: Anthracofibrosis, endobronchial tuberculosis, inflammatory bronchial stenosis

Introduction

Endobronchial anthracofibrosis is a disease diagnosed by endobronchial endoscopy findings of dark pigmentation (anthracosis) on the bronchial mucosa in patients without coniosis or a history of smoking that is associated with bronchial stenosis or an obstruction due to fibrosis in the same area (1-3). The term anthracofibrosis has more recently been coined to describe a distinct entity of inflammatory bronchial stenosis with overlying anthracotic mucosa (1, 4).

Endobronchial tuberculosis (EBTB) is defined as tuberculous infection of the tracheobronchial tree with microbial and histopathological evidence (5). It is present in 10-40% of patients with active pulmonary tuberculosis, and more than 90% of the patients with EBTB have some degree of bronchial stenosis (6). It may present as a troublesome therapeutic problem due to its sequel of cicatricial stenosis.

In this case report, we would like to report a case with anthracofibrosis and endobronchial tuberculosis in order to mention the problems that may arise while making the diagnosis of tuberculosis as both problems cause endobronchial stenosis.

Case

Sixty three years old, female case who has been followed for three years with the diagnosis of anthracofibrosis admitted to our hospital with the complaints of cough, fever and dyspnea. She has been living in rural part of the city and had indoor cooking/heating smoke exposure history for at least forty years.

Complete blood count was performed with Cell-Dyn 3700 analyzer (Abbott, USA). This blood examination revealed elevated WBC count of 20.600/µL, hemoglobin concentration of 13.1 g/dl, hematocrit level of 42.1 and platelet count of 501.000/µL. Sputum examination for acid-fast bacilli (AFB) was negative and CRP was 98.9 mg/dl. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 64 mm/ hour.

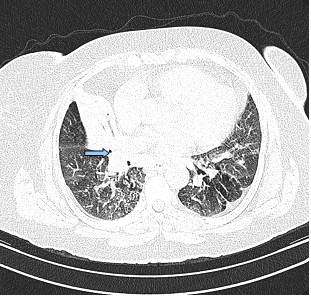

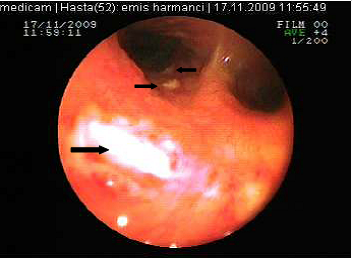

The posterior anterior chest graphy showed consolidation area in right paracardiac region. The high resolution thorax spiral computed tomography (HRCT) obtained on admission revealed consolidation area and atelectasis in right middle lobe (Figure 1). Flexible bronchoscopy (FOB) application was planned to the patient. FOB examination revealed hypervascularisation, hyperemia, deformed bronchial trees and these findings were similar to previous FOB findings. Previous FOB examination has been done to examine middle lobe atelectasis. However, white necrotic lesions were observed in orifice of the middle lobe and at entry of main right bronchus and intermediate bronchus differently from previous bronchoscopic examination (Figure 2, 4). Biopsy from necrotic lesions and bronchus lavage were performed. Histological and cytological findings of material were benign. Microscopic findings of biopsy revealed infection that consists of concentrated lymphoplasmocytes, regular cartilage, and a few polymorph nuclear leucocytes. No AFB was performed on the biopsy specimen. AFB was negative in bronchus lavage; however, mycobacterial cultivation was positive revealing mycobacterium tuberculosis and sensitive to all major tuberculosis agents.

Treatment and clinical course

Tuberculosis treatment was initiated with isoniazid with a daily dose of 300 mg, rifampicin 600 mg, ethambutol 1500 mg, pyrazinamide1500 mg and these doses were planned to be continued for further 6 months. Clinical remission started after two weeks of the treatment period. Control sputum samples were obtained and control culture analysis was performed at the end of two months therapy. Both of these were negative for AFB. We observed significant clinical and radiological remission at the end of three months of this treatment period. Control FOB examination performed in the sixth month of the therapy demonstrated that the white colored necrotic lesions disappeared completely and significant improvement was observed (Figure 3 and Figure 5, respectively).

Consolidation area and atelectasis in right middle lobe of the patient

Necrosis and anthracosis in orophis of the middle lobe

Necrotic lesions were disappeared at the end of six months treatment

White colored necrosis area in distal trachea and entry of right main bronchus

Necrotic lesions were disappeared at the end of six months treatment

Discussion

Anthracosis is black pigment discoloration of bronchi, which can cause bronchial destruction and deformity. Long term exposure of indoor cooking/heating smoke and tuberculosis are the important causes of anthracosis. In our country in the rural areas wood, animal dung and crop residues are used as fuel. By winter exposure to inhouse smoke is more obvious because of the usage of open ovens for cooking or heating in poorly ventilated confined spaces at least once a week but more often every day. Our patient had indoor cooking/heating smoke exposure history and this may be the cause of bronchial anthracosis in this case. Also, previous case series have suggested a possible correlation between anthracofibrosis with TB (1, 2, 7). As the mechanism for the deposition of pigment within the bronchus and fibrosis associated with tuberculosis, there is a theory that inflammation in the tubercular lymph nodes induces tuberculosis in the endobronchus through the bronchial wall, resulting in pigment deposition and stenosis (8). Reports about anthracosis and tuberculosis are not rare; however the relation between endobronchial tuberculosis and anthracosis is not frequently reported. The typical characteristics of patients with bronchial stenosis due to anthracofibrosis are elderly women, without a prior history of pneumoconiosis or smoking, a chief complaint of cough without systemic symptoms or dyspnea and findings of segmental or lobar consolidation on the plain chest radiographs. In addition, chest computed tomography reveals diverse bronchial abnormalities surrounded by soft tissue or lymph nodes. The most commonly involved area is the right middle lobe bronchus and an active tuberculosis infection is demonstrated in more than 60% of the patients which concur with the present findings (9).

All suspected patients of endobronchial TB should be subjected to sputum smear and culture examination for M. tuberculosis. Test results of sputum smear for AFB are not satisfactory for parenchymal involvement even in an optimal laboratory setup with meticulous sputum examination. In recent studies, sputum positivity in EBTB has been demonstrated from 16 to 53.3 % (9-11).

Bronchoscopic biopsy should be performed for all cases with anthracofibrosis. The biopsy specimen should be evaluated for AFB and the specimen should also be cultivated. Our case demonstrated the possible correlation between anthracofibrosis and endobronchial TB. We showed this correlation visually and microbiologically. Endobronchial lesions were disappeared at the 6th month of the TB treatment. Visualisation of the improvement with treatment of TB makes our report valuable to show this correlation.

In conclusion, bronchial anthracofibrosis should be suspected in older, non-smoking women exposed to biomass combustion products whose clinical and radiographic features are suggestive. Sputum should be evaluated for acid-fast bacilli smear and culture, and if this test result is negative for tuberculosis, bronchoscopic investigation should be done to exclude diagnosis of TB due to common association of TB and anthracosis.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

References

1. Chung MP, Lee KS, Han J, Kim H. et al. Bronchial stenosis due to anthracofibrosis. Chest. 1998;113:344-350

2. Kim HY, Im JG, Goo JM, Kim JY. et al. Bronchial anthracofibrosis (inflammatory bronchial stenosis with anthracotic pigmentation). AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;174:523-527

3. Kumar V. Robbins and Cotran Pathologic basis of disease; 7th ed. Elsevier. 2004

4. Long R, Wong E, Barrie J. Bronchial anthracofibrosis and tuberculosis: CT features before and after treatment. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184:S33-S36

5. Hoheisel G, Chan BK, Chan CH. et al. Endobronchial tuberculosis: Diagnostic features and therapeutic outcome. Respir Med. 1994;88:593-597

6. Han JK, Im JG, Park JH. et al. Bronchial stenosis due to endobronchial tuberculosis: Successful treatment with self-expanding metallic stent. Am J Roentgenol. 1992;159:971-972

7. Torun T, Gungor G, Ozmen I. et al. Bronchial Anthracostenosis in Patients Exposed to Biomass Smoke. Turkish Resp J. 2007;8:48-51

8. Abraham GC. Atelectasis of the right middle lobe resulting from perforation of tuberculus lymph nodes into bronchi in adults. Ann Intern Med. 1951;35:820-835

9. Aggarwal AN, Gupta D, Joshi K, Behera D. et al. Endobronchial involvement in tuberculosis: A report of 24 cases diagnosed by fibreoptic bronchoscopy. J Bronchol. 1999;6:247-250

10. Chung HS, Lee JH. Bronchoscopic assessment of the evolution of endobronchial tuberculosis. Chest. 2000;117:385-392

11. Yu W, Rong Z. Clinical analysis of 90 cases with endobronchial tuberculosis. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi. 1999;22:396-398

Author contact

![]() Corresponding author: Taha Tahir Bekci, MD. Address: Konya Education and Research Hospital, Meram 42090 Konya/Turkey. Phone:+ 90 533 3787676 E-mail: doktortahagov.tr

Corresponding author: Taha Tahir Bekci, MD. Address: Konya Education and Research Hospital, Meram 42090 Konya/Turkey. Phone:+ 90 533 3787676 E-mail: doktortahagov.tr

Global reach, higher impact

Global reach, higher impact